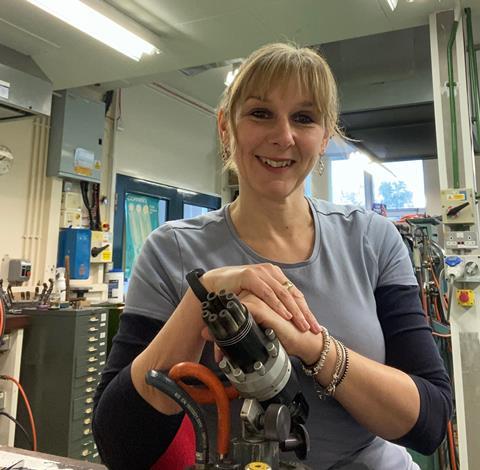

For Abigail Mortimer a career in glassblowing started not with an interest in science, but in ceramics. As a child she did pottery at school and later completed an art foundation course before studying glass, architectural glass and ceramics at Sunderland University, UK. It was here that her interest in glass blowing was sparked.

‘I think the main thing for me is that I wanted a practical job. I knew that I would not be able to sit behind a desk all day.’ She took on a role as a trainee milliner, before seeing an advertisement for a trainee scientific glassblower at the University of York. She’s still there 17 years later.

Today Mortimer is the only scientific glassblower at the university, a role that is becoming increasingly scarce in the UK due to factors that include an ageing workforce, financial pressures on universities and outsourcing to external companies. According to the British Society of Scientific Glassblowers there are probably less than 18 UK universities with glassblowing departments.

At York, Mortimer’s main job is to support teaching and research across the university. Around 90% of her work is for the chemistry department, and she is very much in demand.

‘My role is to help design and manufacture bespoke glassware that is specific to research and teaching,’ she says. As well as creating bespoke pieces, Mortimer also makes standard items such as columns, ampoules, Schlenk tubes, Schlenk lines and manifolds, and repairs glassware that breaks. The university has said that ‘every undergraduate passing through York Chemistry Department has used something either made or fixed by Abby’.

Collborative problem solving

For Mortimer no day in the workshop is the same. Her job is incredibly reactive – someone might come in with a repair that needs addressing, while another might need help designing a piece for a new experiment. ‘I have to try and balance it all to fit in emergencies and try and hit everybody’s deadlines.’

Designing glassware for experiments is a real collaboration between glassblower and scientist. ‘I don’t have the chemistry background… so I rely on them a lot to tell me about the chemistry and then I can help provide a solution.’ Most of the time a researcher will come to Mortimer with an idea or a sketch of what they need, which she will talk through to find the best solution.

This ability to help scientists solve problems is what gives Mortimer the most satisfaction in her job. ‘You can provide something that you can’t buy and solve that problem for researchers or for teaching,’ she says. While that could involve making a complex piece of glassware, sometimes the solution is surprisingly simple. ‘In a way, sometimes that’s even more satisfying because they go, “Oh, my God, that just works so well.” We did something that’s really quick and easy, but they couldn’t have bought that anywhere.’

In the UK there is no official course or route into scientific glassblowing – like Mortimer many glassblowers apply for a role and are trained in-house. Mortimer joined the University of York in 2008, spending four years following a syllabus from the British Society of Scientific Glassblowers, at which point she had learnt the basic skills required to be a competent glassblower. In 2014 her boss retired: ‘I’ve run the workshop ever since, for the past 11 years.’

Valued teaching and research support

When asked if there is anything she can’t do Mortimer laughs: ‘Yes, of course! But I can do most things requested by the department.’ Changing scientific practices also play a role. ‘When I was training, I didn’t do a lot of quartz work,’ she says. However, over the past few years more of these requests have come in. Much of her ongoing training is self-motivated – reading up on new practices, contacting other glassblowers for practical advice and practicing new techniques.

While technicians like Mortimer underpin the scientific research within a university they can often remain hidden. To this end Mortimer has been part of the Technician Commitment delivery group, an initiative that aims to improve the visibility, recognition, career development and sustainability of technicians working in higher education and research.

‘I think a lot of technicians just kind of crack on and get on with our job,’ she says. ‘But really, we are doing so much in the background to help drive teaching or research.’

At York, Mortimer feels her unique skills and contributions are appreciated. ‘I think because the skill is less common now, I feel like the department and the university appreciate the fact that we do have this service here and it is valued,’ she says.

And after 17 years, glassblowing has still not lost its appeal. ‘It’s always challenging. It’s never really boring… and it is a lot of fun,’ says Mortimer. ‘I really love my job.’