A new study published has demonstrated that reducing background brain activity can sharpen attention, identifying the Homer1 gene as key to developing new targeted treatments for ADHD and related disorders.

Attention disorders such as ADHD are often described as a failure to separate signal from noise. The brain is continually flooded with sensory information, and the ability to focus relies on filtering out distractions while responding to what matters. Most existing treatments work by stimulating brain circuits involved in attention. Now, new research suggests turning down background neural noise could be the key.

In a new study, researchers from the Rockefeller University report that the gene Homer1 plays a central role in shaping attention by regulating baseline brain activity. Experiments in mice showed that lower levels of two specific versions of the gene were linked to quieter neural activity and significantly improved focus. The findings could open new therapeutic directions for ADHD and other conditions associated with early sensory disturbances, including autism and schizophrenia.

“The gene we found has a striking effect on attention and is relevant to humans,” says Priya Rajasethupathy, head of the Skoler Horbach Family Laboratory of Neural Dynamics and Cognition at Rockefeller.

An unexpected genetic player

Homer1 was not an obvious candidate when the researchers began exploring the genetics of attention. Although the gene is well known for its role in neurotransmission, and many of its interacting proteins have appeared in human genetic studies of attention disorders, Homer1 itself had not previously been implicated so directly.

Homer1 was not an obvious candidate when the researchers began exploring the genetics of attention.

To address this, the team analysed the genomes of nearly 200 mice bred from eight diverse parental lines, including some with wild ancestry. This approach was designed to reflect the genetic diversity seen in humans and to reveal genetic effects that might otherwise remain hidden.

The analysis revealed that mice with the strongest attention performance had much lower levels of Homer1 in the prefrontal cortex, a key brain region for focus and decision-making. The gene lay within a genetic region that explained almost 20 percent of variation in attention across the mice. “Even accounting for any overestimation here of the size of this effect, which can happen for many reasons, that’s a remarkable number,” Rajasethupathy says. “Most of the time, you’re lucky if you find a gene that affects even one percent of a trait.”

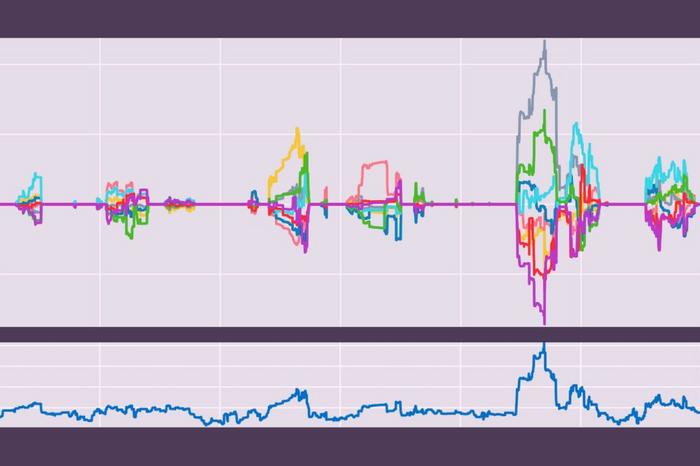

A quantitative trait locus graph showing that the Homer1 gene region is associated with behavioural divergence in attention. Credit: Rajasethupathy lab/The Rockefeller University.

Timing matters in brain development

Further investigation showed that the effect was driven specifically by two splice variants of the gene, known as Homer1a and Ania3. High-performing mice naturally had lower levels of these variants in the prefrontal cortex. When researchers experimentally reduced these variants during a narrow window in adolescence, the mice became faster, more accurate and less distractible across several tests. The same intervention in adulthood had no effect, highlighting a critical developmental period.

The most surprising finding emerged when the team examined how Homer1 influences brain activity.

The most surprising finding emerged when the team examined how Homer1 influences brain activity. Reducing the gene increased the number of GABA receptors in prefrontal neurons, effectively strengthening the brain’s inhibitory “brakes”. This produced a quieter baseline state and more precise bursts of activity when relevant cues appeared.

“We were sure that the more attentive mice would have more activity in the prefrontal cortex, not less,” Rajasethupathy says. “But it made some sense. Attention is, in part, about blocking everything else out.”

Towards calmer treatments for ADHD

For Gershon, who lives with ADHD, the findings resonated on a personal level. “It’s part of my story,” he says, “and one of the inspirations for me wanting to apply genetic mapping to attention.” He was the first in the lab to recognise that improved focus was coming from reduced distraction rather than heightened stimulation. “Deep breathing, mindfulness, meditation, calming the nervous system – people consistently report better focus following these activities,” he says.

Current ADHD medications boost excitatory signals in the brain. By contrast, this research points towards a potential new class of treatments designed to calm neural activity instead. Future work will explore how Homer1 might be targeted therapeutically.

“There is a splice site in Homer1 that can be pharmacologically targeted, which may be an ideal way to help dial the knob on brain signal-to-noise levels,” Rajasethupathy says. “This offers a tangible path toward creating a medication that has a similar quieting effect as meditation.”