Archaeologists in Scandinavia are showing how new advances in artificial intelligence and free game development software could change how the public encounters the distant past. In a new study published in Advances in Archaeological Practice, researchers from the University of Copenhagen and the University of Bergen demonstrate that historically grounded interactive video games can be produced quickly and inexpensively, without advanced technical training.

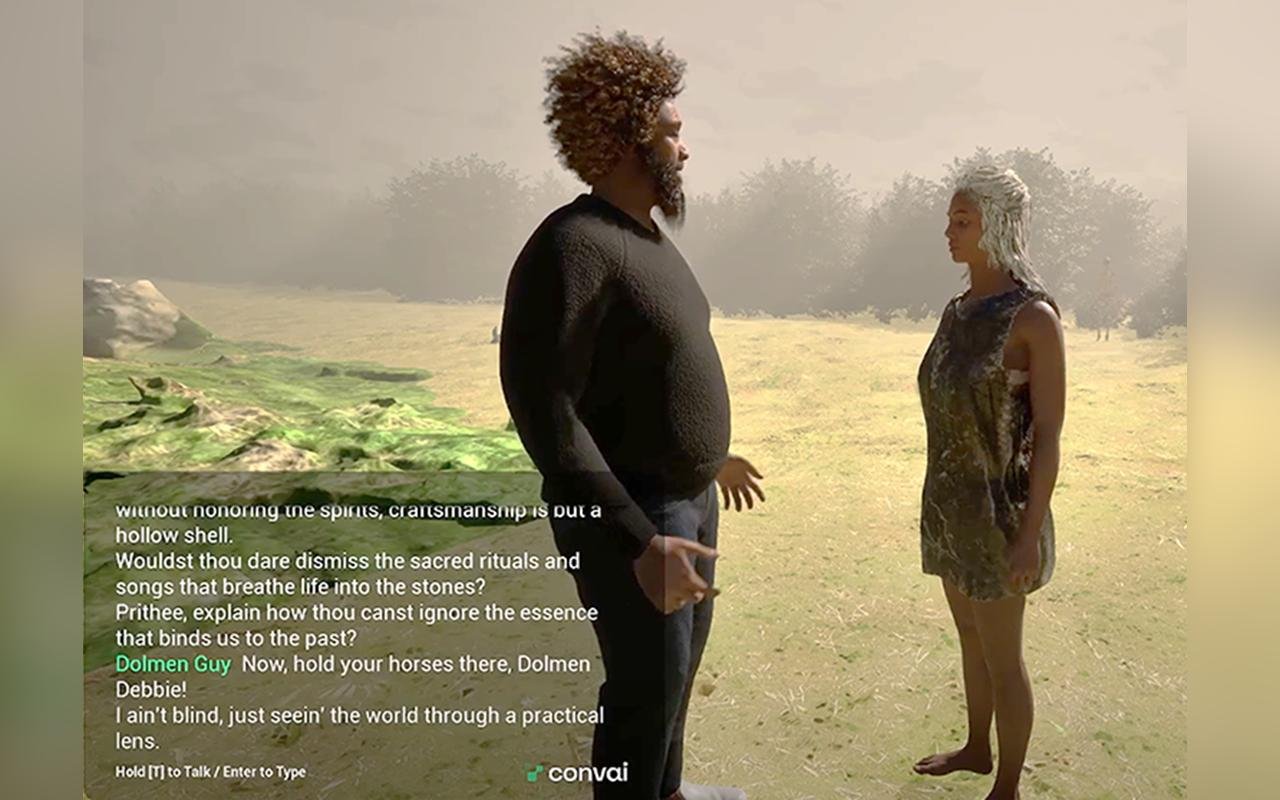

Gameplay featuring two NPCs engaged in a heated discussion about how Neolithic dolmens were built, by Mikkel Nørtoft. Watch on Nørtoft’s YouTube channel. Credit Nørtoft, M., Hofmann, D., & Iversen, R. Advances in Archaeological Practice (2025)

Gameplay featuring two NPCs engaged in a heated discussion about how Neolithic dolmens were built, by Mikkel Nørtoft. Watch on Nørtoft’s YouTube channel. Credit Nørtoft, M., Hofmann, D., & Iversen, R. Advances in Archaeological Practice (2025)

For the past several decades, museums and educators have relied on videos, static displays, and carefully scripted multimedia for educational purposes concerning archaeological sites. Truly immersive digital experiences, however, have largely remained the domain of large commercial studios. History-based games that have reached global audiences were less focused on historical facts and did not allow researchers to update content as new discoveries emerge.

However, the new research combines free software like Unreal Engine with AI-powered conversational tools and publicly available tutorials to create a simple but complex 3D game centered on the Neolithic period in Northern Europe. Such a project can be considered a proof-of-concept demonstration that archaeologists themselves can develop interactive “archaeogames” for teaching and heritage communication.

The simulation is based on real archaeological data. The basic setting is modeled using three-dimensional scans taken at well-preserved Neolithic long dolmens at Lindeskov Hestehave in Denmark. Players explore a forest clearing and interact with two digital characters: an archaeologist and a prehistoric woman. Unlike most other games of this genre, these two characters use guarded generative AI to engage in open-ended conversation, drawing on curated archaeological knowledge. This allows dialogue to feel natural while remaining academically grounded.

Because the characters are not tied to pre-written dialogue trees, the game can be updated as new interpretations emerge. Later on, the researchers added an extra level with animal characters, open landscapes, and a cave with a shaman character, introducing prehistoric rock art. Early testing with players from different backgrounds showed that the format is engaging and accessible even for those without prior knowledge of archaeology.

The study also highlights broader implications for cultural heritage. Some tools, originally developed for documentation, such as 3D photogrammetry, now have the potential to be repurposed to create interactive learning environments. Museums and educators could utilize these games in educational or exhibition settings, or even share them online to reach wider audiences.

The authors also note some potential risks. With improved usability of game-building tools, historically themed content may increasingly be produced without a focus on historical accuracy. This increases the need for heritage professionals to take an active role in shaping this emerging space and offer people an engaging, evidence-grounded experience.

Publication: Nørtoft, M., Hofmann, D., & Iversen, R. (2025). Gamifying the past: Embodied LLMs in DIY archaeological video games. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 1–17. doi:10.1017/aap.2025.10106