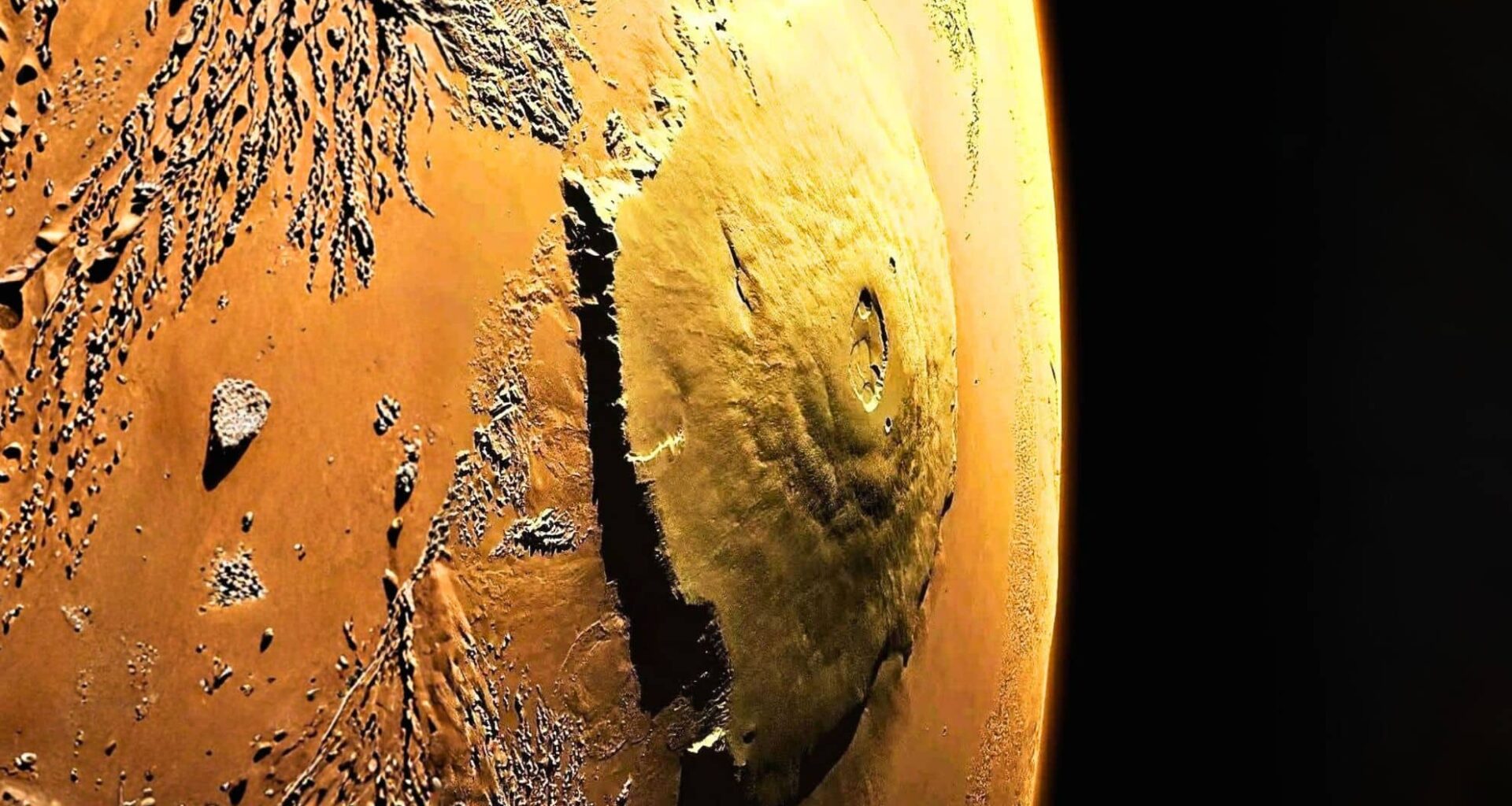

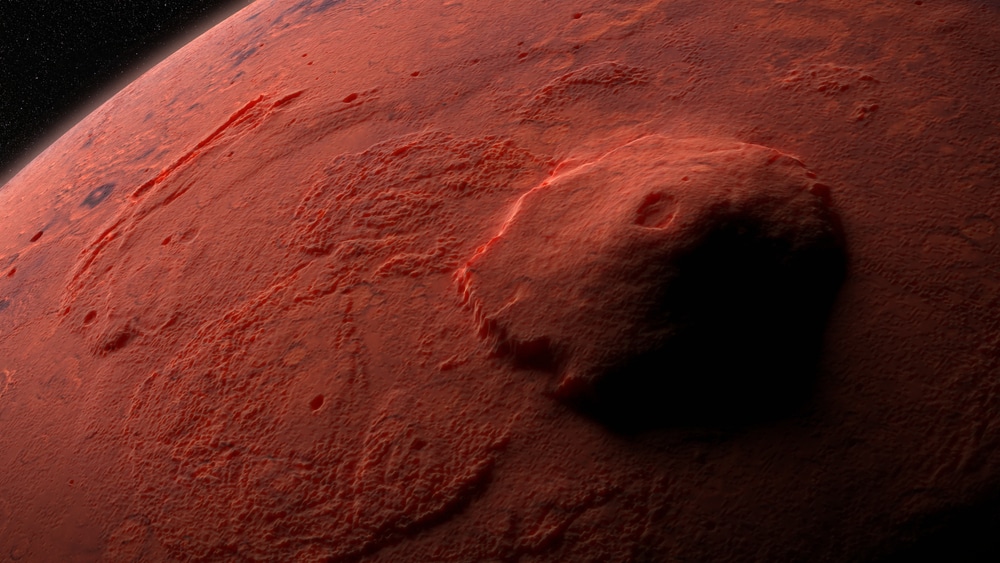

At the western edge of Mars’s equatorial highlands, an enormous geological structure rises far above the planet’s thin atmosphere. It has no counterpart on Earth, no active twin elsewhere in the solar system. For decades, it has stood as a symbol of planetary extremes—vast, still, and largely undisturbed.

From orbit, it appears less like a mountain and more like a shield stretched across the Martian surface. In high-resolution images, its summit seems surprisingly flat, its flanks unusually smooth. It casts no dramatic shadow and offers little visible evidence of recent change. Yet this apparent quiet conceals a complex and still-unfolding geological history.

Only recently have planetary scientists begun to map its interior with precision. Increasingly detailed imaging and elevation models are bringing into focus a deeper story—one that challenges long-standing assumptions about Mars, and the processes that shaped it. The structure’s origin, scale, and condition continue to raise questions that reach beyond Martian geology.

Its name is Olympus Mons. And while it is often defined by its size, what it may still reveal about planetary behaviour in the absence of tectonic motion is becoming the more compelling measure.

A mountain that breaks planetary records

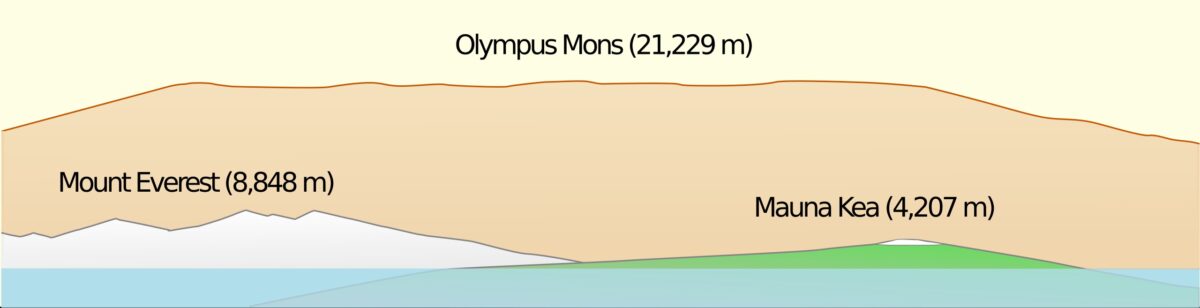

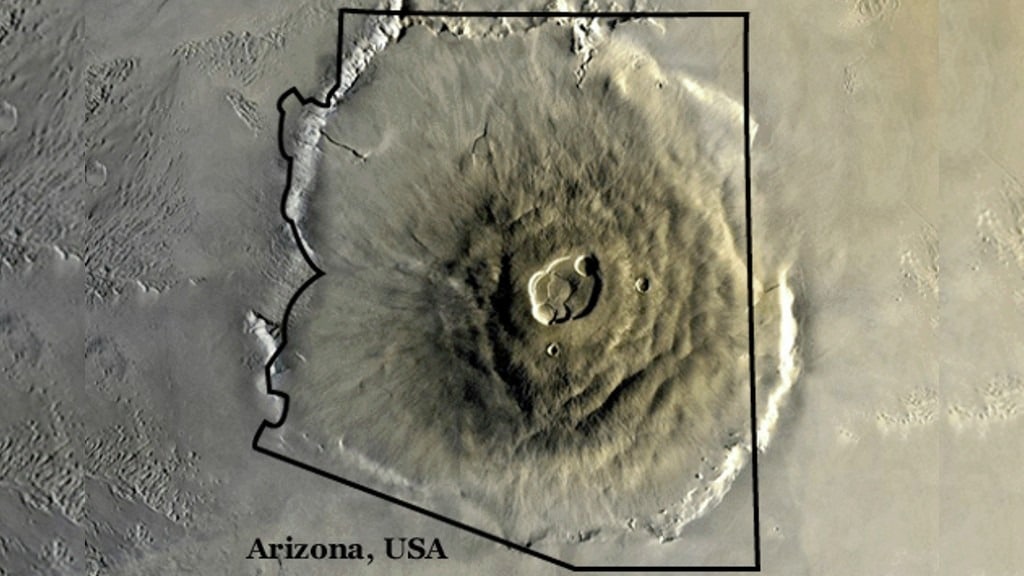

Olympus Mons is the tallest known volcano in the solar system. Rising to approximately 26 kilometres above the surrounding Martian plains, it exceeds the height of Mount Everest by nearly a factor of three. Its base spans more than 600 kilometres, covering an area larger than Poland.

This scale has long been recognised. However, recent observations by missions such as Mars Express and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have helped clarify how the volcano achieved its extraordinary dimensions. Its formation has been linked directly to the absence of plate tectonics on Mars.

Unlike Earth, where crustal plates move across the surface, redistributing volcanic activity over time, Mars has a static crust. Olympus Mons formed in a fixed location, above a stable magma source. Lava accumulated over millions of years, flowing outwards and upwards without being redirected by shifting plates. The result was not a chain of smaller peaks, but a single volcanic structure of exceptional size.

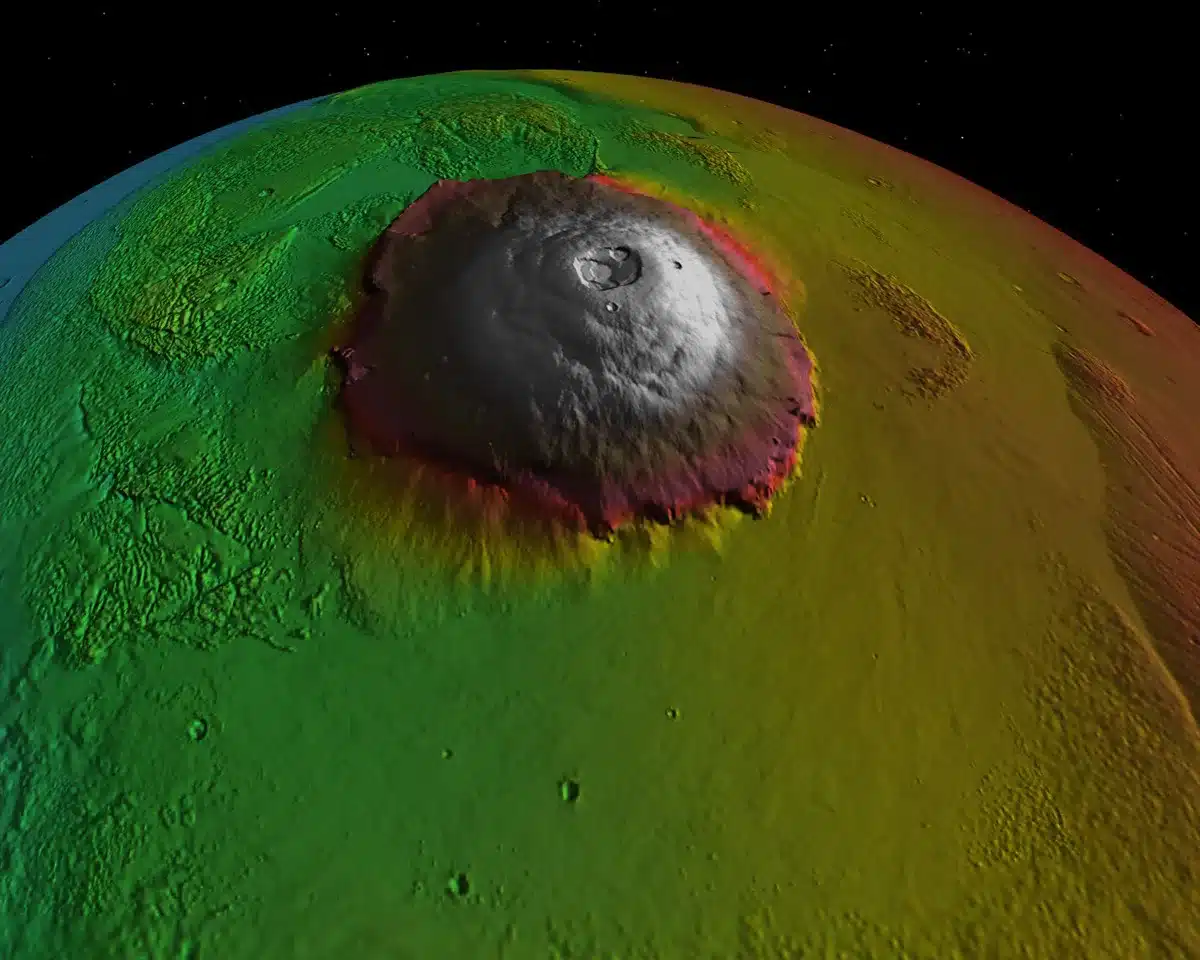

NASA elevation data also confirm the volcano’s unusually shallow slope—averaging only 5 percent. Because of this, an observer standing on its flanks might see little to indicate the mountain’s overall height. The summit would be beyond the horizon, masked by the mountain’s own gradual curvature.

Preserved by stillness and thin air

The volcano’s flanks are covered by smooth lava plains, channels, and terraces. Near the base, a steep escarpment—up to 6 kilometres high—drops into an annular depression, or moat. This feature is believed to have formed under the immense weight of the volcano pressing into the Martian crust.

At the summit, a cluster of six overlapping calderas—collapse features formed as magma chambers emptied—spans nearly 80 kilometres across. These structures suggest a complex and prolonged eruptive history. European Space Agency images show that some lava flows on Olympus Mons may be as recent as two million years.

Mars’s dry conditions and minimal atmospheric pressure have preserved many of these surface features. Without rainfall or sustained wind erosion, the mountain’s form remains largely intact. Evidence of past flows, collapses, and layering is unusually well preserved.

More recently, signs of frost and possible rock glaciers have been detected near the summit. ESA imagery shows lobed and ridged features that resemble glacial structures on Earth. These formations may contain water-ice preserved beneath debris and dust, potentially dating back only a few million years.

In 2024, Sky at Night Magazine reported frost deposits equivalent to roughly 60 Olympic swimming pools observed on the mountain’s upper slopes. Although not permanent, these seasonal features suggest interaction between Olympus Mons and the planet’s current atmospheric cycles.

A long volcanic lifespan

The duration of volcanic activity at Olympus Mons is another area of scientific interest. Crater-counting techniques suggest some surface layers are relatively recent. Other data point to an extended volcanic history, potentially exceeding two billion years.

A study from the University of Glasgow examined Martian meteorites known as nakhlites, believed to have formed in eruptions over a 90-million-year span. This type of longevity is uncommon on Earth, where volcanoes are typically active for only a few million years before extinction.

Lava flows analysed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show variation in age and composition. Some display well-defined lava channels bordered by hardened levees, suggesting slow-moving, basaltic eruptions. This eruption style allows for the gradual accumulation of mass without explosive events.

The surface of Olympus Mons is predominantly basaltic, rich in iron and magnesium. These volcanic rocks, formed from low-viscosity magma, explain the mountain’s expansive footprint and support theories about its long-term volcanic activity. A detailed Wikipedia analysis of the volcano’s mineralogy lists its surface as comprising roughly 44% silicates and over 17% iron oxides, contributing to Mars’s reddish hue.

Limits to access, but not to exploration

Despite its scientific value, Olympus Mons remains inaccessible to landers or rovers. The volcano’s high elevation means Mars’s already thin atmosphere becomes even less dense near the summit, limiting the effectiveness of parachute-assisted descents. The loose, dusty terrain adds to the challenge, complicating rover navigation and mechanical stability.

Even so, interest in Olympus Mons continues to grow in both public and academic circles. In 2021, a student team from the Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden proposed a human mission concept involving robotic ascent and partial human climbing, suggesting a feasible approach by 2042. The concept, called the Mount Olympus Mons Ascension Mission, outlines basic parameters for navigation and life support at high Martian altitudes.

Elsewhere, private-sector initiatives are focused on simulation. 4th Planet Logistics, a space design company, is developing a virtual climbing route based on publicly available topographic data. These projects aim to create immersive public experiences of Olympus Mons, while continuing to raise awareness of the volcano’s scientific value.

Orbital imaging missions remain the primary source of detailed geological data. High-resolution stereo cameras and spectrometers aboard Mars Express and MRO have provided surface maps and elevation models used to trace Olympus Mons’s growth, layering, and signs of continued activity.