Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Focus Features, Netflix, Paramount, Samuel Goldwyn Films, Sony Pictures, Everett Collection

In Noah Baumbach’s 2007 movie Margot at the Wedding, Jack Black’s character, a would-be painter, former musician, and general layabout named Malcolm, is accused by his fiancée of being competitive with everyone. “It doesn’t even matter if they do the same thing as you,” she says. “He’s competitive with Bono.” Malcolm concedes the point, explaining, “I don’t subscribe to the credo that there’s enough room for everyone to be successful. I think there are only a few spots available” — and people like Bono are taking them up. The implication is that, were it not for the tragic injustice of the limited-spots situation, Malcolm would be recognized for being as talented, if not more, than the lead singer of one of the biggest rock bands in the world.

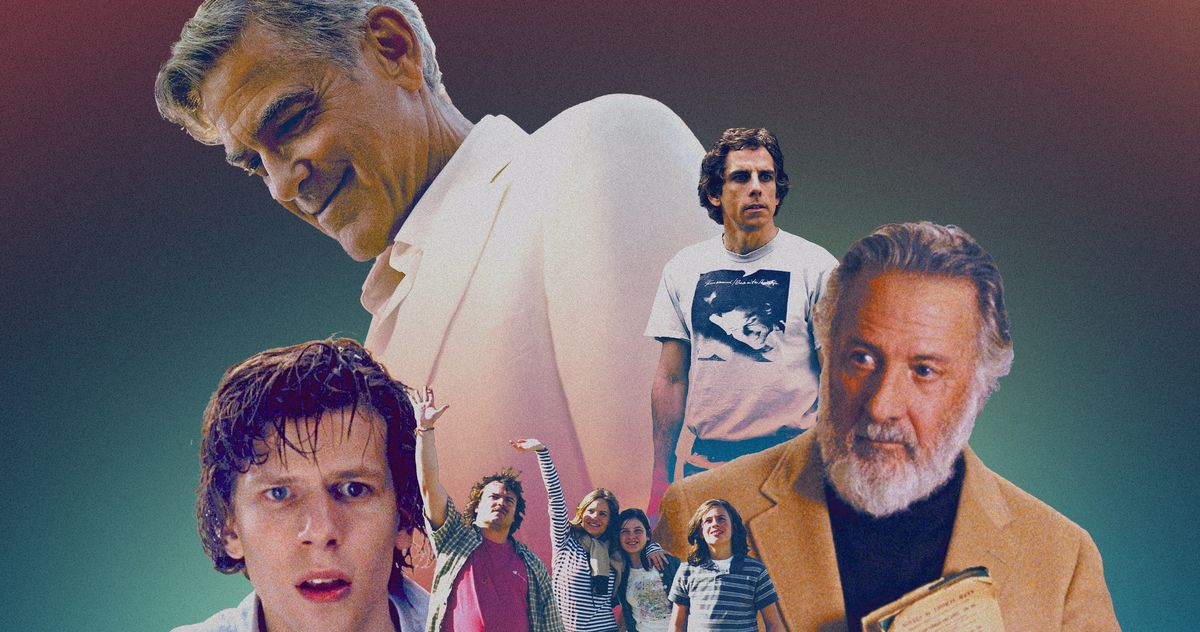

Malcolm is a typical Baumbach character: delusional and ludicrously self-important, yet not totally wrong either. (Who has not heard Bono speak and thought, Why him?) Others cut in the same mold include Walt Berkman (Jesse Eisenberg) from 2005’s The Squid and the Whale, a teenager who rationalizes his plagiarizing of a Pink Floyd song by saying, “I felt I could have written it”; Roger Greenberg (played by frequent Baumbach collaborator Ben Stiller) of 2010’s Greenberg, a middle-aged misanthrope living in the long aftermath of a ruinous decision in his youth to turn down a major record deal because it wasn’t good enough for him; Josh Srebnick (Stiller) of 2014’s While We’re Young, a struggling filmmaker who has toiled for years on a dull documentary about “how power works in America”; and Harold Meyerowitz (Dustin Hoffman) of 2017’s The Meyerowitz Stories, an elderly sculptor blaming his obscurity on the shallow philistinism of the art world: “I think I would have had greater success if I’d been more fashionable.”

These are men at every stage of life who resent the world for not recognizing their genius. The older ones are haunted by forks in the road where the path not taken surely would have led to the success they both feel they deserve and desperately desire. Their narcissism is not tempered with a single drop of humility, but rather with oceans of self-loathing that are then channeled outward, in scalding torrents, at their friends and family. They construct elaborate justifications for their selfish and cruel behavior, while insisting that they themselves have been overlooked and misunderstood. They are in a permanent state of arrested development (“I haven’t had that thing yet where you realize you’re not the most important person in the world,” Malcolm says), their massive egotism undermined by deficiencies in the basic skills of living, like knowing how to cook or drive or swim.

These men are also fathers and sons, the horrific dad being a mainstay of the Baumbach canon. The archetype is Jeff Daniels’s Bernard Berkman from The Squid and The Whale, a has-been writer who instills in Eisenberg’s Walt a monstrous sense of superiority through a million high-handed pronouncements and snap judgments: dismissing A Tale of Two Cities as “minor Dickens,” insinuating that Walt’s girlfriend isn’t hot enough for him. Bernard is reprised in Hoffman’s Harold Meyerowitz, who is aggressively uninterested in his children’s lives, their only purpose being to serve as minor satellites that reflect his glory back onto him. His son Matthew, also played by Stiller, makes a lot of money as a financial adviser, but unfortunately, the only sort of success that matters in Baumbach’s universe is artistic in nature. “I beat you! I beat you!” Matthew screams at his father in one scene as Harold drives away, obstinately deaf to his son’s claims, aloof to his very existence.

I have made this taxonomy of the Baumbach male because the curious thing about his latest movie, Jay Kelly, is that this distinctive creature barely features in it. Jay Kelly is Baumbach’s most nakedly award-aspiring film to date, a starry tribute to the magic of the movies that seemed to be an Oscars contender before joining Wicked: For Good in the ignominious club of hopefuls that got zero nominations. There will be no gold statuettes to compensate for the fact that Jay Kelly is also one of Baumbach’s weakest offerings, verging on the maudlin and containing few of the ingredients that made his body of work so beloved by those who queasily saw something of themselves in his loathsome, exasperating men. The Baumbach male appears here as a mere echo, a figure of diminishing interest who serves to punctuate the director’s new concerns and obsession: becoming an artist who identifies more with the Bonos of the world than the Malcolms.

If Baumbach, 56, is one of the preeminent chroniclers of white Generation X, from the 1980s adolescent experience of The Squid and the Whale to the midlife crises of While We’re Young and 2019’s Marriage Story, then Jay Kelly is his late-middle-age movie, preoccupied with the looming shadow of death. George Clooney plays the titular character, a Hollywood star in his 60s who, like Clooney himself, is heir to the classic leading men of old: Gene Kelly, Gary Cooper, Cary Grant. His sun-kissed existence is disturbed by a series of overlapping events: his youngest daughter, Daisy, flying the coop to college; the death of his mentor; and, most fatefully, a run-in with an old acting-school friend, Tim, who flamed out of the business long ago, while Jay’s career soared into the stratosphere.

Jay is worried that the Jay onscreen is just a persona, a vaporous construct built from the projections of fame and the machinery of Hollywood, as thin as the sets where he spends much of his time. “Is there a person in there?” Tim asks him after they have one too many drinks at the bar. “Maybe you don’t actually exist.” Free from fame’s distorting prism, Tim definitely exists, in all his inconsequential glory, and is awfully bitter about it, especially since he holds Jay responsible for nabbing a role that would have sent him on his merry way to stardom. Tim, played with coiled resentment by Billy Crudup, is the closest thing the movie has to a quintessential Baumbachian frustrated artist, and at first, it seems like the movie is going to tantalizingly play as a duel between these opposing representatives of failure and success, the two poles of Baumbach’s world. When Jay muses about remembering the man he once was, Tim shoots back, “I don’t think you want to meet that guy again.” He holds in contempt the young Jay for stealing his shot at fame as well as the old Jay for looking back fondly at a time when he was a nobody — which, of course, is one of the privileges of being a somebody.

This would seem to offer Baumbach fertile thematic ground, another of his forks in the road, the decisive moment that determines his characters’ future happiness and self-esteem — their entire identity, actually, according to their own pitiless scorecard for measuring a life’s worth. Instead, the confrontation with Tim sends Jay on a picturesque trip through France and Italy, chasing after some quality father-daughter time with Daisy. She and her friends are spending their last summer before college doing typical young people things — charging stuff to their parents’ credit cards, staying in cheap hostels, hooking up with European strangers — and naturally, she doesn’t want her father around. So Jay is left to hang with an entourage that includes his publicist, Liz (Laura Dern), and his manager, Ron (a criminally underutilized Adam Sandler), as Jay take selfies with starstruck travelers and makes his way to a film festival in Tuscany where he is to be presented with a tribute for his work. Along the way, he revisits scenes from his life.

Not a lot happens on this journey. There is an aimless and ultimately aborted subplot about a past romance between Liz and Ron. Jay thwarts a robbery and reluctantly becomes a tabloid hero — more grist for the nagging feeling that his life isn’t real. He confronts his eldest daughter, Jessica, in flashback as she accuses him of choosing his career over their family. Jay’s ostentatious success confounds Baumbach’s usual parental dynamics, which revolve around megalomaniacal patriarchs unleashing their psychological traumas on their poor kids. Jay’s absence as a dad seems like a blessing compared to the ever-present shadow Baumbach’s other fathers cast on their children. (Take Bernard Berkman’s insistence on “my night” in his custody battles with his ex-wife, Joan, which are less expressions of filial affection than pathetic attempts to have people around he can easily dominate.) Jay’s time in Tuscany includes a detour in which he confronts his own neglectful father, but Kelly père exhibits little of the venom that characterizes Baumbach’s usual bad dads.

In the end Jay is abandoned by everyone but Ron, his faithful Sancho Panza, and left to wonder whether his career and his life amount to anything at all. (Spoiler alert: He realizes that they do.) The film clearly takes inspiration from 8 ½, Federico Fellini’s masterpiece of self-reproach and self-doubt, but it perhaps more closely resembles the Love Actually plotline that sees Bill Nighy realize his dowdy manager is the love of his life. The only reason Jay Kelly is not a disaster is the presence of Clooney, who is about as interesting an icon of fame as you can get, giving it a modicum of pathos and a lot of allure. At 64, he is nearly as handsome as ever, making even Crudup seem a tad pedestrian in comparison. What Clooney can’t do, even if he had been asked to try, is convey what it is like to fail, to be stuck for your entire life with a version of yourself that is unnoticed and unadmired — what it is like, in other words, to be most people.

Baumbach has argued that there is consistency across his films. “A lot of my movies are about people who self-identify as a failure because the lack of success, to them, has equaled failure, which is not the case,” he recently told the New York Times. “But defining yourself by your success does the same thing: It’s just another way to not look at yourself as who you might actually be. That’s definitely the case for Jay.”

I’m not sure I buy that there’s such an equivalence. (For one, whatever illusions come with success are far less corrosive to the soul than those that accompany failure.) It’s also clear some deeper change has taken place in Baumbach’s movies, starting with Marriage Story. Baumbach’s previous avatars onscreen had been Eisenberg and Stiller, playing awkward, painfully insecure characters who seemed to be crawling out of their skin. Then he became Adam Driver: tall, handsome, exuding importance. Driver plays a theater director so acclaimed that he scores a MacArthur “genius” grant, the kind of award a classic Baumbach character would have deranged fantasies about winning. The movie opens with his soon-to-be-ex-wife enumerating, in a letter to their therapist, all the ways he’s a good father: “It’s almost annoying how much he likes it, but it’s mostly nice.” That was new.

Although Baumbach’s movies are not strictly autobiographical, they are obviously informed by his life. The messy divorce of his parents is the inspiration for The Squid and the Whale, while his separation from Jennifer Jason Leigh forms the contextual background of Marriage Story. Baumbach’s own father, the writer Jonathan Baumbach, died in 2019, a couple of years after The Meyerowitz Stories, which showed that even adults still need their fathers — still crave their attention, approval, and respect — and still can be hurt by them. It is no great stretch of the imagination to surmise that he has more than a little in common with the disgruntled men who believe the world has unfairly passed them over; as he once told the Times, The Squid and the Whale, which followed an eight-year dry spell in his directorial career, “makes me very emotional, because it reminds me of the time I was writing it and feeling like it was my last chance after having struggled for a bit.” I’d further posit that bearing a grudge against the universe and believing you’re an unrecognized genius, the fundamental qualities of the Baumbach male, might be necessary for making valuable works of art. That a little delusion and rage are required to keep the demons of complacency away.

Being a father himself (he has two young boys with his partner, Greta Gerwig, as well as an older child with Leigh) seems to have softened Baumbach. “I cry a lot now,” he recently told GQ. “I find a lot of life emotional in a good way.” His professional collaborations with Gerwig produced Frances Ha and Barbie, both of which are markedly more buoyant than Baumbach’s early work. Marriage Story was followed by White Noise, a $100 million adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel that lurched in a totally different direction, a bewildering misfire that suggested Baumbach wasn’t quite sure what to do with himself and was casting about for inspiration from literature. Jay Kelly feels like Baumbach stepping through the mirror, peering back at his world through the lens of age and enviable accomplishment.

So what happens when your ego is satisfied, when your innermost vision of yourself is validated by the outer world? Marriage Story is not one of his best movies, but it shows that Baumbach can evolve and take risks that mostly pay off. I am thinking in particular of a scene toward the end in which Driver sings “Being Alive” at a bar in front of the members of his theater company. His character is a little drunk and feeling sentimental, a common scenario for singing along to Sondheim, and it has the potential to be deeply embarrassing. But the scene works, both weird enough to be interesting and a straightforward appeal, via Sondheim’s transportive wizardry, to the biggest emotions: love, regret, the terror of being alone. At that moment, Driver resembles Baumbach’s unlovable losers, whose grandiose conceits ultimately burn away in the harsh light of reality, forcing them to “embrace the life you never planned on,” as one character puts it in Greenberg, a life that you feel is beneath you. Here’s hoping Baumbach hasn’t forgotten that feeling.