This year’s winner of the Washington State Book Award for Creative Nonfiction is a breathtaking achievement of memoir, art and Chinese history.

Growing up, Tessa Hulls knew three things about her grandma, Sun Yi: She was from China, she was a writer, she was crazy. Their home was defined by Sun Yi’s fragile mental state and the toll it took on Tessa’s mom. Alone in her room, Sun Yi scribbled disjointed memories and anxiously awaited the return of her daughter, the only person in her family who could read or speak Chinese.

Tessa’s mom believed that Sun Yi’s madness and writerly temperament could be inherited, and feared that danger was lurking in the mind of her own creative daughter.

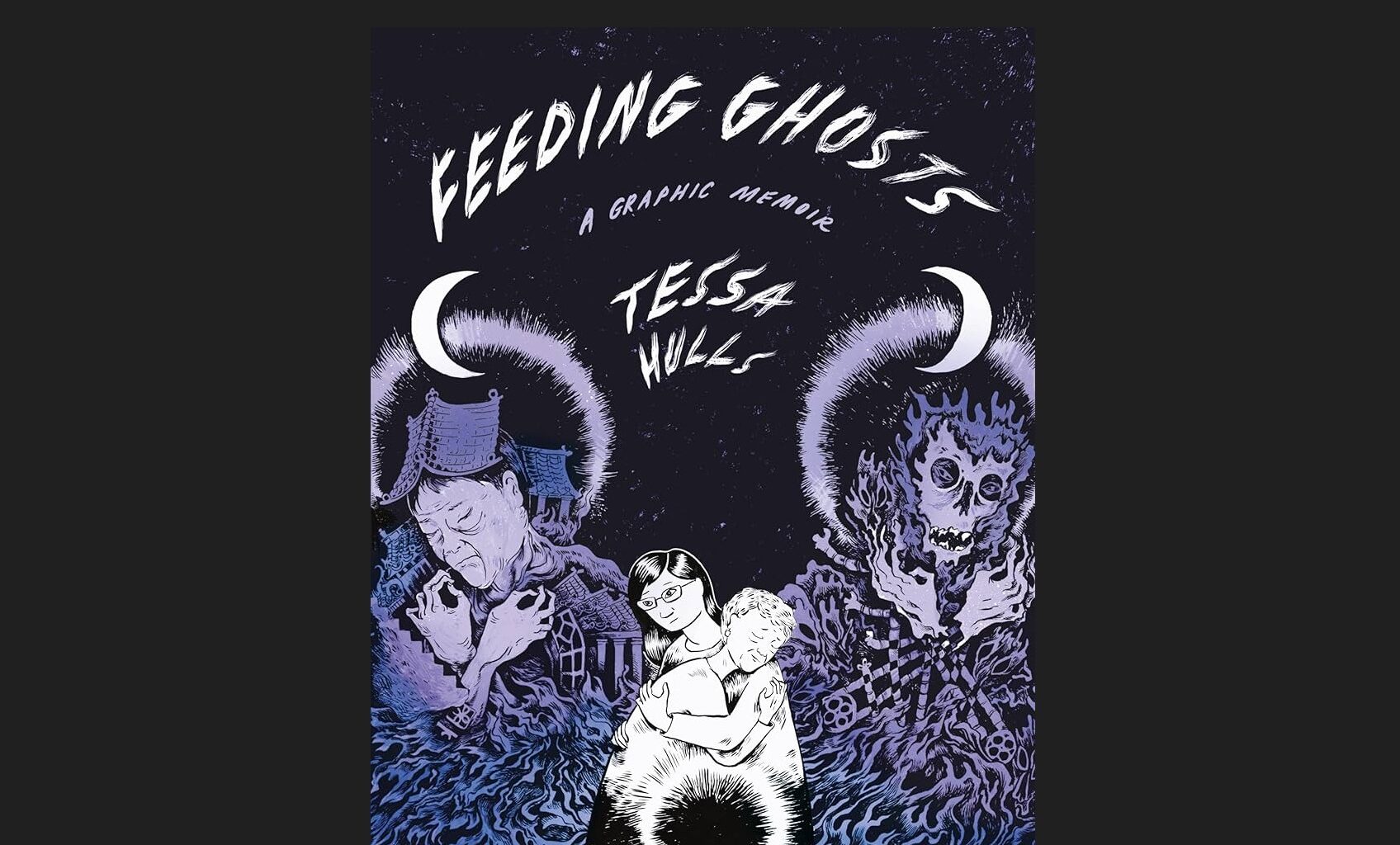

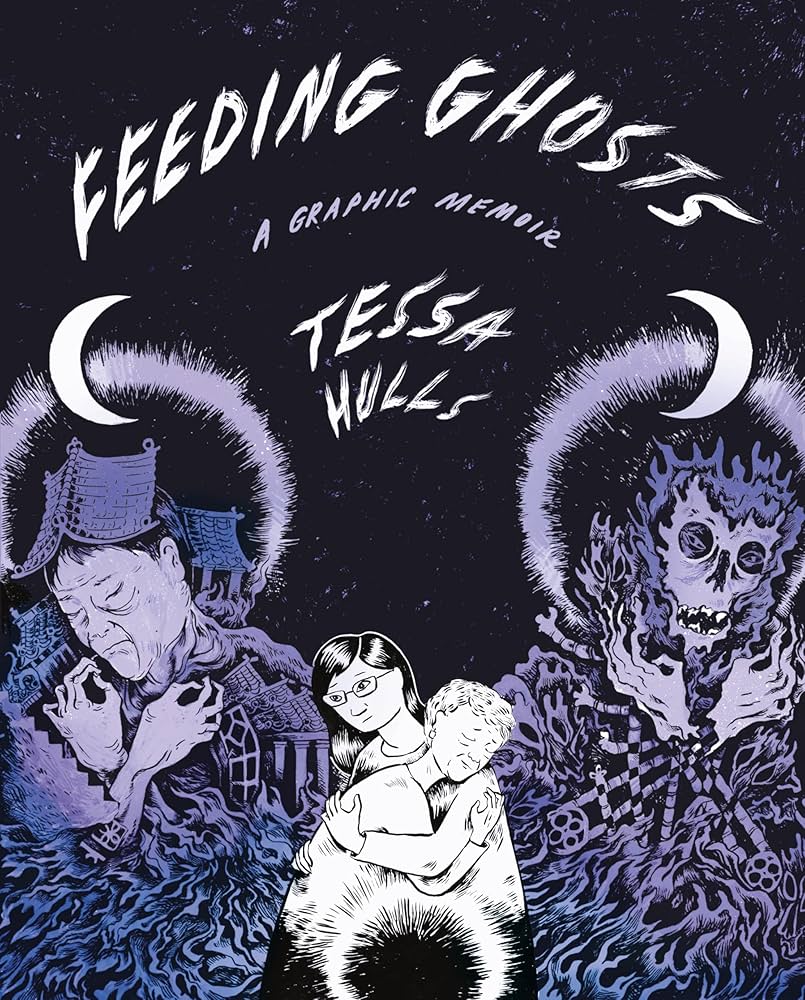

Alternately distant and emotionally suffocating, her mom’s psychic wounds manifested in an unpredictable dual nature that Hulls calls the “ghost twin.” For the first time, we see the imagery that Hulls uses throughout “Feeding Ghosts: A Graphic Memoir” to represent the trauma that haunts her family: spectral swirls that feel both delicate and frenetic crowd into the panels’ negative space.

“Feeding Ghosts: A Graphic Memoir” tells its story with powerful visual metaphors. (Photo courtesy of Tessa Hulls)

“Feeding Ghosts: A Graphic Memoir” tells its story with powerful visual metaphors. (Photo courtesy of Tessa Hulls)

To escape her mom’s love/anxiety, Tessa escapes into a nomadic life of art and seasonal work. But even cowboys can’t drift forever, and Tessa’s journey back to her mother begins with the question: “What broke my family?”

Starting with her grandma’s memoir, she uncovers a story of intertwined insanities: Sun Yi’s mental collapse, brought on by the insanity of life under Maoist regime. Hulls lets her grandmother speak for herself in this part of the story, using a typewriter font to denote words drawn from her memoir: “Eight Years in Red Shanghai: Love, Starvation, and Persecution.”

In 1949, Sun Yi worked as a journalist in Shanghai when the People’s Liberation Army took the city. She resisted assignments to write propaganda and became a target of Mao’s crackdown on “ideologically problematic people.”

The line between her grandma’s lifelong paranoia and the psychological torture she endured — constant surveillance, interrogation, being forced to rewrite the same confession over and over — is a straight one. But Sun Yi’s story doesn’t end with her memoir, and Tessa and her mom have origin stories of their own.

In the nine years she spends researching, writing and illustrating this book, Hulls unearths a sweeping family saga contoured by the powers of war, colonialism and totalitarian government. Hulls’ candid narration and evocative illustrations make a complex period of Chinese history feel immersive and accessible.

Tessa Hulls is an artist, writer and adventurer “whose restlessness has carried her to all seven continents.” (Photo courtesy of Gritchelle Fallesgon)

Tessa Hulls is an artist, writer and adventurer “whose restlessness has carried her to all seven continents.” (Photo courtesy of Gritchelle Fallesgon)

Hulls’ etching-like illustrations of material objects and places — a single shoe, a coal-burning stove — keep us grounded in reality, but Hulls’ true gift is for powerful visual metaphors. Most striking are the ghosts, wearing a myriad of forms that link her family history with China’s descent into dictatorship.

Phantom feathers represent the sparrows killed in Mao’s 1958 eradication campaign, a man-made omen of famine. Turn the page, and petals from Mao’s Hundred Flowers Campaign turn into the heads and limbs of executed dissenters.

“Feeding Ghosts” is the second graphic novel to win a Pulitzer; “Maus” was the first. Like Art Spiegelman, Hulls didn’t merely create a visual and literary masterpiece, but a masterclass in media literacy. At its heart, “Feeding Ghosts” is about the stories we tell ourselves to maintain a mythos. What do we feed hungry ghosts if not the lies we choose to believe? During a time when censorship and the sanitization of history are making a resurgence, “Feeding Ghosts” compels us to embrace our complexity.

Emma Radosevich is a collection development librarian at Whatcom County Library System. Visit us at wcls.org.