In his lifetime, Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906) was an avid traveller, who ventured beyond the boundaries of his home state Kerala to observe his subjects from close quarters, and later set up an iconic printing press in Maharashtra. His paintings, especially those that were mass-produced as affordable prints by his press, enjoyed a pan-India appeal, beloved of the rich and poor alike. Ravi Varma’s afterlife has been no less eventful. Dismissed by artists like Nandalal Bose and historians like Ananda Coomaraswamy as a painter of kitsch, his reputation was revived by a major exhibition at New Delhi’s National Museum, curated by art expert Rupika Chawla and artist A. Ramachandran, in 1993.

The artist’s fortunes have been on the rise since then among elite patrons of galleries and auction houses. A Sotheby’s sale in New York in 2017 saw Ravi Varma’s untitled painting of the mythological heroine, Damayanti, fetch a whopping ₹11.09 crore, more than doubling the initial estimate. Historians and Ravi Varma enthusiasts (such as Lounge columnist Manu S. Pillai and lawyer turned-collector Ganesh V. Shivaswamy) have revived interest in the artist’s life and work among a new generation of Indians. And now Ravi Varma is poised to travel to Australia, thanks to a major show of his oleographs, organised by Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), which opens on 20 September in Brisbane.

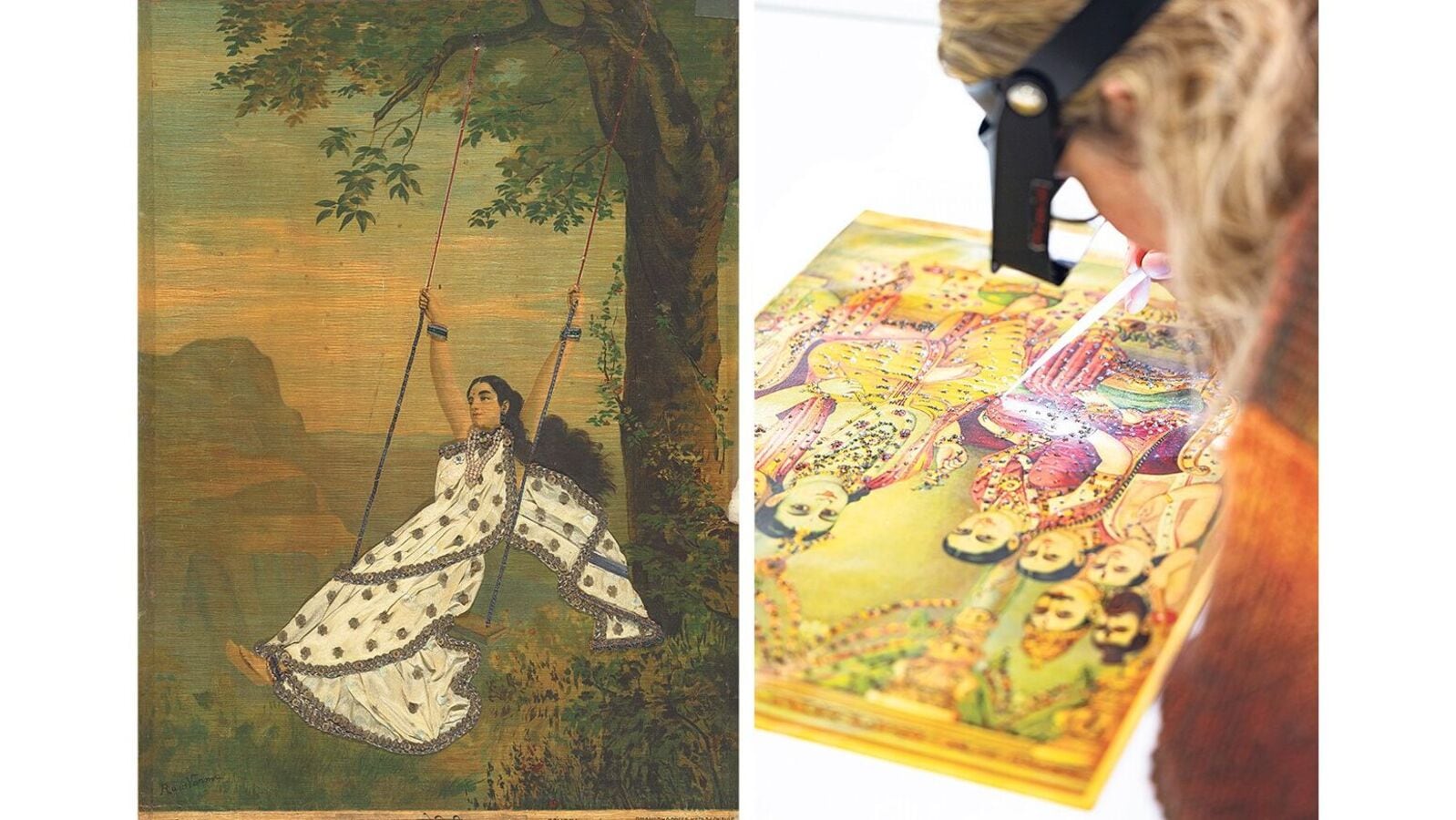

The collection, made up of 48 embroidered oleographs (which are essentially “lithographs with a coating of varnish designed to resemble oil paintings,” as conservator Kim Barett describes them), was acquired by QAGOMA from the Henry and Amanda Bartlett Trust in 2024. Currently a beneficiary of a Maitri grant, which is disbursed by the Centre for Australia-India Relations, the project has involved extensive collaboration between experts from India and Australia to better understand and restore the collection.

For QAGOMA, which has so far focused mostly on contemporary Indian art, it is a step into an entirely new terrain. “You really don’t see Ravi Varma’s work in Australia, except perhaps rarely in a museum,” says Tarun Nagesh, curatorial manager of Asian and Pacific art at QAGOMA. “We wanted to share the story of this unique artist with non-Indian viewers here. Like Katsushika Hokusai, who had an incredible mainstream impact out side of his home country Japan, Ravi Varma’s story, too, deserves to be known all over the world.” Interestingly, the collection will be shown alongside contemporary art from Asia, including paintings by Indian artist Jangarh Singh Shyam, to showcase the diverse origins of religious iconography in different cultures. “The aim is to see how these artists craft their stories and mythologies,” says Nagesh, “and how their art becomes an expression of everyday faith.”

THE PRINCELY PAINTER

Over the last two decades, the commercial success of Indian art on the global stage has been dominated by the modernists. Members of the so-called Progressive Artists’ Group. M.F. Husain, V.S. Gaitonde, S.Z. Raza, F.N. Souza, Tyeb Mehta and their peers have fetched astronomical prices in auctions. Contemporary Indian art has become increasingly visible and influential. Yet, none of the Old Masters or their younger luminaries have had such an outsized impact on Indian public life as Ravi Varma.

How many Indian artists enjoy the “honour” of seeing their art turn into pop cultural nuggets like Ravi Varma’s paintings have? Or, for that matter, have the subjects of their art refashioned into an eclectic range of merchandise—cushion covers, coasters, mugs, and so on? (Journalist Akshaya Mukul, author of Gita Press and the Making of Hindu India, tells me that a member of his wife’s family even had a deck of cards printed by Raja Ravi Varma’s printing press with his signature iconography.)

So, what explains the artist’s enduring appeal outside of the closed portals of academic interest or commercial enterprises like galleries and auctions? It’s tempting to read the story of Ravi Varma’s ascent as a parable for what it means to be modern and Indian. His life and career are a bundle of contradictions. A conservative, upper-caste man, with close links to the royal family of Travancore, he took up a profession that was considered beneath his station during his time. He then learned to paint by observing Dutch painter Thomas Jensen at work. Out of this very rudimentary “training”, he forged his own style—a unique blend of Western and Eastern practices.

Most outrageously of all, he didn’t want to cater to the wealthy alone but aspired for the kind of fame that brings what we now call “virality”. So, he opened a printing press to disseminate his work as cheap and cheerful prints. “Contemporary artists from the Bengal School (originating in the early 20th cen tury) believed that art had to be rarefied, it couldn’t belong to every home,” says Shivaswamy, who is writing a six-volume study of Ravi Varma, of which three are out. “But Ravi Varma held a radically different point of view. He wanted to democratise his art so that it could belong to anyone.”

Ravi Varma was the first painter to provide a unique visual template to millions of deity-worshipping Indians. As his chromolithograph prints became popular, they were plagiarised or reproduced in leading journals and magazines of the 20th century, especially after his death in 1906. In an interview with the digital art journal Abir Pothi in 2023, Mukul explained, “The technology of chromolithography helped… (the) publications of Gita Press to bring gods to our homes. In that sense, we don’t know how Ram looks, do we? We only know it through the drawings of Gita Press.”

ART AS POLITICS

Seen through the lens of our time, Ravi Varma’s art might seem to pander to the ascendant notion of reimagining the nation as a Hindu rashtra. He did heavily rely on Hindu myths, legends and epics for his subjects. Most of his main characters are fair-skinned women, affirming their upper-caste status. They also appear docile and exude a “coy eroticism,” as Mukul puts it. But there is more to his art than meets the eye. “Ravi Varma’s art was always a political project,” says Deepanjana Pal, the author of The Painter: A Life of Ravi Varma. “He picked a medium—oil painting—that was technically barred to Indians.”

Art writer Geeta Kapur also describes Ravi Varma’s flouting of tradition as “the struggle of a prodigy to steal the fire for his own people” in her critically acclaimed study, When Was Modernism. Unsurprisingly, this narrative of an Indian artist’s rebellion against foreign exclusivity over a format (oil painting) was co-opted by leaders of the nationalist movement like Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Kakasahib Khadilkar. As visual historian Christopher Pinney explains in Photos of Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India, such appropriation of Ravi Varma’s art was a low-hanging fruit. Even progressive thinkers like Ramananda Chatterjee considered Ravi Varma “as a protagonist in the task of nation building,” Kapur adds. The nationalist agenda, as the project of political modernity has repeatedly shown, can never remain untainted by supremacist impulses.

“Ideologically the classical past is set against the medieval, regarded as having been corrupted by a medley of foreign influences…,” as Kapur explains. “Not only Islamic but curiously also Buddhist culture… is largely excluded when a civilisational memory of India is sought to be awakened. By deduction the touchstone for the nineteenth-century Indian renaissance is clearly Hindu civilisation.”

The long arm of this problem of appropriation continues to hold contemporary India in its thrall. If Ravi Varma’s art has entered the visual lexicon of militant Hinduism, it’s beyond anyone’s control. “Every culture starts as a cult, controlled by a few people,” as Shivaswamy puts it. “Once it enters the collective, it doesn’t belong to anyone.” Or, rather, it belongs to everyone— from the god-fearing ordinary Indian who says a silent prayer when faced with a deity on a calendar to the gleeful meme maker on the internet, who wants to take the micky out of Ravi Varma’s “emasculated women”, who are “infantilised and objectified, reduced them to their tender est and softest versions,” as Pal says. Much as the artist might have hated the ‘meme-fication’ of his art, he would have loved the attention. “He would have certainly enjoyed the millions of likes on Instagram,” adds Pal. “He would have valued the virality and the public access to his art.”