Opinion: In 2024, my family and I lived through the civil unrest crisis in New Caledonia. As New Zealand’s Consul-General to the French Pacific, I helped coordinate the safe return of Kiwi tourists, including through seven evacuation flights out of Nouméa.

As a parent, living through the riots was a frightening and demanding experience for my two young children, and scary for my husband, stuck back in Auckland watching it all on the news.

Yet it was also an enormous privilege to support so many New Zealanders in need. I still remember the sense of relief as we watched the first flight depart with our most vulnerable Kiwis, quickly followed by the realisation of how many more still needed help.

Working with our small team, colleagues in Wellington, the French Government and the New Zealand Defence Force, we achieved what at times felt like a herculean task.

Ultimately under the leadership of the Prime Minister, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Minister of Defence, we brought more than 360 New Zealanders and other nationals to safety — a defining moment in my career and one that taught me a great deal about crisis management.

When my posting finished and we returned to New Zealand, it felt like time for a change.

The opportunity came up to be executive director of the International Business Forum. This meant stepping into the shoes of the inimitable Stephen Jacobi and there have been many jokes about footwear (Stephen’s shoes are bigger but I can go further in a pair of heels).

In the new role I hoped to use my foreign policy experience to help businesses interpret and respond to international events, in a world of increasingly turbulent geopolitics.

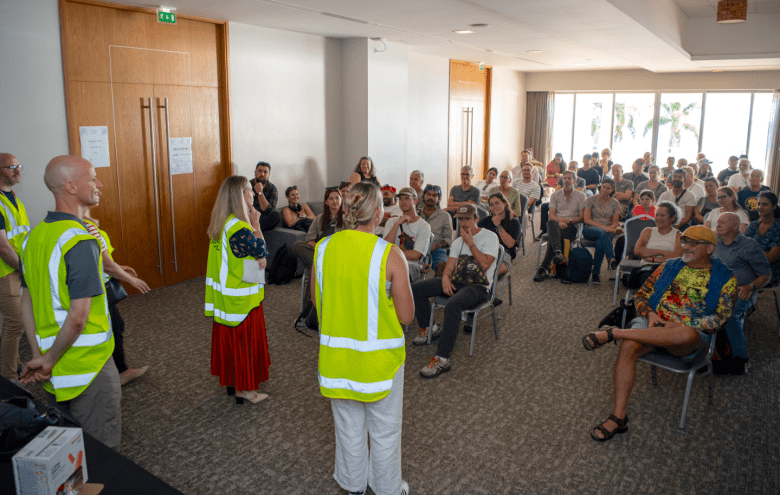

As Consul-General to New Caledonia, Felicity Roxburgh briefs New Zealanders being evacuated from Nouméa in 2024. Photo: NZDF

As Consul-General to New Caledonia, Felicity Roxburgh briefs New Zealanders being evacuated from Nouméa in 2024. Photo: NZDF

Start your day informed. Make room for newsroom’s top stories. Direct to your inbox daily.

It turned out that having a bit of crisis management experience was pretty useful too.

When the US announced a 15 percent so-called “reciprocal” tariff on NZ’s goods, the media interest was intense, and the International Business Forum played a key role as media commentator. This was very much out of the comfort zone of a former official!

Early morning radio interviews had to be conducted from inside my car, parked in the driveway, hiding from those same small people who had lived through the unrest. Crisis communication again was key. New Zealanders wanted to understand what was unfolding and what it meant for us as a small, remote nation dependent on exports.

Never has the modern global trading system been more in crisis mode than in 2025. In real time we are watching the system we have relied upon since the Second World War come under serious pressure.

Great power competition has meant countries are thinking more about ensuring their security than openly trading with each other. Supply chain management has become more about ensuring control over critical elements, than integrating more closely with key economic partners.

Others are turning to protectionism to shield key industries from market-forces, and some of the rules of the World Trade Organization are seemingly thrown by the wayside.

None of this is good news for New Zealand.

Those of us immersed in trade and foreign policy often talk about the international rules-based order. I was surprised when one radio presenter put to me that New Zealand should “just get over it”, and that the rules were dead.

While the international rules-based order doesn’t exactly make for light and tasty summer beach reading, it matters deeply for a country like New Zealand.

With little hard power, we depend on the rules of the game being fair. Our businesses need certainty and a level playing field to sell their goods and compete abroad. We need stability so that our companies can invest, hire workers, grow the economy.

And fairness is a core New Zealand value – having a “fair go” sits at the heart of the multilateral system.

In the NZ Herald Mood of the Boardroom survey this year, business leaders ranked geopolitics as their top international concern.

A further 78 percent of chief executives said their boardrooms now regularly assess geopolitical vulnerabilities as part of their governance practices. This is more than good business sense, but key to successfully navigating the period ahead.

Since starting in the role, I’ve also learned more about how our savvy exporters manage all sorts of risk – currency fluctuations, logistics disruptions, legal and financial risk, customs delays and commodity price volatility – to name a few.

We can cope with geopolitical risk too.

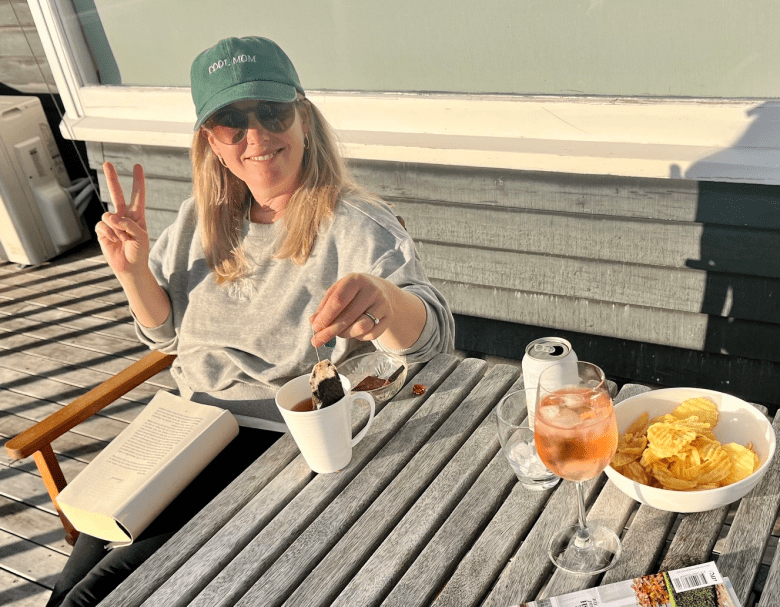

Falling back on protectionism is a bit like all agreeing to do ‘dry July’ and then someone has a glass of champagne on their birthday, says Felicity Roxburgh. Next thing we’re all back to the G&Ts and no one can remember why we believed in the system to begin with. Photo: Supplied

Falling back on protectionism is a bit like all agreeing to do ‘dry July’ and then someone has a glass of champagne on their birthday, says Felicity Roxburgh. Next thing we’re all back to the G&Ts and no one can remember why we believed in the system to begin with. Photo: Supplied

So, what to hope for in the world of international trade in the new year?

Hope is the key word here. I hope we will see more stability in our international environment or at least fewer crazy random surprises.

We need more certainty about the future to boost our confidence at home and to succeed abroad.

I hope we will see fewer countries fall back on protectionism, despite fears over economic vulnerabilities. For the rules of the game to work, all countries big and small need to continue to buy into the pact. Falling back on protectionism is a bit like all agreeing to do ‘Dry July’ and then someone has a glass of champagne on their birthday. Next thing we’re all back to the G&Ts and no one can remember why we believed in the system to begin with.

I hope we will see stronger coalitions emerge of those countries that still believe in the power of free and open trade to lift all our fortunes. And as we ring in 2026, the freshly minted New Zealand-India FTA is a heartening example of big and small countries doing exactly that.

While we can hope for the best, we must also plan for the worst. Businesses need to undertake careful scenario planning, cut through the noise to identify credible, actionable information, and actively assess their market optionality – the ability to spread risk across markets as conditions change.

Doing so will require the same grit, determination, and commercial nous that have long defined New Zealand’s impressive exporting community.

To respond to events in New Caledonia we had to develop plans quickly, test them, and sometimes abandon them completely as conditions shifted hour by hour. New Zealand is known for this kind of clever, flexible problem-solving, and I have seen our exporters apply the same mindset in confronting global uncertainty.

That same resilience will serve us well in 2026: staying alert, adapting early, and shaping our own path. I know New Zealand can meet even the most unpredictable global challenges.