The fence of the title isn’t a terribly imposing one: a utilitarian, standard-issue wire border, easy bent or broken down, and affording no protection from outside eyes. But it’s the heaviest symbol of many in Claire Denis‘s stripped-back, forthright new film, a barrier between haves and have-nots that proves as fixed and obdurate as the two men on either side of it, and the tensely opposed societies they stand for. On the inside are the outsiders, white western interlopers making would-be intruders of those whose land they’ve stepped on and built on — “a construction site in West Africa,” as an opening title card simply declares. Many things are simple in “The Fence,” an unusually sharp-cornered and rhetorical work from this typically elliptical and sensuous filmmaker, but the rage swelling beneath its still, mannered surface is not.

As much as “The Fence” represents a departure for the director in some senses — it’s her first stage adaptation, for one thing, and makes scant attempt to conceal those roots — in others it’s a kind of homecoming. For the first time since 2009’s immaculate “White Material,” Denis returns to the continent that shaped her childhood — as the daughter of a French civil servant stationed in multiple West African territories — and is woven through her filmography, from the barbed colonialist nostalgia of her first feature “Chocolat” through the revisionist Foreign Legion fever dream of “Beau Travail.” And she returns, too, to the redoubtable Ivorian actor Isaach de Bankolé, a recurring presence in her oeuvre from her debut, whose potent signature minimalism as a performer lends “The Fence” both its humanity and its disquieting mystery.

We’re in the same contemporary, unidentified postcolonial terrain as “White Material,” albeit a flatter, thirstier stretch of it, where white settlers or developers have outstayed a welcome that was never really extended to them in the first place. A lengthy, frictional holding pattern is bristling into something more violent, though the fence stands for now. It surrounds a private construction site — of unclear purpose, beyond lining western pockets — presided over by jaded American foreman Horn (Matt Dillon) with his deputy, hot-headed British engineering graduate Cal (Tom Blyth), and manned by local villagers of understandably doubtful allegiance.

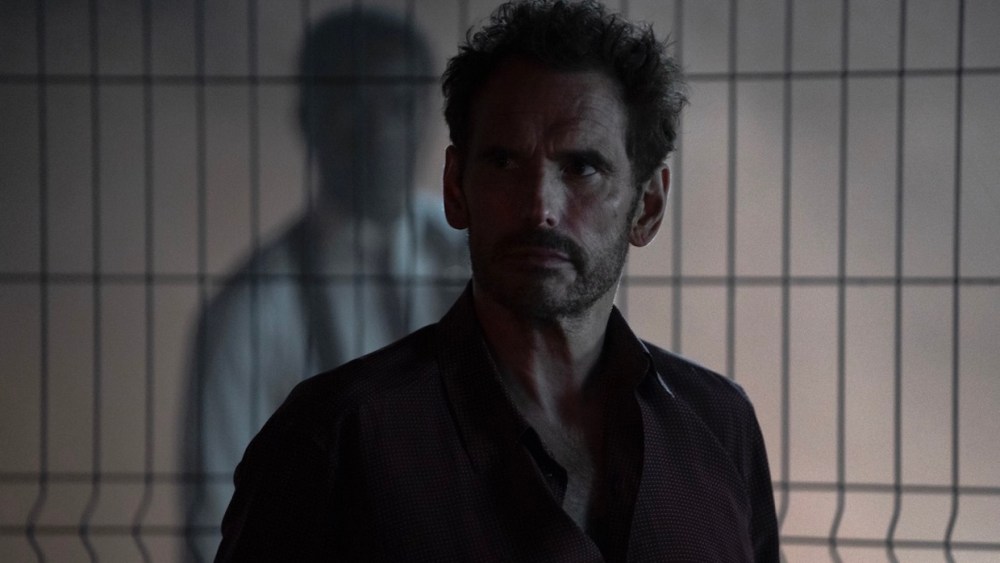

At the outset of a tightly contained narrative that spans under 24 hours, one of these workers has just been killed, in what Horn claims was an unfortunate site accident. That evening, the dead man’s brother Alboury (de Bankolé) shows up to collect the body and take it home. It’s a simple request that Horn is suspiciously loath to grant, instead glibly inviting Alboury inside the compound for a conciliatory drink. He’s politely but firmly refused by the visitor — soberly and a bit surreally dressed in a pristine chalkstripe suit courtesy of producing partners Saint Laurent — who announces his intention to stand implacably on his side of the fence until his demands are met. One man will not be moved physically, the other not emotionally; de Bankolé’s soft, stoic poise and Dillon’s gruff, spiraling bluster are likewise at odds.

It’s a stark standoff, rife with unspoken accusations and hostilities, that could stand allegorically for any number of racial injustices and inequalities still lingering from the days of colonial occupation. Denis’ script, co-written with Andrew Litvack and Suzanne Lindon, is adapted from “Black Battles With Dogs,” a 1979 play by Frenchman Bernard-Marie Koltès, and notwithstanding the presence of a smartphone (neutered by a lack of signal), the film could be set at more or less any point in the last half-century: Whatever foul play has occurred here feels the result of a deeply entrenched spirit of western entitlement. (Cal is introduced singing along to “Beds are Burning,” the indigenous land rights anthem by Australian rockers Midnight Oil, as he speeds recklessly across the veld in his pickup truck — not one of Denis’s subtler needle-drops, though the resonance seems lost on him.)

Presented by Denis, DP Eric Gautier and editor Guy Lecorne as a measured, dimly lit shot-reverse-shot volley, the two men’s mutually unyielding conversation is blatantly stage-rooted, but also a strangely compelling psychological stalemate. Denis doesn’t seem entirely at home with material this rigidly verbal, and the performances in turn are sometimes uncertainly directed — Dillon, while an aptly foreign presence in this severe environment, sometimes seems even more out of place than Horn is supposed to, adrift in a sea of heavily written dialogue.

Yet a countering, volatile dynamism in the film comes from rising Brit stars Blyth and Mia McKenna-Bruce, both excellent, with the latter surprisingly but most effectively cast as Horn’s ill-matched, far younger new bride Leonie. Fresh off the plane from London in hopeless strappy heels, and unprepared for the tacit battleground she’s stumbled into, she’s set in combat mode early by the boorish, hard-drinking Cal when he picks her up from the local airfield and instantly antagonizes her.

But we sense testy desire there too, charging and complicating this otherwise austere setup and combining uneasily with what may or may not be inchoate queer signals elsewhere. Suddenly, then, we’re in more familiarly febrile Denis terrain, and while the expected woozy score by her longtime collaborators Tindersticks may only kick in very late in these hushed, echoey proceedings, no other filmmaker could wring more cinematic sweat out of Kylie Minogue’s droning nu-disco hit “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head,” floating between rooms from a tinny portable speaker.

Both something old from her and something a bit new, “The Fence” isn’t a major Denis work: Its gear changes from arch, theatrical parable to supple mood piece aren’t smooth ones. But it gnaws steadily away at you, like that Kylie earworm, only to graver effect. “It’s so unreal here,” Leonie says, only a few hours into her African odyssey, her gaze still misted with an outsider’s fear and reverie. “It’s very real, you’ll see,” Cal corrects her. “The Fence,” conscious of its own intrusive perspective, is occasionally distracted by the sensual world — but mostly seeks to bluntly deromanticize all that heat and dust.