Nearly a third of the materials sent to New Brunswick landfills could be going to the compost pile instead.

That’s because a large part of the province doesn’t have a curbside compost collection program. And for the areas that do, waste sorting is difficult to enforce.

New Brunswick’s Department of Environment and Local Government is working toward a province-wide organics program. The Strategic Action Plan for Solid Waste aims to have a new program in place by 2028.

“A comprehensive organic waste program will help reduce emissions and conserve resources,” said a representative from the department in an email.

WATCH | Can New Brunswick agree on how to compost?

New Brunswick wants more residents composting through provincewide program

Each region now composts differently, and requirements vary widely depending on where you live.

In December 2025, the province conducted an online public consultation and it said it’ll be months before the results are released. The Department of Environment did not agree to an interview with CBC but said it also consulted Indigenous partners and environmental groups.

The department estimates about 30 per cent of all waste sent to the landfill is organic waste, such food, soiled paper products as well as yard and pet waste.

It’s proposing to install, through legislation, a 20 per cent cap on the amount of organic waste that can be disposed in regional landfills.

How does composting work right now?

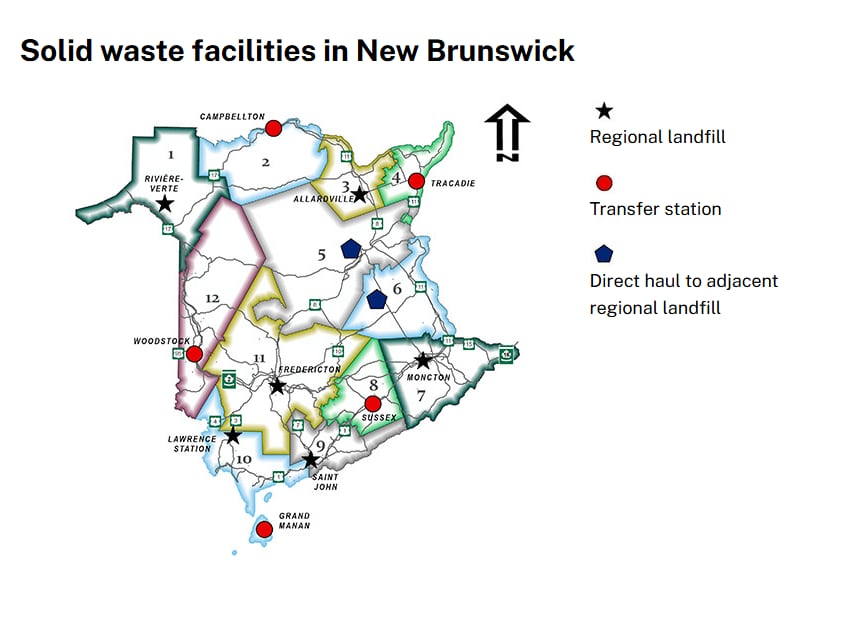

The province of New Brunswick is divided into 12 regional service commissions. Only four of those actually collect compost at the curbside: Southeast (Moncton area), Fundy (Saint John area), Kings (Sussex area) and Kent County.

The other regions — Capital (including Fredericton), Northwest, Restigouche, Chaleur, Acadian Peninsula, Miramichi, Southwest and Western Valley — don’t. And it would be pretty expensive to implement.

“When it comes down to it, it’s the financial aspect of having that implemented,” said Mélanie Rousselle, director of EcoDiversion with the Miramichi Regional Service Commission. “There is a lot of money that needs to go into that and the maintenance of it afterwards.”

She said it’s a cost that would end up being passed down to residents.

“If there is a cost associated for organics, then it would be tacked on to the property taxes or the taxes by the municipalities currently,” Rousselle said.

Mélanie Rousselle, director of EcoDiversion with the Miramichi Regional Service Commission, says it would cost a significant amount to implement curbside compost collection. (via Zoom)

Mélanie Rousselle, director of EcoDiversion with the Miramichi Regional Service Commission, says it would cost a significant amount to implement curbside compost collection. (via Zoom)

Other regions have similar reasoning.

“Introducing composting would require an additional collection stream, which would result in increased costs for municipalities, as well as significant infrastructure upgrades at our transfer station,” said a spokesperson with the Restigouche RSC.

Gary LeBlanc, director of solid waste management with the Acadian Peninsula RSC, said “it will not be a problem other than it will cost a lot.”

And even those that do collect curbside compost understand that the cost is significant.

“We speak from experience when saying collection contract costs are directly impacted by the number of separate streams a region collects,” said a spokesperson for the Kent RSC.

To make things more complicated, there are only six landfills in New Brunswick — other regions must pay to haul their waste to a transfer facility where it will be sorted and eventually sent to one of these six sites.

The province has six regional landfills, meaning all other Regional Service Commissions must either use a transfer station for sorting waste, or directly haul collected waste to another region. (Government of New Brunswick)

The province has six regional landfills, meaning all other Regional Service Commissions must either use a transfer station for sorting waste, or directly haul collected waste to another region. (Government of New Brunswick)

Miramichi completed a feasibility study in 2017 to determine whether it was worth implementing composting.

“Unfortunately because of the cost, and because we’re so split up and that we don’t have the facility in our area, because everything is direct-hauled to Red Pine [in Allardville], it was not feasible for us to do that,” said Rousselle.

Instead, Miramichi, like other regions without curbside compost collection, encourages residents to take up backyard composting.

“We provide units sold at reduced cost throughout the year, and when residents attend our composting workshops they’re half price. So we’re pretty much giving them away,” Rousselle said, noting they’ve sold about 1,000 at-home compost systems in the past 15 years or so of the program.

“We want to make sure that there’s no barriers for residents to purchase these items.”

Making composting easy

Making composting easier for residents is one way municipalities increase uptake. But another is enforcing it.

Saint John started curbside composting in 2001. But in 2022, the city restricted homes to two garbage bags per week and residents began filling their compost bins instead.

“We saw a 25 per cent increase in the amount of compost people were putting out,” said Tim O’Reilly, the city’s director of public works director. “So it’s surmised to assume that people were putting more compost into the garbage stream prior to implementation of that program.”

Tim O’Reilly, director of public works for the City of Saint John, said residents drastically increased the amount of compost they sorted after a limit was placed on the number of garbage bags they could put curbside. (via Zoom)

Tim O’Reilly, director of public works for the City of Saint John, said residents drastically increased the amount of compost they sorted after a limit was placed on the number of garbage bags they could put curbside. (via Zoom)

O’Reilly said the change increased what Saint John is composting from 3,000 to 4,000 tonnes per year. And the city is actually saving money in the process, said O’Reilly.

“Compost costs about a third of the cost of sending garbage to the landfill. Because when you think about it, when you send garbage to a landfill, it has to be stored essentially forever,” he said. “We’re saving over $200,000 per year in tipping fees as a result of our residents composting more and recycling more.”

Moncton also has a curbside program, using green bags instead of bins. Those bags are collected and sent to the Eco360 landfill in Berry Mills, 15 kilometres northwest of the city, which received 24,000 tonnes of compost in 2025.

Janet Lee Hale, compost facility operations manager at Eco360, said she sometimes there is contamination of garbage items in the compost, and vice versa.

Janet Lee Hale, the compost facility operations manager at Eco360, said if a load of compost is too contaminated, it will end up in the landfill. (Victoria Walton/CBC)

Janet Lee Hale, the compost facility operations manager at Eco360, said if a load of compost is too contaminated, it will end up in the landfill. (Victoria Walton/CBC)

“If a significant portion of the load is contaminated, we do have to reject,” she said.

Hale said diverting more compost from the landfill pile “would save room in our landfill … for generations to come.”

Preventing compost from being landfilled also has environmental benefits.

“When you trap organics within a landfill, it produces a lot of methane gas, which is bad for the environment,” said O’Reilly.

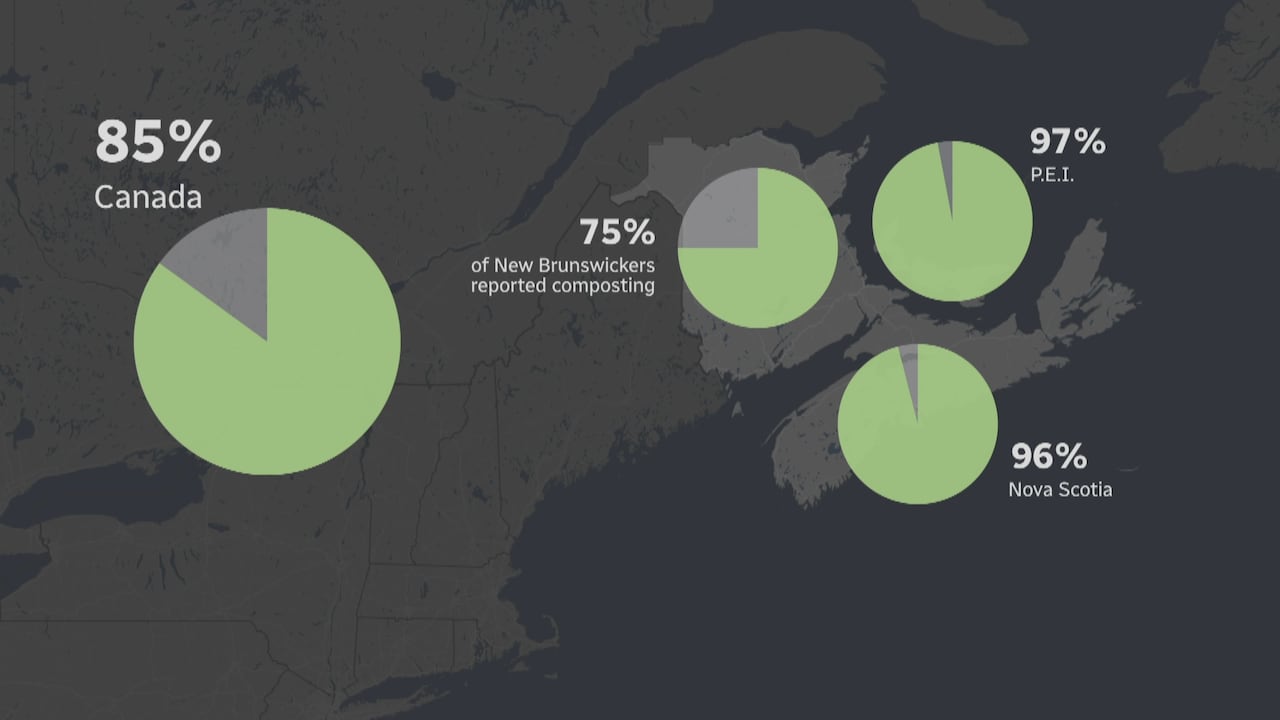

And while Hale said things are improving with time, New Brunswick is still behind when compared to other provinces. Just 75 per cent of New Brunswickers self-reported composting to Statistics Canada in 2023, compared with 97 per cent of P.E.I. residents and 96 per cent of Nova Scotians. The national average is 85 per cent.

New Brunswick is lagging behind the national average and the other Atlantic provinces when it comes to how many people report they compost. (CBC News)

New Brunswick is lagging behind the national average and the other Atlantic provinces when it comes to how many people report they compost. (CBC News)

Hale said while it may be a while before all regions in the province have implemented curbside collection, things are moving in the right direction.

“There’s always room for improvement, but I do feel like the public is doing a great job,” she said. “Year after year we’re seeing more and more organics going into the green bag, and I genuinely think people care in our community and they want to do better.”

As for the province’s timeline, its strategic plan indicates the proposal for a province-wide organics program was originally supposed to be presented to government in fall 2025, but it hasn’t happened yet.