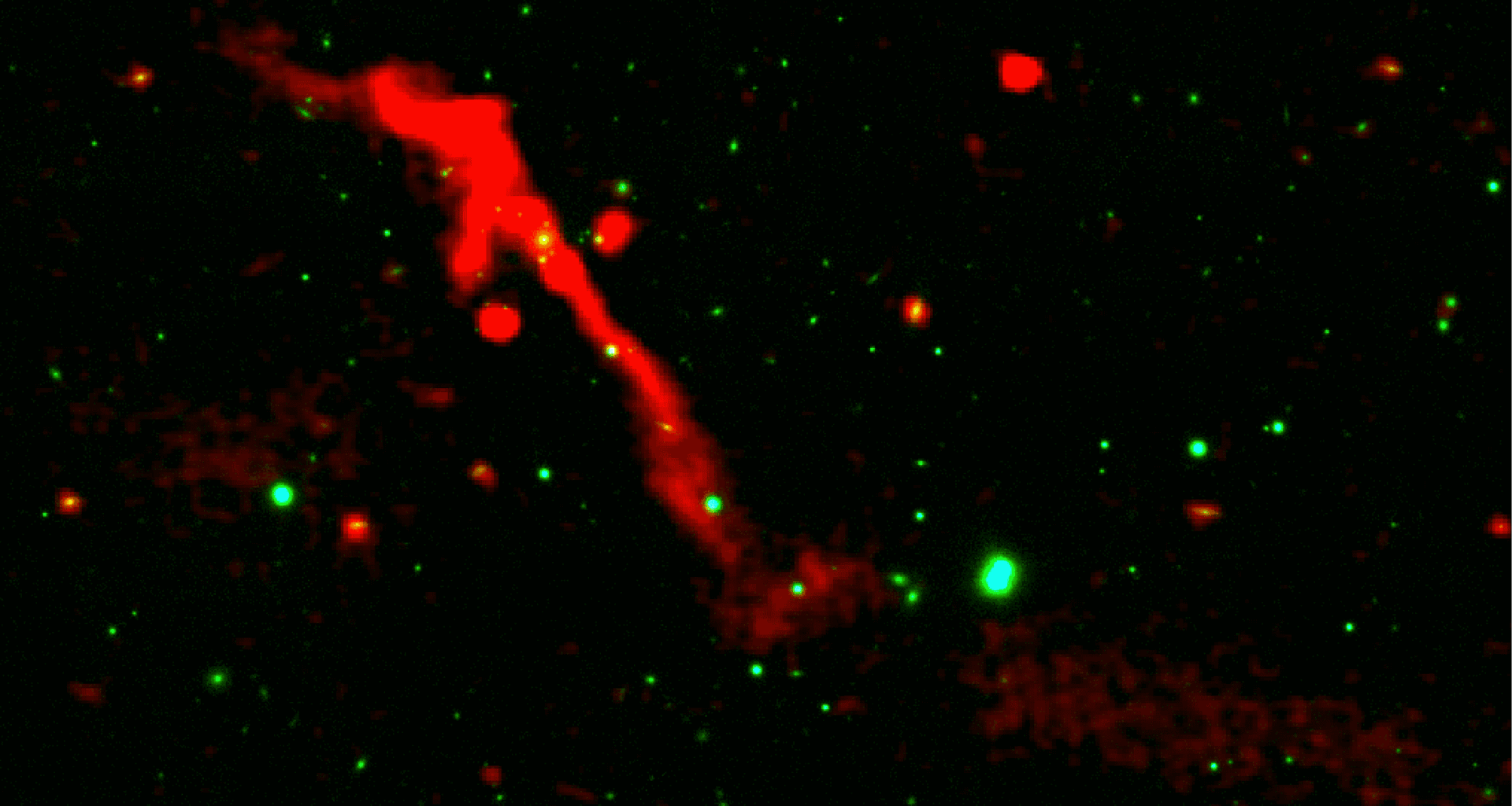

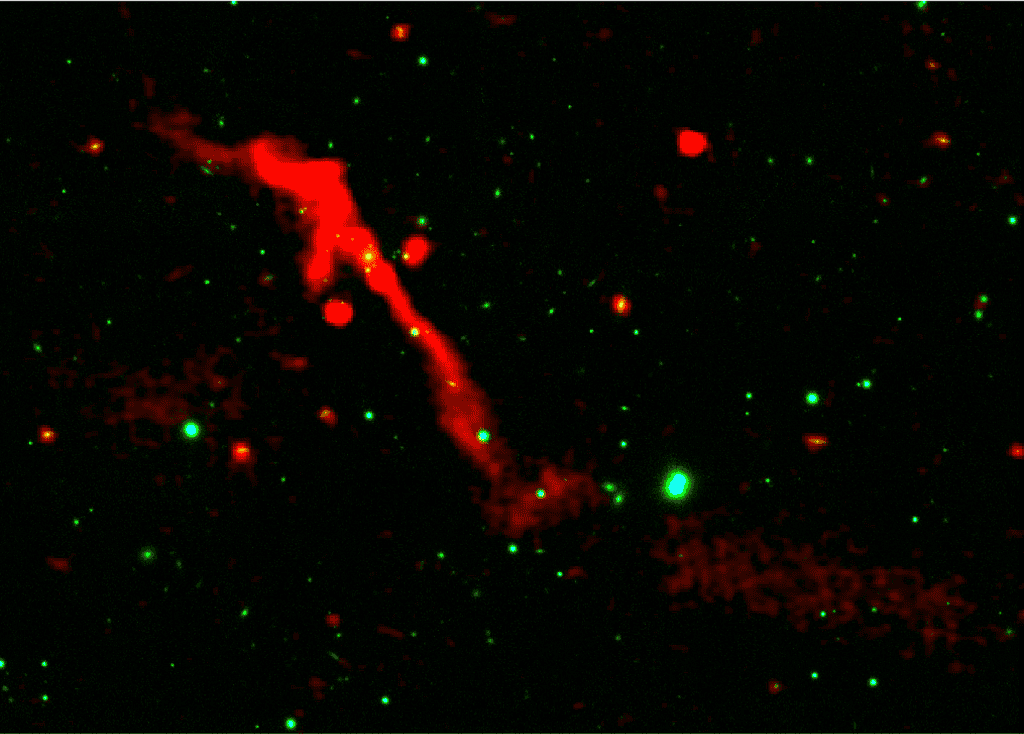

This LOFAR DR2 image of J1007+3540 superimposed over an optical image by Pan-STARRS shows a compact, bright inner jet, indicating the reawakening of what had been a ‘sleeping’ supermassive black hole at the heart of the gigantic radio galaxy. Credit: LOFAR/Pan-STARRS/S. Kumari et al.

This LOFAR DR2 image of J1007+3540 superimposed over an optical image by Pan-STARRS shows a compact, bright inner jet, indicating the reawakening of what had been a ‘sleeping’ supermassive black hole at the heart of the gigantic radio galaxy. Credit: LOFAR/Pan-STARRS/S. Kumari et al.

Deep in the cosmos, about a billion light-years away, a monster with a gargantuan appetite has woken up. For roughly 100 million years, the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy J1007+3540 was silent. It sat quietly in the dark, surrounded by the cooling remnants of its past tantrums. But recently (in cosmic terms), it turned back on.

Astronomers have captured a vivid portrait of this “reborn” activity, revealing a chaotic struggle of gas, dust, and energy that spans nearly 1.5 million light-years, in an event likened to the eruption of a “cosmic volcano.”

The radio data clearly shows a fresh, bright inner jet punching through a cocoon of older, faded plasma — debris left over from the black hole’s previous eruptions.

“It’s like watching a cosmic volcano erupt again after ages of calm — except this one is big enough to carve out structures stretching nearly a million light-years across space,” said lead researcher Shobha Kumari of Midnapore City College in India.

In a new study, the astronomers describe this system as a rare “episodic” giant radio galaxy. It offers us a front-row seat to the life cycle of the universe’s most powerful engines, showing us that sometimes galaxy growth is less like a slow evolution and more like a series of explosive, fiery breaths.

A Messy, Chaotic Struggle

Most galaxies, including our own Milky Way, harbor a supermassive black hole. But J1007+3540 is part of an elite club known as Giant Radio Galaxies (GRGs). These behemoths shoot out jets of magnetized plasma that extend far beyond the visible stars of their host galaxy, reaching sizes that dwarf entire galaxy clusters.

What makes J1007+3540 unique is that it hasn’t just erupted once. The radio images, captured using the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) and the upgraded Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (uGMRT), show distinct layers of history. There are faint, ghostly lobes of old plasma from an ancient eruption, and nestled inside them are bright, compact jets from a new outburst.

The outer, fading lobes are estimated to be around 240 million years old, while the inner, punchier jets are much younger — only about 140 million years old. This 100-million-year gap represents the black hole’s “dormancy” before the current reignition.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

“This dramatic layering of young jets inside older, exhausted lobes is the signature of an episodic AGN (active galactic nucleus) — a galaxy whose central engine keeps turning on and off over cosmic timescales,” Kumari added.

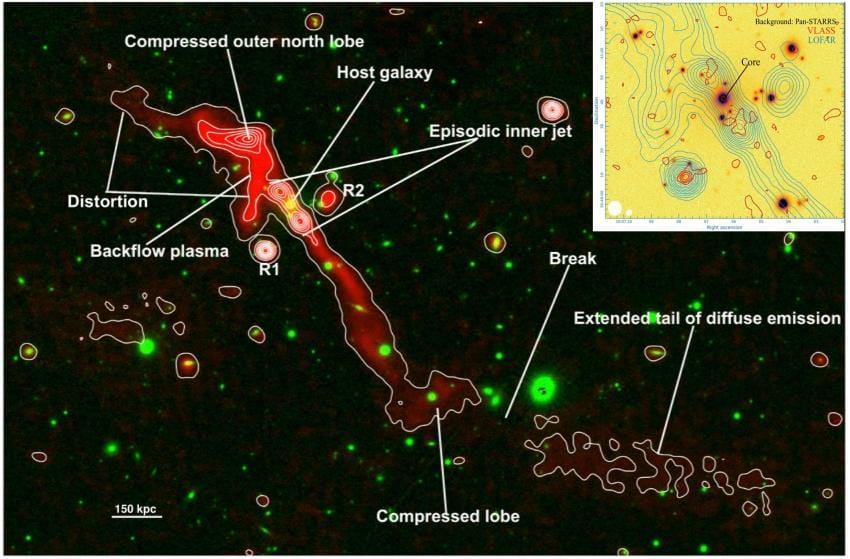

The Crushing Pressure of the Cluster

The same image as above with labels showing the compressed northern lobe, curved backflow signature of plasma and the inner jet of the black hole. Credit: LOFAR/Pan-STARRS/S. Kumari et al.

The same image as above with labels showing the compressed northern lobe, curved backflow signature of plasma and the inner jet of the black hole. Credit: LOFAR/Pan-STARRS/S. Kumari et al.

This black hole isn’t erupting in a vacuum. It lives inside a dense neighborhood called the WHL 100706.4+354041 cluster. Galaxy clusters are filled with the Intracluster Medium (ICM), which is a sort of soup of superheated gas that exerts immense pressure on everything inside it.

Usually, radio jets shoot out in straight lines. But in J1007+3540, the environment is fighting back. The pressure from the surrounding cluster gas is so intense that it is physically bending and squashing the radio jets. The northern lobe of the galaxy is “compressed and dramatically distorted,” showing a curved “backflow” where plasma is being shoved backward and sideways, unable to pierce through the dense gas easily.

“J1007+3540 is one of the clearest and most spectacular examples of episodic AGN with jet-cluster interaction, where the surrounding hot gas bends, compresses, and distorts the jets,” said co-author Dr. Sabyasachi Pal of Midnapore City College.

This resistance creates a “distorted backflow signature,” essentially a splash-back of plasma. It’s similar to what happens when a high-pressure fire hose is aimed at a brick wall; the water (or in this case, relativistic plasma) sprays back toward the source. The researchers found that this squashed northern lobe has a “steeper” radio spectrum, indicating the electrons there are very old and losing energy rapidly as they battle the cluster’s weather.

Zombie Electrons and Ghostly Tails

The southern side of the galaxy tells a different, but equally strange, story. Extending away from the core is a massive, detached tail of diffuse emission that seems to break off from the main structure.

This tail presents a mystery to the astronomers at the moment. Typically, the further plasma gets from the black hole, the older and fainter it should be. But in this detached tail, the electrons seem to be “younger” than expected, with a radiative age of only 100 million years—younger even than the inner jets.

How can the debris be younger than the eruption that created it? The authors suggest a fascinating mechanism: re-acceleration. As the tail interacts with the turbulent gas of the cluster, shocks and turbulence might be recharging the old, “fossil” electrons, giving them a burst of new energy. Essentially, the violent environment is waking up the dead plasma, making it glow brightly again like a zombie limb detached from the main body.

The Heartbeat of Galaxy Evolution

Why does this matter now? Previously, astronomers thought of galaxies as island universes that evolved in isolation. But systems like J1007+3540 show us that galaxy evolution is sometimes a contact sport. The “duty cycle” of a black hole — how often it turns on and off — regulates the growth of the galaxy itself.

When these jets erupt, they dump massive amounts of kinetic energy into the surrounding gas. This feedback can stop gas from cooling down to form new stars, effectively killing the galaxy’s future growth. Conversely, the “rain” of gas back onto the black hole triggers the next eruption.

The host galaxy of J1007+3540 is a massive elliptical galaxy with old stars formed 12 billion years ago. However, hidden behind a veil of dust, it is still churning out new stars at a high rate of over 100 solar masses per year. This suggests that even in this ancient, battered system, the cycle of birth and destruction is far from over.

The researchers plan to use even sharper X-ray eyes, like the Chandra Space Telescope, to map the hot gas around this system.

The new findings appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.