This ancient, leg-bearing snake is rewriting the story of how serpents slithered, and sometimes walked, their way through evolutionary history.

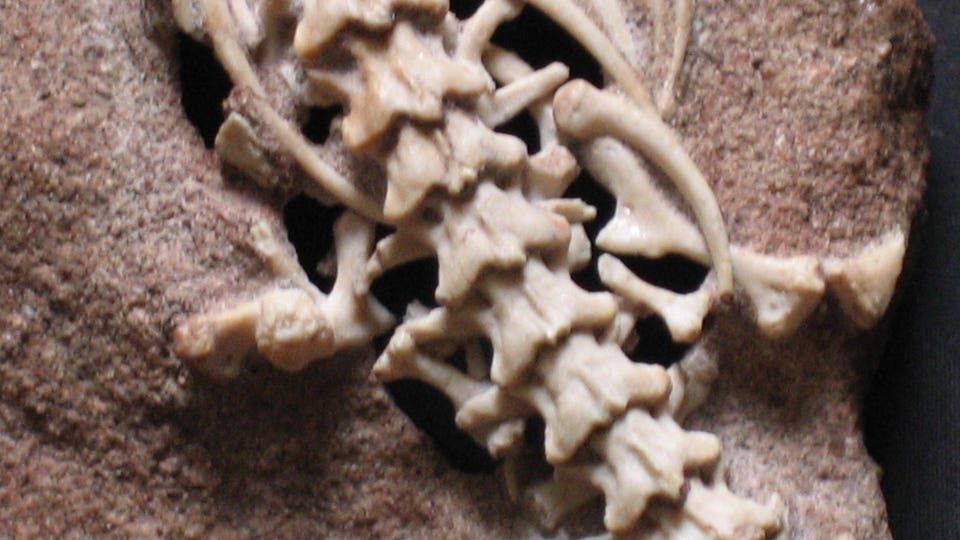

Paleoninja, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

If you thought that snakes were always slithering, limbless creatures, then you’d be mistaken; hundreds of millions of years ago, snakes crawled before they slithered. However, deep in the Patagonia badlands of Argentina, one fossil has been undoing decades of assumptions about this part of snake evolution.

Najash rionegrina was a Cretaceous basal snake that moved around with hips and hindlimbs — at the same time that limblessness was actively becoming the norm. Here’s how Najash taught herpetologists that serpentine body plans didn’t evolve in a straight line, from lizard to legless.

A Snake With Legs

In a 2006 study published in Nature, paleontologists Sebastián Apesteguía and Hussam Zaher described a never-before-seen fossil: a 90-million-year-old basal snake with a pelvis and well-developed hindlimbs. Importantly, these weren’t vestigial spurs — the claw-like remnants of hind legs that we see on some modern boas and pythons. These were real legs that were clearly connected to a bony sacrum.

At the time, the majority of fossilized snakes that had leg remnants (like Pachyrhachis, Haasiophis or Eupodophis) were found in marine rocks. On top of this, most of them also lacked a true sacrum. This made Najash radically different for three primary reasons:

It came from terrestrial sediments in the Candeleros Formation of Patagonia, not marine rocksIts hindlimbs extended outside the ribcageIts pelvis was firmly attached to the backbone, which suggests that it had a genuinely functional role, and that it wasn’t just an evolutionary leftover.

For herpetologists, these three discrepancies alone instantly made Najash one of the most crucial specimens for understanding snake origins and limb loss.

However, a stunning revelation from a 2019 study published in Science Advances is that Najash didn’t just briefly have legs as a transitional phase between lizardness and leglessness. In reality, the fossil record suggests that they kept them for tens of millions of years. The study used high-resolution CT scans of eight novel Najash skulls to map out early snake anatomy. These scans revealed a mix of features paleobiologists had never seen before:

Lizard-like characteristics. These included cheekbones (jugal bone) that aren’t seen in modern snakes.Snake-like innovations. Specifically, skull mobility, which we see in present-day serpents.

These modern findings further reinforce the fact that Najash and its kin weren’t evolutionary “mistakes” on the road to leglessness. They were successful animals with limbs that stuck around longer than many scientists expected — roughly 70 million years of hindlimb-bearing snake diversity.

Why This Snake Kept Its Legs

Leg loss in snakes was neither a fast nor a uniform process. Instead, genetic and fossil evidence suggest that limb reduction most likely happened in gradual phases. Specifically, forelimbs were lost early, while hindlimbs lingered for a long time in some ancient lineages. Some modern boas and pythons still have tiny residual pelvic “spurs” on their sides from this era.

Fossils of Najash and its fellow leg-bearing counterparts all come from a time when snakes still had varying degrees of limbs and skeletons; it was almost as though there were separate evolutionary experiments running simultaneously.

This begs the question: Why didn’t species like Najash lose their legs immediately like other snakes? Paleontologists think this is likely because Najash’s legs offered functional advantages early on, perhaps for anchoring during burrowing or grasping prey. These would have been useful traits in a world full of small mammals, lizards and dinosaurs.

This is also what makes Najash stand out from other legged snakes from the time — that is, that its hind legs were anatomically connected to a pelvis and vertebrae in a way that suggests it actually used them daily. Pachyrhachis or Eupodophis’ anatomy suggests that their legs likely weren’t functional.

Najash’s is also an outlier because its skull is a mosaic of both lizard-like and snake-like features. The Science Advances researchers revealed that its cheekbone, which was once thought to be altogether absent in all snakes, was actually present in this ancient genus. This further undermined herpetologists’ ideas regarding snakes’ evolutionary timeline; some “classic” snake traits clearly evolved gradually, and in a surprising order, too.

At the same time, the earliest snakes appear to have had partial skull flexibility, somewhere between rigid lizards and modern snakes. This also hints at incremental adaptations for predation and feeding. Najash’s remains offer us a glimpse into how complex features like flexible jaws arose over millions of years, rather than all at once.

Why This Snake Matters

Uncovering Najash’s place in the snake family tree has been eye-opening. Studies that map evolutionary relationships consistently place Najash outside the crown group of modern snakes. This makes it one of the most basal, or primitive, branches of Serpentes.

That classification means Najash isn’t just a weird side-branch of the snake family tree. In fact, it makes Najash crucial for understanding early snake evolution, right at the point where classic lizard traits gave way to snake features.

Some researchers believe that snakes used to occupy a much wider variety of ecological niches (burrowing, terrestrial, aquatic) before the increasingly limbless condition became the dominant form we know today. Najash, along with other snakes with hindlimbs, supports this idea of a “bushy” evolutionary landscape, where different snake lineages experimented with body plans in different environments.

Najash’s discovery further emphasizes the fact that the fossil record is far from complete, and what we don’t yet know may very well change everything we think we know. It also shows us that evolution is rarely ever a smooth, linear transition from primitive to “advanced.” Instead, it’s full of twists and turns, like an ancient snake that held onto its legs long after most of its cousins dropped theirs.

Do snakes fascinate you, or do they make your skin crawl? Take this science-backed test to see where your snake fear really falls: Fear of Animals Scale

Curious what your inner creature is — whether it’s a snake, wolf or something entirely unexpected? Take the Guardian Animal Test for an instant answer.