Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

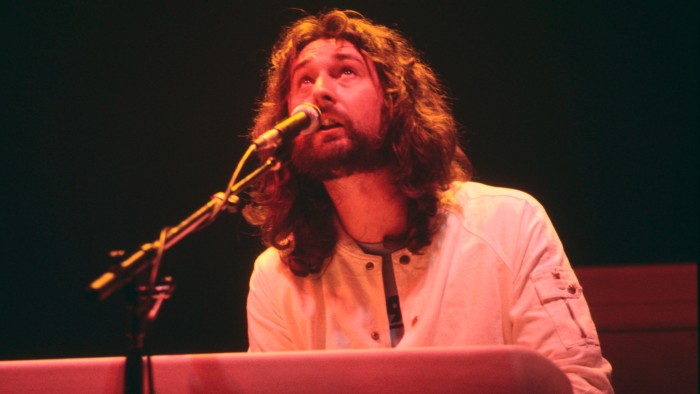

Supertramp’s Rick Davies was “taciturn” and “an introvert”, according to interviewers in the 1970s, with “stern deadpan features”. More patient interlocutors were able to discern qualities that lay behind the keyboardist-singer’s guarded manner, finding “a soft-spoken and insightful fellow” with a dry wit. These were unheroic characteristics in an age of grandiloquent musical gestures — but they underpinned his band’s self-dubbed “sophisto-rock”.

Davies, who has died aged 81 in the US, was born and grew up in the Wiltshire town of Swindon, a byword for English ordinariness. His father was a merchant seaman who died in 1973, when Davies was struggling to establish Supertramp. His mother was a hairdresser who ran a salon until 1979, when her son’s band released their landmark album Breakfast in America. It topped charts on both sides of the Atlantic and sold an estimated 20mn copies.

Davies’s imagination was captured by music from a young age. Initially attracted to drumming, he taught himself to play keyboards. Stints in bands were interspersed with work as a welder, which he detested. Vital financial backing came in 1968 when he was taken up by a patron while working in Europe with a British band, gigging at night and recording low-budget German film soundtracks by day.

Dutch millionaire Stanley August Miesegaes, known as Sam, was convinced by Davies’s fledgling songwriting talent. “Of course, all sorts of crazy ideas popped up from Sam, like ‘Rick Around the World in 80 Tunes’ whereby we’d hire a few Land Rovers and go round the world,” Davies recalled in 1975.

One of Sam’s not-so-crazy ideas was for his protégé to form a new band in London in 1969. Initially (and unpromisingly) named Daddy, they became Supertramp the following year. The name was taken from an autobiographical book by the vagrant Welsh poet WH Davies (no relation). The original line-up included another keyboard-playing singer, Roger Hodgson, who would become both Davies’s songwriting foil and his antithesis.

Supertramp’s first two albums were undistinguished efforts at progressive rock. Line-up convulsions left Davies and Hodgson as the only remaining founders. Sam’s support ended, but their label stuck with them. New recruits led to the quintet that made their key records over the next decade.

Crime of the Century was their breakthrough in 1974. Songwriting and lead vocals were shared between Davies and Hodgson. The latter devised the album’s hit single “Dreamer”, a harmonically lush number about escapism, while Davies wrote and sang bluesier tracks such as “Bloody Well Right”, about life’s vicissitudes. The difference summed up the two men’s opposing temperaments.

In contrast to Davies’s working-class upbringing, Hodgson was from a well-off family. He was educated at Stowe, the elite private school. He was a dreamer; Davies, a sardonic realist, did not share his enthusiasm for yoga, vegetarianism and spirituality. At gigs, he would wear a suit while Hodgson sported a kaftan and jeans. Davies’s vocals were grainier.

The pair’s friction found a delicate equilibrium in Supertramp’s “sophisto-rock”, combining the melodic songcraft of classic British pop with intricate arrangements and art-rock experimentalism. They toured with a sound system reportedly costing $250,000.

Supertramp’s apogee came with Breakfast in America, which followed Davies and Hodgson’s relocations to the US. The songs had a polish and vibrancy that anticipated the soundworld of the 1980s. The former prog rockers had become pointers towards what would become known as yacht rock. (Diana, Princess of Wales, was a fan.)

The album’s multi-platinum sales gave Supertramp a brief but plausible claim to be the world’s biggest band. Hodgson wrote the big hits including “The Logical Song”. Davies was responsible for deep cuts such as “Casual Conversations”, inspired by his growing estrangement from his bandmate.

They released one more album together, 1982’s fatefully titled Famous Last Words, after which Hodgson quit Supertramp, leaving Davies as leader. Ahead lay the path of break-ups, reunions and royalty disputes commonly experienced by successful groups in their declining years. His wife, Sue, whom he married in 1977, was the band’s manager from 1984.

Davies was diagnosed with cancer in the 2010s, an illness that brought out his stoical character — another quality that the 1970s music press failed to apprehend in a musician who didn’t conform to rock cliché.