Neptoon Records owner Rob Frith, shown at his Vancouver shop on April 4, 2025, holds a reel-to-reel tape that contains a master-generation recording of the Beatles’ failed Decca Records audition in 1962.Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail

Rob Frith has owned Neptoon Records, a shop in Vancouver, since 1981. Over the decades, records and tapes have come into the store through informal channels: estate sales, retired sound engineers, collections that no longer have a home. Some sell quickly. Others sit behind the counter for years.

Frith doesn’t rush these things. He has learned that value does not always announce itself immediately.

Last year, one of those objects – a reel-to-reel tape Frith had long assumed was a degraded copy – turned out to be something far more meaningful. It was a remarkably clean master-generation recording of the Beatles’ failed Decca Records audition, long believed to be lost.

Recorded on Jan. 1, 1962, the session captured the band before they were signed, before Ringo Starr joined and before history closed around them. The Beatles recorded 15 songs that day – a mix of covers and a few early originals – only to be turned away by Decca executives, who reportedly told them that “guitar groups are on the way out.”

Frith never considered selling the tape.Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail

Last March, Frith gave me a private listening session. Although fragments of the audition have circulated for decades in bootleg form, the tape he discovered plays with a clarity that suggests it is closer to the source than any version previously available. It documents a band that sounds capable but not yet assured, ambitious but still exposed. I called it a revolution.

When the tape became public, the reaction was immediate. People asked Frith what he intended to do with it. Would he sell it? Did he understand how much it might be worth?

Since I first spoke with Frith, his answer never changed. He did not want to sell it. However, if Paul McCartney wanted it, he would give it back.

“I just thought maybe it was a nice thing to do,” he told me recently from his home in British Columbia. “They’re the guys that recorded it.”

That response puzzled some people and angered others. Online commenters called him foolish. Frith said he did not view ownership the way they did. The tape had come to him by accident. He had not made it. He had not lost it. It had passed briefly through his possession, and that, he said, shaped what he felt entitled to do with it.

We tend to treat possession as proof of entitlement. In that framework, the question is not “what is this” but “what can this be turned into.” Frith treated the tape less like an asset than something he was responsible for.

Paul McCartney gestures to the crowd during his Got Back North American tour at TD Coliseum in Hamilton, Ont., on Nov. 21, 2025.Nick Iwanyshyn/The Canadian Press

Shortly after our listening session, a call from Paul McCartney’s representatives put that approach to the test. They had read about the tape in The New York Times and, Frith told me, appreciated that he was not trying to monetize it.

Frith doesn’t like travelling by plane, but after months of back and forth, he was convinced to fly to California last September with his wife and two sons to return the tape to McCartney in person.

They met at a non-descript warehouse in Los Angeles where McCartney was rehearsing for his upcoming tour. The space was expansive, closer to an industrial sound stage than a concert venue. In the middle of the room sat a single couch, the only piece of furniture.

Frith thought the meeting would be brief. He handed over the tape, and more or less expected that exchange to mark the end of it. Instead, McCartney walked over and greeted him by name.

“He gives me this big hug and says, ‘Nobody does what you’re doing anymore,’” Frith told me. “He was very emotional.”

They ended up speaking for nearly two hours. At some point, Frith asked about the demo recording, and McCartney recalled being deeply hungover (it was New Year’s, after all). Eventually, McCartney invited Frith and his family back the following day.

When they returned, the Friths were once again sat on the same couch, the only audience to McCartney and his band rehearsing for a full arena show. “We’re sitting there watching an hour-and-a-half of a Paul McCartney show,” Frith said. “And every once in a while, he’d wave to us from the stage.”

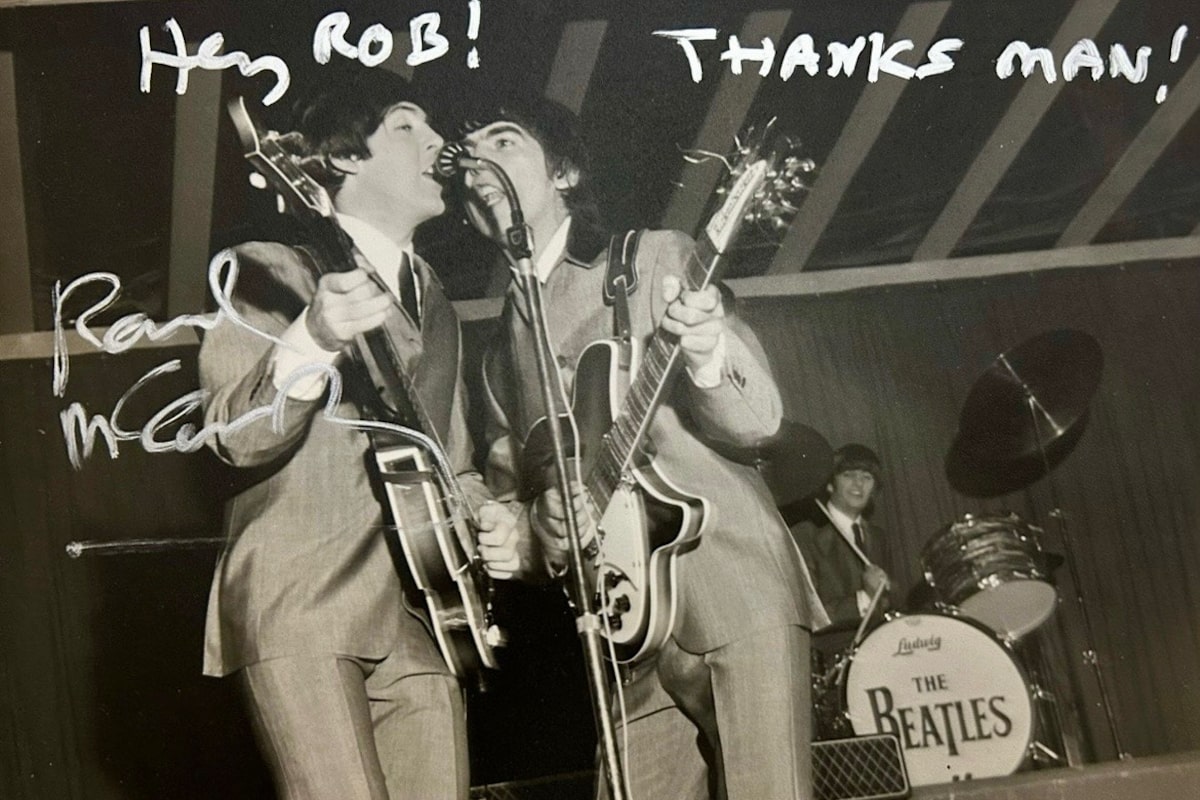

Frith didn’t leave the meeting empty-handed.Supplied

Since returning to Vancouver, Frith has been asked repeatedly whether he regrets not selling the tape. He told me he does not. “I would never change it,” he said. “We got more than money. To meet your favourite artist and discover that he’s a very nice person, better than you thought he was going to be – that was everything.”

Frith isn’t sure what McCartney plans to do with the tape. He thinks it might make a good Record Store Day release. For those who have heard it, and those who may one day, the tape represents something increasingly rare: a moment before history, before certainty, before myth, which hardens effort into inevitability. That is what makes it intimate.

In 2026, intimacy of that kind feels harder to come by. We live amid perfect reproductions, algorithmic nostalgia and objects designed to circulate endlessly without ever being touched. Ownership has thinned into access rights, subscriptions, digital proofs. Even memory now arrives preprocessed, optimized for sharing rather than keeping.

In that context, the idea that something could be held briefly, cared for and then returned, without being monetized, leveraged or turned into narrative capital, feels almost oppositional. Frith’s decision refused the logic of optimization.

What lingers is a softer question: What does it mean to care for something you were never meant to own? And what obligations come with possession that is temporary, accidental or ethically thin?

These days, Frith is back at Neptoon Records, preparing for its upcoming 45th anniversary. Objects continue to arrive, others leave. Some remain on shelves, waiting.

“There’s always something,” he told me when I visited the store last March. “You just have to know where to look.” And sometimes, what not to keep.