The Labour government responded in two ways. One was work to replace the Resource Management Act. The coalition built on Labour’s work to produce its proposed replacement.

The other was the creation of the Infrastructure Commission. It may yet prove Labour’s most durable legacy. Its establishment was quietly bipartisan — and it remains so today.

Last year the commission released its first draft National Infrastructure Plan. Its most important recommendation is also its least glamorous: maintain what we already own and make better use of it.

New Zealand has leaky hospitals, failing pipes and deteriorating schools because assets are neglected once the ribbon-cutting is over. Every homeowner knows that if gutters are not cleaned, the eventual repair bill can be enormous. So too for central and local government.

The commission estimates that around 60% of infrastructure investment needs to go to maintaining and renewing existing assets.

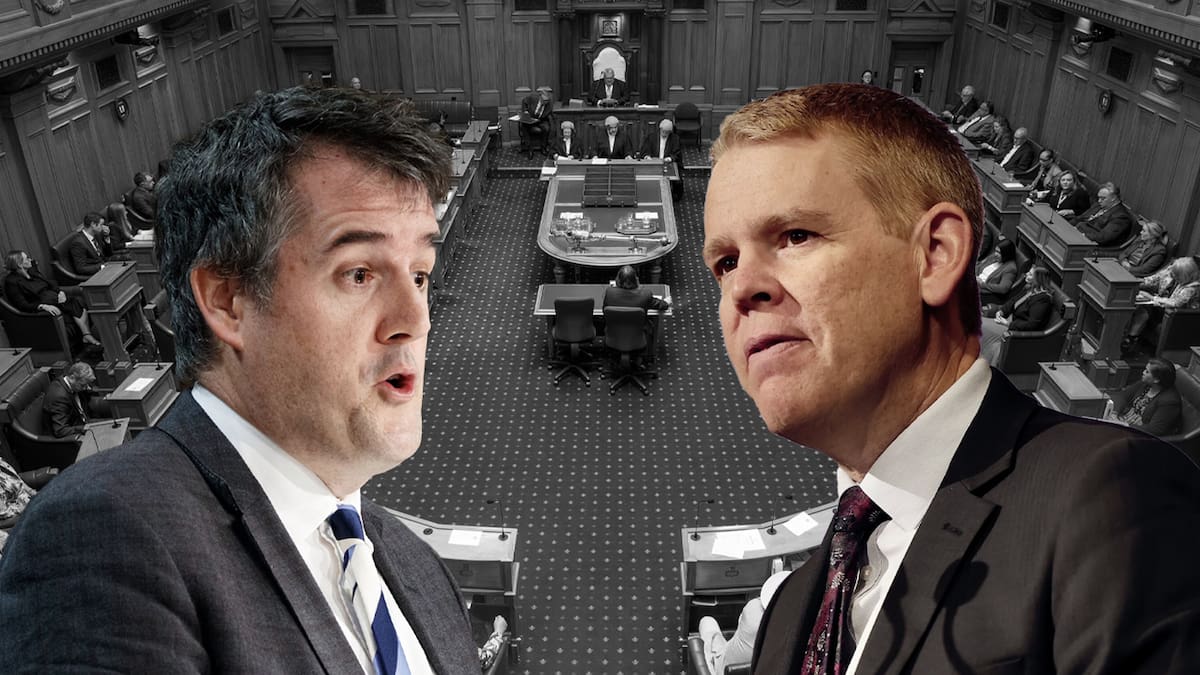

Infrastructure Minister Chris Bishop has adopted this emphasis on maintenance and launched an all-of-government programme to address long-standing shortcomings.

While Labour has not endorsed this shift, it has not criticised it.

The commission’s draft plan proposes that roads, water, electricity and telecommunications should largely be user-pays, while social infrastructure — schools, hospitals and courthouses — should be funded by taxpayers.

The biggest funding gap is roads. Before more fuel-efficient vehicles, roads were almost entirely user-pays. Fuel taxes are now declining. As a driver of a hybrid vehicle, I pay only a fraction of the fuel tax I paid a decade ago.

The Government has announced it will move to a fairer user-pays model. While seeking details, the Opposition leader has acknowledged that the move is inevitable.

The legislation enabling congestion charging was supported by all parties.

This is promising. But no government has been elected pledging to be a better steward. Many politicians have been elected promising new infrastructure.

The commission recommends that all new projects pass three tests: alignment with national priorities, value for money — meaning benefits exceed costs over the life of the asset — and realistic deliverability.

Again, while Labour has not endorsed this approach, it has not rejected it.

That may be because “national priorities” can mean almost anything: net-zero emissions, regional development or more liveable cities.

The emerging consensus may exist because the commission’s plan is not really a plan but a strategic approach. That makes agreement easier, but also avoids choosing between competing priorities.

I am sceptical about how helpful the commission’s tests will be in practice. A Green minister may prioritise zero emissions: a New Zealand First minister regional development. Ensuring benefits just outweigh costs stops white elephants but permits low-value projects.

Cabinet rules require regulations to be justified by cost–benefit analysis, so why are costly infrastructure projects not held to the same standard?

Cost-benefit analysis cannot capture every social value because it depends on how benefits are priced. When I was Minister of Transport, the National Roads Board’s cost-benefit analysis did not value safety highly enough to justify motorway safety barriers.

Horrified by head-on motorway crashes from cars crossing into oncoming traffic, when I became Minister of Works, we mandated safety barriers. But we retained cost-benefit analysis to decide which new roads to build. It is not a perfect test, but better than any other.

A national framework that does not use cost-benefit analysis to rank projects leaves infrastructure decisions to politics, not value.

Frameworks do not make decisions, ministers do. Too often projects – light rail schemes or harbour bridge cycleways – are announced before there is even a business case.

Here is a better test: use the National Infrastructure Framework to assess the 140 planned projects costing more than $100 million each, then rank them by value using cost–benefit analysis.

If the parties commit to maintaining what we have, to users funding networks, applying the commission’s tests to new projects and rank projects by cost/benefit, New Zealand will have taken a decisive step forward.

But if parties promise infrastructure that meets no test, the emerging consensus will prove an illusion — and the country will go on wasting billions.

Stay ahead with the latest market moves, corporate updates, and economic insights by subscribing to our Business newsletter – your essential weekly round-up of all the business news you need.