Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

If one is interested in the electrification of developing countries, Bolivia is perhaps the most interesting Latin American country to follow in 2025. Amidst a two-year-long fuel crisis, the Andean country has been quietly building a massive EV revolution as ICEV sales slowly collapse, as we reported earlier this year.

Which makes it all the more frustrating that I cannot find reliable data on how sales in the country look.

Regardless, through the last few weeks, I’ve been trying to get as much information as possible to at least present a general picture. However, because I know our CleanTechnica readers like to be further informed, I’ll present some brief context on how Bolivia got to this place before showing the available data we have about what’s going on.

Brief history of Bolivia

Historically, Bolivia had been known as “High Peru” — due to the high Andean peaks and plateaus from the Viceroyalty of Peru. After Independence, the two countries briefly toyed with unity, but the experiment was over already by 1839.

As the core of the former indigenous lands under Incaic rule, Bolivia remains a country with a very large proportion of indigenous population, somewhere between 38% and 48% according to multiple sources. Despite this, for decades the country remained under the rule of a largely urbanized, white(ish) political elite. Though, this by no means translated to overwhelming conservative politics, as parties such as the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR) remained relevant through the second half of the 20th century.

After a deep political crisis that led to several presidents resigning in series, Evo Morales won the national elections in 2005 and became Bolivia’s first indigenous president, and also the first president ever to win with an absolute majority (54%), hence not requiring a second electoral round. Evo went to reform the Constitution and became the first president of the (now renamed) Plurinational State of Bolivia, implementing big social policies that would be funded thanks to the commodity boom in those years. Evo was far from the only leftist leader in our region, and the overall success of the Latin American left in most countries at the beginning of the millenium (including Venezuela, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Brazil, Peru and Ecuador) went on to be called the “Pink Tide.” A lot of very prominent leftist policies, including the nationalization of fossil fuel resources (voted for in a Plebiscite in 2004) and the building of La Paz’s famous gondola system, come from these years.

Fuel subsidies amidst growing and then falling fossil fuel production

1997 was the first year (in recent history) when fuel prices were frozen as a means to control inflation. In 2004, the price went up, but it was once again frozen to keep it as a one-time thing. By then, there were nearly half a million ICEVs in Bolivia’s streets.

In 2010, Evo tried to raise the price (which was once again far below market prices), but popular opposition did not allow him to. At this point, Bolivia’s ICEV fleet had nearly doubled to 960,000 vehicles, meaning the cost for sustaining this subsidy had likely doubled as well.

But back then, the government had the resources to pay for it thanks to significant gas reserves, steady (if low) oil production, and the commodities boom. By 2014, Bolivia reached the highest level ever in fossil fuel production. Oil stood at just over 50,000 barrels a day (a very small amount by international standards, but probably enough to move a million vehicles), whereas gas was a much larger 59 million cubic meters a day.

However, as many of our readers may remember, that was the year that commodity prices crashed. As revenues fell, investments floundered and reserves dwindled, leading to stagnation and then secular decline, with production falling by around 50% through the next decade: in 2024, production had fallen to 32 million cubic meters a day for gas, and to 23 thousand barrels a day for oil.

And through this decline, Bolivia’s ICEV fleet kept rising, and fuel demand kept increasing. With shrinking production, the country was forced to import fuel in order to sell it at discount rates at a time when gas prices were also going down and thus exports were falling. As a result, the government — not wishing to spark social unrest — resorted to Bolivia’s international reserves, which had only recently been built up.

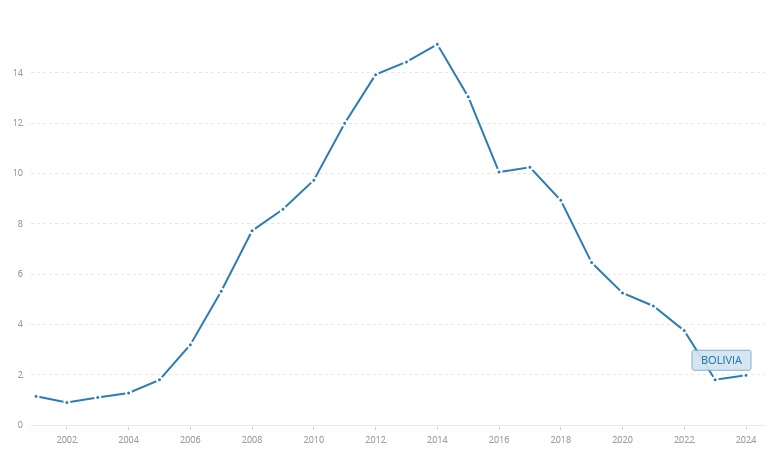

The result was catastrophic. Reserves had risen from a pittance in 2004 (1.1 billion USD) to a significant 15 billion in 2014, but by 2023 they were back down to 1.7 billion. At this point, it was clear that something had to change.

Bolivia’s International Reserves, as per the World Bank.

Bolivia’s International Reserves, as per the World Bank.

By 2024, Bolivia’s vehicle fleet had risen to over 2.5 million vehicles, though with a small presence now of EVs. Fuel had become scarce and lines had become common at gasoline stations. The economy stalled, with a 1.1% reduction that year, whereas the cost of gasoline subsidies rose over 2 million dollars, over 5% of its total budget, and only at the cost of decimating its reserves.

The end of the fuel subsidy

Long story short, significant infighting at the Socialist Alternative Movement, Evo Morales’ Party, plus the economic crisis, led to the victory of a center-right candidate in 2025’s elections: Rodrigo Paz Pereira.

President Paz declared Economic Emergency almost immediately, with the first decision being the raising of gasoline prices, almost doubling the previous ones. At $1 per liter for low-grade, $1.58 for premium, and $1.40 for diesel, prices are now more in line with the rest of the region. Though, they remain cheaper if we use the parallel exchange rate instead of the official one.

The decision sparked panic amongst vehicle owners, with long lines to buy the last available fuel at subsidized prices. Despite social unrest, it seems the scenario from 2010, with massive protests, has not been repeated. Paz also increased the minimum wage, aiming to “protect the wallets of Bolivians,” as the rise in fuel price will inevitably increase inflation.

It’s hard to predict whether this will affect EV sales positively or negatively. On one hand, fuel will now be more expensive, but on the other, it’s likely that it will now be available at all moments, providing certainty to vehicle owners that they’ll be able to refuel. Regardless, two years of systematic fuel scarcity probably have changed the mindset of a lot of Bolivians.

What do we know about EV adoption in Bolivia?

This brings us to the latest part of our article: how many EVs are being sold in Bolivia? I’ve made a significant effort to get this data, but, sadly, it remains outside our scope. But what we did find was data on locally available models, and import numbers, and that ought to give us a general idea on what’s happening there.

Regarding models, aside from the local brand Quantum, it seems BYD and JMEV are the main EV brands currently present in Bolivia. I’ve found it very hard to compare prices for EVs and ICEVs, as for whatever reason, EVs tend to appear in Bolivianos whereas ICEVs are offered in US dollars: the JMEV EV3, for example, could be either 50% more expensive than the Renault Kwid or similar in cost, depending on whether we use the official exchange rate or the parallel one. It’s been a common talking point that EVs are far more expensive than ICEVs, but after comparing a couple of models, I’m not too convinced. There’s significant presence of Chinese brands in the country, but for now most of these brands are focused on the ICEVs of yore. Though, Geely already has an upcoming section for three of its EVs (probably the Geome, the EX5, and the PHEV Starray EM-i).

Regarding imports, Bolivian media reports that the cost of EVs entering the country has grown exponentially: in 2022, 1.8 million USD were spent on bringing in such vehicles, with the number rising to 3.74 million in 2023, 4.98 million in 2024, and an astonishing 16.3 million in Jan–Oct 2025. This represents 300% growth over 2024, and since EVs are likely to be cheaper the more recently they were imported, it’s also likely the number of imported units was higher.

We also found that total imports for “transportation equipment” for 2025 (Jan–Oct) was 203 million dollars, meaning EVs accounted for 8% of that value. But if we account for the fact that not all that transportation equipment was vehicles, EV sales probably account for a higher percentage than that.

And it gets better. There’s the Bolivian homegrown EV company: Quantum, specialized in selling mini-cars and motorcycles — though, they now have at least one city-car directly competing with Chinese imports, several last-mile delivery trucks, and one mid-range, 2-ton, fast-charging capable truck. In all fairness, I couldn’t determine if all these heavier vehicles are locally built, are locally assembled, or are imported whole. But at least some of the sales certainly go to locally buily mini cars from Quantum, meaning market share should be higher than imports indicate.

The Quantum Ion Pro seems like a surprisingly competitive mini-truck, though I couldn’t make sure it’s built in Bolivia. It starts at $28.000 or $40.000 depending on the exchange rate you use (parallel vs official).

The Quantum Ion Pro seems like a surprisingly competitive mini-truck, though I couldn’t make sure it’s built in Bolivia. It starts at $28.000 or $40.000 depending on the exchange rate you use (parallel vs official).

How high is EV market share then? I’d go with “at least 10%.” For now, that should be good enough, and it would place Bolivia in third place in the region, behind Uruguay and Costa Rica, and slightly ahead of Colombia (which reached 9.98% in November).

Final thoughts

Bolivia wasn’t alone in its decision to end fuel subsidies: Ecuador also did so with gasoline in 2024 and with diesel this past September, and Venezuela has limited the amount of subsidized gasoline per citizen. In all cases, social unrest (when and where it happened) was not enough to deter either government, marking a stark difference with prior efforts.

A part of this, of course, is a result of economic crisis and/or stagnation. That probably has hammered into the conscience of parts of the population that fuel users need to pay the full price if the state is to remain viable. But a part of me wonders if the presence of EVs as a rising force in Bolivia and Ecuador has also made a difference. Years ago, gasoline was a fundamental need; nowadays, it’s a choice, one that may provide reliability or comfort, but that is by no means required for people or companies to get by. In the case of Bolivia, I’d gather this effect would be further compounded due to the existence of a local EV champion.

I don’t know a lot of people in either country (actually, I don’t know anyone in Bolivia), so it’s hard for me to answer this question. And even if EVs have indeed influenced this result, I’d expect it would be in a mostly silent, perhaps unconscious way. But the fact remains that now one can finally live, work, and thrive without gasoline, and do so while supporting the local economy, and, in the case of Bolivia, the national industry. And that has got to make a difference.

What do you guys think?

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Advertisement

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.