Giorgio Armani, the revolutionary designer who made his indelible mark on both fashion and interior design throughout his 50-year career, has died at the age of 91, his eponymous company announced on September 4, 2025. The billionaire businessman, who retained sole ownership of his company, was born on July 11, 1934, in Piacenza, Italy. Though it’s hard to imagine now, Armani’s career had humble origins: he got his start in fashion as a window dresser at a department store. In 1975, he founded his luxury fashion house in Milan. The aesthete, who was known for his obsessive attention to detail, forever changed the silhouette of office fashion when he introduced his designs for unstructured yet sumptuous suits for both men and women, popularized in the 1980 film American Gigolo, which featured actor Richard Gere dressed in head-to-toe Armani. His clothing was featured in many iconic films and television shows that followed, including The Untouchables and Miami Vice. His designs quickly became a celebrity staple on the red carpet too.

In 2000, Armani launched his interior design brand, Armani/Casa. As with his clothing, Armani favored simple yet elegant designs that emphasized practicality and a human presence in his interiors. “A home is a nest, where the most important thing is not the surroundings, but who lives there,” the designer told Architectural Digest in a 1983 tour of his home in Forte dei Marmi, Italy. “I never want to feel like an object in my own home,” he added, directly comparing his restrained design philosophy to that of his fashion sensibilities. “Interior design is something like putting on a comfortable, unstructured jacket.”

Throughout the years, Armani opened the doors of his many self-designed spaces to AD, from a 17th-century home in Switzerland laden with dark mahogany to a Far East–inspired Saint-Tropez abode. “I have fun with my homes, which have been my greatest investments. I don’t buy Picassos, I buy houses,” he said in 2015. “This is a passion I’ve had since I was young—creating ambiences that make you want to stay.” — Katie Schultz

In 2004, Architectural Digest revisited Armani’s Forte dei Marmi farmhouse, speaking with the designer about how the home had remained unchanged and about his design philosophy.

Reread the article from the December 2004 issue below.

Giorgio Armani, the designer whose creations are at the same time classic and revolutionary, represents a paradox in the world of fashion. The couturier, who eased the tailored fit of traditional clothes by inventing a relaxed, unstructured look paired with a comfortable feel, nonetheless remains a classicist, searching for an ideal of beauty by avoiding the unnecessary. Through a process of elimination, he reduces designs to elemental simplicity, producing trend-resistant pieces that never fall out of fashion.

Though Armani is best known for his sartorial innovations, he has long experimented with interiors. His calming eye easily moves between fashion design and interior design, underscoring the close, sometimes intimate, relationship between the two disciplines. For Armani, interior design starts in the home—specifically, his home, or homes, in Europe and America. His own interiors showcase forerunners of the furniture in his line Armani Casa, and the restraint of the forms that characterize pieces now on his showroom floors was evident in a house he designed in the early 1980s in Forte dei Marmi, a retreat on the Versilia coast in Tuscany (see Architectural Digest, May 1983). Some 20 years later the interior remains timeless. “The house in Forte was my first holiday home and, therefore, holds a special place in my heart,” says the designer. “I decided to decorate it with the idea of creating a cabin on the sea. I have not changed the house since then, and it has lived incredibly well over the years.”

Though Armani is best known for his sartorial innovations, he has long experimented with interiors.

COPYRIGHT ©2003 THE CONDÉ NAST PUBLICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Italy is blessed with traditional farmhouses that have acquired a second lease on life as vacation and weekend homes. But these charmingly casual houses, many of them centuries old, come with a rigid spatial order that is antithetical to modern lifestyles. Made of stone, the interior walls form boxy configurations that are difficult to adapt to the lives of people who want ease of movement. The farmhouse that Armani found in Forte dei Marmi, a long-established resort community convenient to Milan, had already been restored in 1940, but Armani completely reinvented the interior, opening it for flow.

Just as he relaxes the structure of clothing, he relaxed the house’s structured interiors. The exterior was left largely as he found it, a beautifully proportioned, rustic two-story building comfortably settled on its grounds, but he brought down walls inside. Rooms lost their boundaries and merged into larger spaces that run through and up the house. The apparently simple farmhouse masks a far more complex—and modernist—interior world.

Armani may be an inspired designer, but the inspirations are based on principle—the principle of function: If his fashions are eminently wearable, his interiors are equally livable. He believes that a house should conform to its occupant and not the occupant to the house. “In essence, a house should not overwhelm the person living in it. The house must be lived.” The surroundings are deferential, completed by a group of friends enjoying conversation encouraged by physical comfort and a visual calm. People are the center of attention, not vases on a low table.

For many decorators, design often starts with a spectacular piece—an Oriental carpet that grounds a room or a carved mantel with a trophy painting above it. “I have not acquired any antiques or paintings,” Armani says. “I think that in this kind of house, antiques should be used sparingly. I wanted a place where you could walk barefoot in the summer and sit by a roaring fire in the winter.”

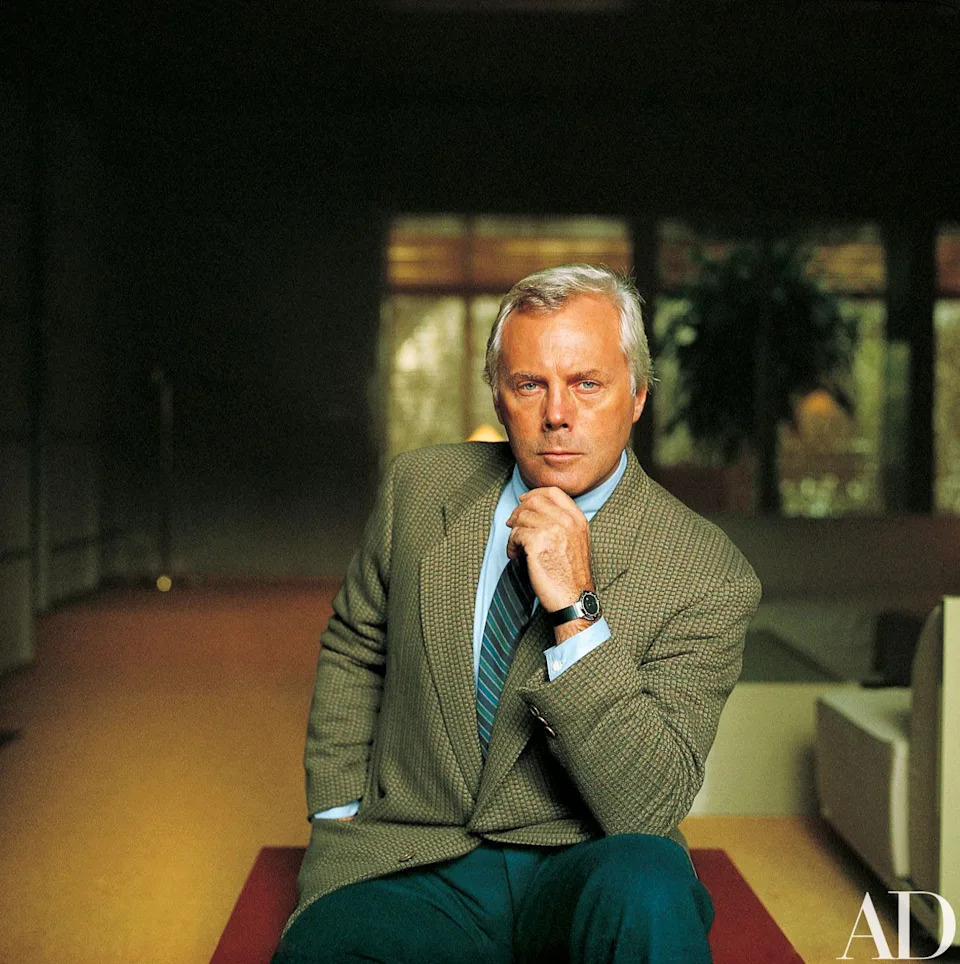

More than 20 years ago, Giorgio Armani thoroughly renovated the interiors but chose not to alter the rustic exterior.

COPYRIGHT ©2003 THE CONDÉ NAST PUBLICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Instead of arranging a hierarchy of pieces, from an imposing armoire or dining table to such accessories as lamps and accent pillows, he conceives of spaces as fields of furniture with an almost evenly dispersed emphasis. The furniture in a portion of the living room occupies an alcove but does not dictate the geometry of the living area. The calm of the rooms comes from the stability of the pieces. Armani chose furniture with big volumes whose weight alone grounds the spaces, each mass almost a complete environment in itself. He may have domesticated the architecture with plain wood and aluminum paneling, but he sized the furniture at an almost architectural scale, and the architecture and furniture marry as near equals.

Armani affirmed the notion of a continuous field from the furniture to the architectural shell with a palette of colors and materials that minimized contrasts while maintaining a discreet differentiation. He upholstered the furniture in natural hues and in materials whose uniformity ties the rooms together and visually expands the spaces. The cocoa floor matting blends with the slightly darker fabric, which, in turn, complements the white paneling on the walls and ceilings. In deference to the walls, whose clean surfaces and soft tones suffuse the interiors with a gentle quiet, he avoided hanging pictures. He also virtually eliminated distracting light fixtures and other accessories. The few lamps he did use qualify as furniture: Two pairs of table lamps, brass cubes for the bases supporting pyramidal shades, echo the simple euclidean geometries of the furniture.

This is a house in which the seamless agreement of the parts builds into a harmony of the whole. The magic lies in the atmosphere that Armani created by balancing the architecture and furniture in a well-tempered environment. Lit to glowing, the spaces ease occupants into a tranquil state of mind. “I believe that fashion and design go hand in hand,” he says. “If you dress in a certain way, you can’t live in a house with a contrasting atmosphere. Harmony is the key to serenity.”

Woven-coconut floor matting offsets a 1930s table and chairs. Interior shutters original to the six-bedroom house remained after the redesign.

COPYRIGHT ©2003 THE CONDÉ NAST PUBLICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The living room narrows at one end to an intimate fireside sitting area. White panels on the walls and ceiling lend the room a nautical air. The house, is “ideal for a simple, ultrarelaxing holiday shared with friends,” says Armani. “I don’t pretend to create industrial design, but I do try to design objects in the cleanest, most clearly defined way,” Armani once said.

A brass canopy bed and a leather club chair are in the serene second master bedroom. Armani designed the pyramidal shades on the 1920 brass-and-wood table lamps. “Lamps are necessary,” he has noted.

COPYRIGHT ©2003 THE CONDÉ NAST PUBLICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

“They’re among the few things that create an atmosphere.” Forming an alcove in the master bedroom are a stair and a small landing that lead to an attic intended for office use. “I chose warm colors—from the khaki on the sofas to the gray of my bed—that would blend with the wood and the matting,” Armani once commented.

COPYRIGHT ©2003 THE CONDÉ NAST PUBLICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

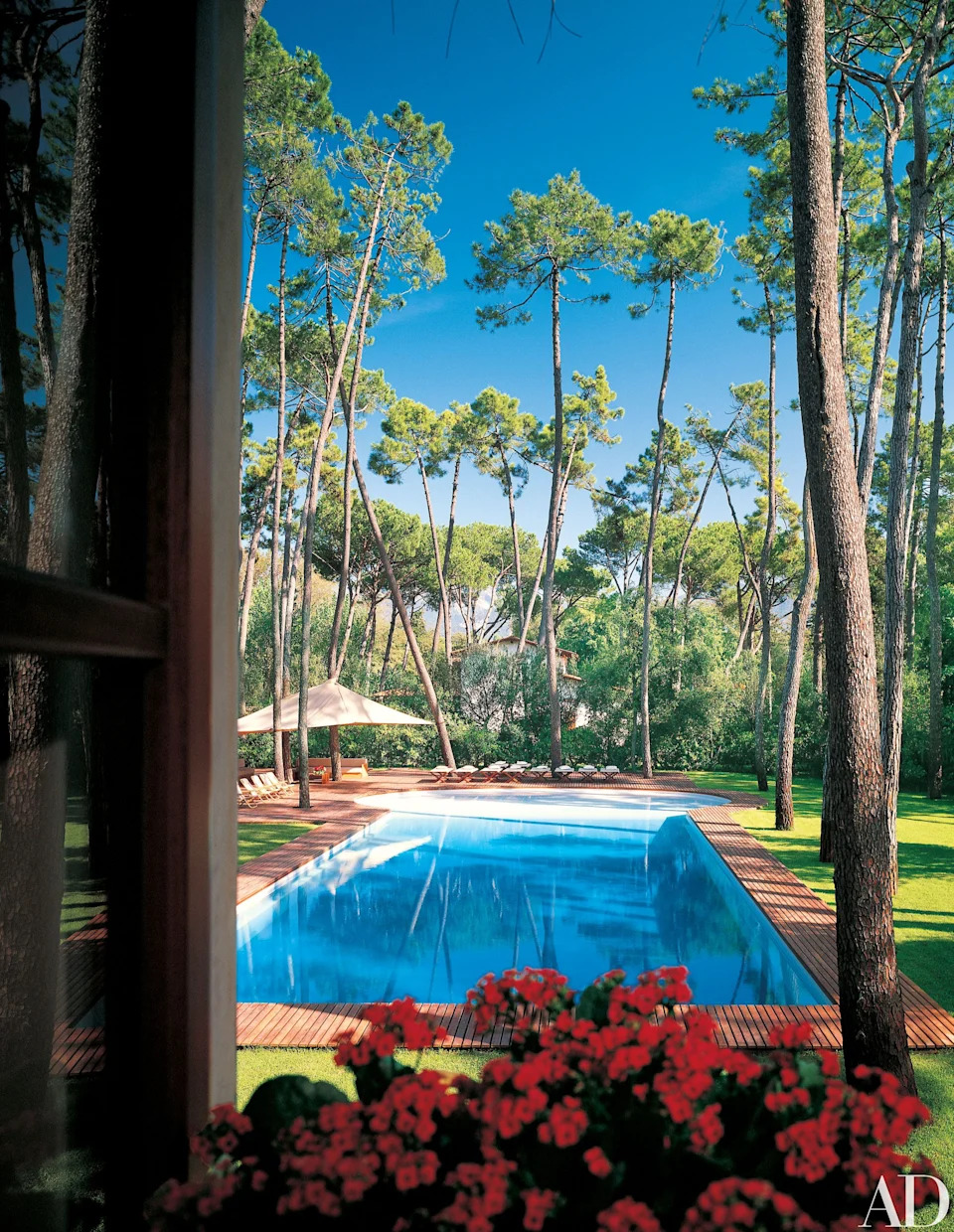

Maritime pines surround the keyhole-shaped swimming pool at the rear of the house. Wood decking mimics the house’s interior paneling. “The pool is perhaps the only thing that is luxurious, but I was so excited to have a pool at the time that I went a little overboard,” the designer says.

COPYRIGHT ©2003 THE CONDÉ NAST PUBLICATIONS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest

More Great Celebrity Style Stories From AD