“Marriage seems a revolting institution, unless the parties have enough money to keep reasonably distant from each other,” a 21-year-old Philip Larkin wrote to his friend Kingsley Amis in 1943.

This aversion to matrimony continued throughout Larkin’s life, and instead, he found companionship in his long-term and overlapping relationships with the lecturer Monica Jones and his colleague, Maeve Brennan. They are both buried close to him in Cottingham cemetery near his adopted home city of Hull.

But he did also find something akin to his youthful ideal of a low-maintenance marriage with a lesser-known “third woman”, his longtime secretary — and latterly lover — Betty Mackereth.

“As he had no wife to confide in, I felt that I took that place,” she later recalled, though there was never any desire on her part to make their relationship more official. “I would never have wanted to marry him. I think I knew him too well.”

In many ways, she knew the moody poet and librarian better than a wife could have done. He needed to pass through her office every day to reach his, and she soon learnt to judge whether he would spend the morning “staring at the picture that he’d borrowed from the fine art collection on the other side of his room”.

He was also deeply emotional, and on one of his low days, Mackereth found him standing in front of the window with tears streaming down his face because he had accidentally killed a hedgehog that lived in his garden — an incident he wrote about in his poem The Mower.

Thoughts of mortality haunted Larkin, and he once said to Mackereth: “I cannot understand why you, on waking in the morning, don’t think of death.” Her reply: “I cannot understand why you, on waking in the morning, think of death.”

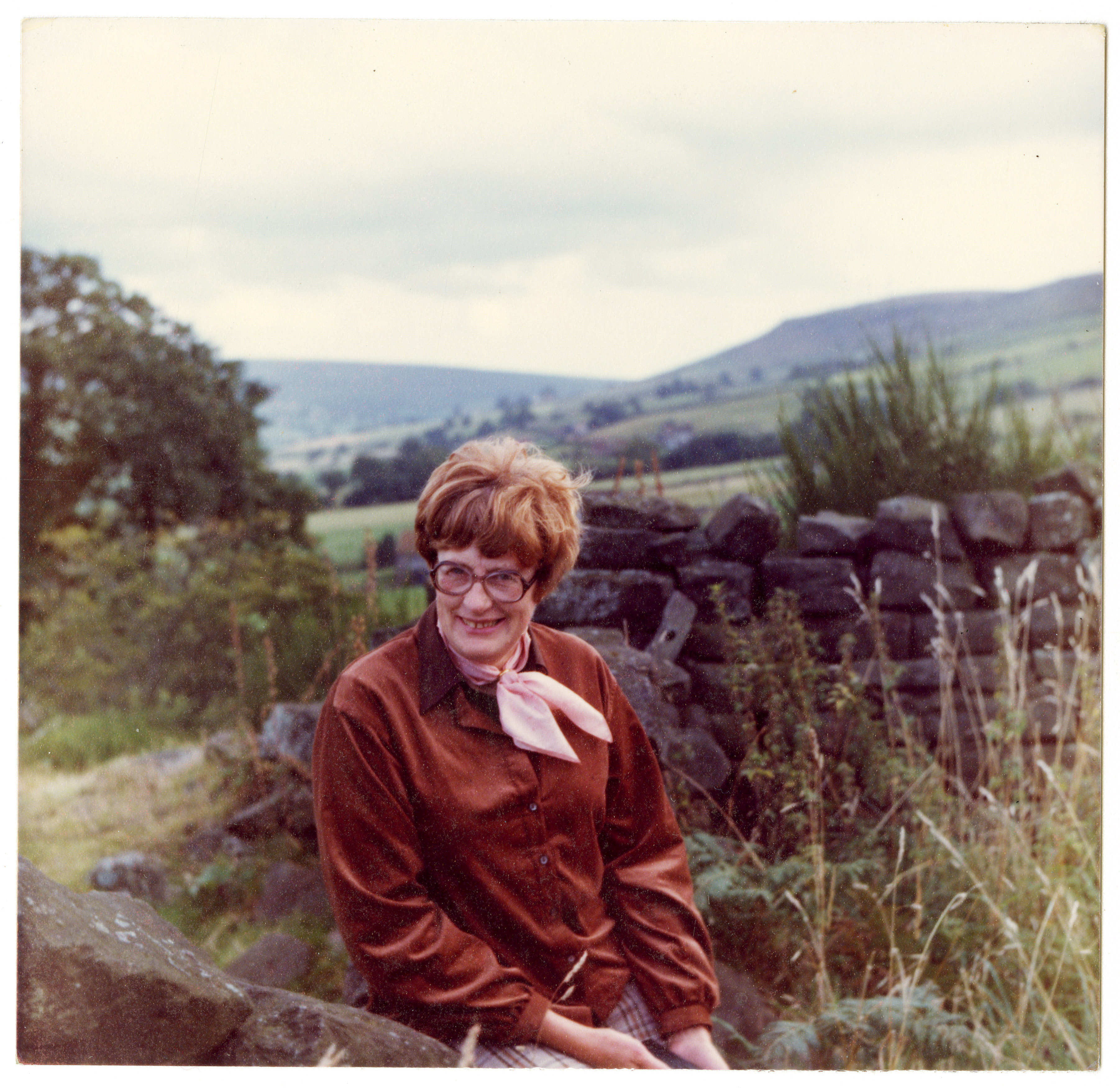

Mackereth in 1981

PHILIP LARKIN ARCHIVE/COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY OF AUTHORS

In contrast, Mackereth was an active and upbeat figure. She played bridge, golf and badminton, and her efforts were a source of amusement for Larkin. In one letter to a friend who played golf, he wrote: “I think I said my loaf-haired secretary had taken up the game and thrashes about manfully or womanfully.”

He immortalised this nickname in his 1962 poem Toads Revisited, with the phrase “give me my in-tray, my loaf-haired secretary” in apparent relief at the familiarity and structure of his work at the library. This gives a rather more positive outlook than his earlier poem Toads, where he describes work as something that: “Six days of the week it soils/ With its sickening poison.”

Larkin also confided in his secretary about his entanglements with Brennan and Jones, and when she was later asked about his complicated romantic life, she said: “It seems quite natural for men to do that sort of thing. He was one of the pioneers.”

However well Mackereth knew him, Larkin’s eventual romantic interest in her came as a complete shock. She had already been working as his secretary at the University of Hull library for 17 years when their affair began, while they were both in their fifties.

Having planned his approach carefully, Larkin drove Mackereth home from a work event via a circuitous route so that he could drop off his other passenger first. When he eventually pulled up outside her house, he asked: “Aren’t you going to invite me in for coffee?” She did so, and he broke a saucer, and “one thing led to another”.

Betty Mackereth was born in Hull in 1924 and later went to Newland High School. She was sent to a government training facility in Leeds during the Second World War, where she was a quality-control inspector and learnt how to weld.

She returned to Hull for a job in the Transport Department in 1945 and then obtained the role of Larkin’s secretary at the University of Hull’s Brynmor Jones Library in May 1957. Soon after, Larkin wrote to his mother Eva: “My new secretary has begun and seems alright in a way … she will probably stay all her life now.”

Mackereth’s first appraisals of Larkin and his library were even less effusive. She was “staggered” by how little work everybody appeared to do and recalled thinking: “What an awful place to come to.”

She made light work of her to-do list, and in the end, Larkin became so fed up of her asking for more work that he went to the Institute of Education across the road, picked up a book they did not hold in the library, and asked her to copy it word for word so he could have it bound and put on their shelves. “That kept me quiet.”

But when they moved to a new building in 1969, they established a better footing, and in another letter sent to his mother that year, Larkin wrote: “My mainstay is Betty, boundless energy, always cheerful and tolerant, and if she doesn’t do half my work she sort of chews it up to make it easier for me to swallow. I’d be lost without her.”

As Larkin started to develop a level of fame, he told Mackereth that the only people she should put through to him on the phone were the Palace, Downing Street, the university’s vice-chancellor and the chairman of the library committee. He gifted her a toy alligator that she kept long after his death, to symbolise how “you keep everyone at bay”.

She insisted their working relationship did not change after their affair began in 1976, saying only that “he was a very good boss”. As Larkin had predicted, she remained his secretary until she retired in 1984, and they saw each other regularly until he died, aged 63, the following year.

Upon his death — and with the approval of Jones, who by then knew about their relationship — she fed Larkin’s diaries into the library shredder page by page as per his instructions and sent the remainder to the university incinerator. She insisted she “never read a word”, adding: “I only know that Philip would have been very honest with his diaries.”

Mackereth had promised Larkin that she would “not tell a soul” about the true nature of their relationship, and for some time after his death she managed to keep their affair — and the hundreds of letters he had written to her — a secret.

His letters were often illustrated with a whale (his pet name for her) and contained a series of poems addressed to her, including Morning at Last: There in the Snow; We Met at The End of the Party; When We First Faced, And Touching Showed; and Dear Jake.

Some of these “old age” poems existed only in his letters, but there were enough fragments in the public domain for Larkin’s friend and biographer, Sir Andrew Motion, to identify Mackereth as a secret lover. He asked her outright and exposed the affair in his 1993 book Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, which she did not take to kindly, and she refused to show him the poems.

Almost ten years later, Mackereth released We Met At The End of The Party when an earlier draft was unearthed in a notebook found after Larkin’s home in Newland Park was cleared and the furniture taken to a tip. A Guardian report implied the first verse of the poem was doggerel and unlikely to be by Larkin, so she broke her silence to set the record straight and allowed the finished poem to be circulated among the 300 members of the Philip Larkin Society in their newsletter.

In 2010, Motion went back with “a degree of trepidation” to see an 87-year-old Mackereth for his documentary Philip Larkin and the Third Woman. Recalling how he had confronted her, she told him: “I didn’t like you. I’ve never liked you since”. Larkin had chosen his crocodile well, but she did finally give Motion access to her letters.

On seeing the full series of poems written to Mackereth in the documentary, the Larkin expert Professor James Booth said: “She appears to him, in my view, as a muse of vitality and longevity, with a genuine emotional kick.”

The poems included the previously unseen Dear Jake, which refers to the “four lives fractured by affection” that made up his tangled sexual affairs. But Mackereth left it a little longer to clear up speculation about which woman he had truly loved.

It was not until an appearance on the 2017 documentary Through The Lens of Larkin that she revealed the poet had told her on his deathbed: “Maeve came to see me, I didn’t want to see Maeve, I wanted to see Monica to tell her that I loved her.”

Asked about her own feelings for the poet, she said: “It’s difficult to explain. I did love him in a way. I wasn’t in love, but I did love him as a person.”

Mackereth carried the vitality Larkin had so admired into old age, celebrating her centenary with cake and a letter from the King at Red Stacks Residential Home in Hessle, where she had plenty of visitors and told a local newspaper that the secret to a long life was “enjoying your food”.

Unlike Larkin, her aversion to marriage was circumstantial rather than on principle. She said: “I was the kind of person who didn’t find the right man. I didn’t want to marry just for the sake of being married. I’m waiting for the next life to meet my soulmate.”

Betty Mackereth, Philip Larkin’s secretary and lover, was born on June 27, 1924. She died on November 20, 2025, aged 101