Trypanosoma brucei contains two related aquaglyceroporins, TbAQP2 and TbAQP3, with only TbAQP2 being able to transport pentamidine and melarsoprol into the trypanosome (Baker et al., 2012; Munday et al., 2014). Drug resistance has arisen through recombination between the two genes and the expression of TbAQP2–AQP3 chimeras (Graf et al., 2015; Graf et al., 2013; Pyana Pati et al., 2014). There are 68 amino acid residues that differ between TbAQP2 and TbAQP3, and the drug-resistant chimeras can contain 20–43 differences to TbAQP2 (Figure 1). A number of these residues have been mutated individually in attempts to identify key residues involved in drug translocation and thus potentially resistance. At the intramembrane ends of the two transmembrane half-helices H3 and H7 are the aforementioned NSA/NPS motifs, Asn130–Ser131–Ala132 and Asn261–Pro262–Ser263, respectively (Figure 4a). In aquaporins such as TbAQP3, these conserved residues are the canonical NPA/NPA motifs, and mutations were made (S131P + S263A) to convert the NSA/NPS motif in TbAQP2 to NPA/NPA. This resulted in a 95% reduction in pentamidine transport by the mutant, although this was still measurably higher than that observed in a TbAQP2 knockout cell line (Alghamdi et al., 2020) and a similar reduction in the transport of the melarsoprol analogue cymelarsan (Figure 6). The cryo-EM structures show that both Ser131 and Ser263 are critical in stabilising this region of the transporter through specific hydrogen bonds with Gln155 and the backbone amine group of Ala132 (Figure 4a) and do not make any direct interactions either to the drugs or the glycerol molecules. Thus, the decrease in pentamidine uptake observed in the S131P + S263A TbAQP2 mutant is probably more complex than previously thought, as it seems unlikely to have arisen through simple changes in transporter–drug interactions or a narrowing of the channel.

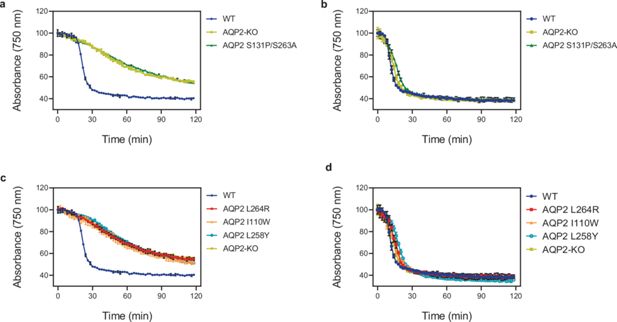

Lysis assay of T. brucei cells.

Lysis assay with T. b. brucei wild-type and various AQP2 mutant cell lines treated with arsenical compounds: (a, c) cymelarsan; (b, d) phenylarsine oxide, a different arsenic-containing trypanocide that enters the parasite independently of TbAQP2 (Munday et al., 2015b; De Koning, 2001; Munday et al., 2014) and is thus used as a control for transporter-related arsenic resistance versus resistance to arsenic per se. The cells were placed in a cuvette and treated with either compound at t = 10 min. All points shown are the average of triplicate determinations and SD. When error bars are not visible, they fall within the symbol. The slow decline with cymelarsan over time in AQP2-KO and the mutant cell lines is attributable to residual uptake of the compound through the TbAT1/P2 transporter (Carter and Fairlamb, 1993; de Koning et al., 2000).

Based on a previous modelling study, several other mutations were predicted to potentially affect drug uptake in the TbAQP2–TbAQP3 chimeras (Alghamdi et al., 2020). Based on the cryo-EM structures, the mutated residues fall into three distinct groups: those not in the channel (I190T and W192G), those lining the channel and within van der Waals distance of pentamidine (I110W, L258Y, and L264R) and those lining the channel, >3.9 Å from pentamidine and observed to make contacts to pentamidine during MD simulations (L84W/M, L118W/M, and L218W/M). In all instances, there was a >90% decrease in pentamidine uptake and in many cases no residual pentamidine transport was detected (e.g. I110W, L264R, and L84W) (Alghamdi et al., 2020). To understand the molecular basis for the dramatic decreases observed in pentamidine transport, we performed MD simulations on a subset of the mutants.

Three mutations were chosen for MD simulations (I110W, L258Y, and L264R), all of which were defective in uptake of cymelarsan (Figure 6) as well as pentamidine (Alghamdi et al., 2020). These three residues all make high occupancy contacts to pentamidine in the MD simulations (Figure 5—figure supplement 1b) and residues Ile110 and Leu264 make van der Waals contacts with pentamidine in the cryo-EM structure (Leu258 is 5.5 Å away from pentamidine). The double mutant L258Y + L264R was used in the MD simulations as this is found in a number of drug-resistant T. brucei strains such as P1000 and Lister 427MR (Munday et al., 2014). The mutant I110W is found in the T. brucei drug-resistant strain R25 (Unciti-Broceta et al., 2015), but in the absence of the L258Y + L264R double mutation (Figure 1). Therefore, we performed atomistic MD simulations of monomeric TbAQP2 with either the I110W (hereafter IW) or L258Y + L264R (hereafter LY/LR) mutations present, as well as with wild-type monomeric TbAQP2. Each protein was simulated both with pentamidine bound and removed (apo). The mutations do not affect TbAQP2 stability (Figure 2—figure supplement 6e), but do destabilise pentamidine binding, causing it to shift away from the initial binding pose along the z-axis (Figure 5—figure supplement 1c), suggesting a lowered affinity for the structural pose. The pore radii are unchanged by the mutations (Figure 5—figure supplement 1d), meaning that this effect is likely to be a loss of specific interactions rather than a more general effect on protein structure.

We next computed energy landscapes for pentamidine moving along the z-axis through the channel using potential of mean force (PMF) calculations with umbrella sampling. The data for WT TbAQP2 reveals a clear energy well for the structurally resolved pentamidine at –0.2 nm (Figure 5d, Figure 5—figure supplement 3b). The depth of this well (–40 kJ/mol) suggests a very high-affinity binding site, consistent with previous kinetic analyses (Bridges et al., 2007; De Koning, 2001; Teka et al., 2011), and is much higher than previously investigated docked poses (Alghamdi et al., 2020) of pentamidine in models of TbAQP2. Notably, this energy well is much shallower for both the IW (–20 kJ/mol) and LY/LR mutants (–25 kJ/mol), representing a relative reduction in binding likelihood of about 2800- and 400-fold, respectively. In biochemical terms, these changes would result in a Km shift from ~50 nM to 50 or 300 µM, respectively, all but abolishing uptake at pharmacologically relevant concentrations; the experimental Km for pentamidine on wild type TbAQP2 is 36 nM (De Koning, 2001). The reduction in pentamidine binding likelihood is consistent with the increased z-axis dynamics seen in Figure 5—figure supplement 1c. Flanking the central energy well are large energy barriers at about –0.7 and 1 nm (Figure 5d), similar to those seen for urea translocation in HsAQP1 (Hub and Groot, 2008). These would presumably slow pentamidine entry into and through the channel, and previous studies did reveal a slow transport rate for pentamidine (De Koning, 2001; Teka et al., 2011). We note that previous studies using these approaches saw energy barriers of a similar size, and that these are reduced in the presence of a membrane voltage (Alghamdi et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2024). The energy barriers are highest in the IW mutant, and interestingly, the inner (–0.7 nm) barrier is lower in the LY/LR mutant (Figure 5—figure supplement 3e). In all cases, especially WT, small energy minima are observed at about –1.35 and +2.7 nm; these represent the drug binding at the entrance and exit of the channel (Figure 5—figure supplement 3d). The differences in landscape between the WT and mutants help explain how these mutations confer a resistance to pentamidine, mostly through reduced binding affinity.