Despite extensive research on depression, there is still a lack of effective public health strategies to foster positive attitudes toward it. Recent studies highlight a global deficiency in understanding diverse physician perspectives on depression [18,19,20,21]. Our analysis of 2,409 health professionals from five Latin American countries identified four main attitude profiles toward depression.

Skeptical Healthcare Workers doubt the legitimacy of depression as a medical condition, often reflecting stigmatized views previously documented in global studies [22, 23]. In Japan, non-psychiatric doctors’ reluctance to treat depression underscores widespread skepticism about its manageability [24]. Such skepticism is more prevalent among rural and less-educated healthcare workers.

Cautious Healthcare Workers exhibit mixed beliefs, recognizing depression’s seriousness yet doubting the effectiveness of psychological therapies. This caution is distinct from the skepticism observed in some healthcare professionals who more strongly doubt the efficacy of these treatments. Distinguishing between ‘skeptical’ and ‘cautious’ attitudes is important for tailoring educational interventions. While skeptics may require robust evidence to overcome their doubts, cautious individuals might benefit from reassurance and confidence-building measures. Addressing these differences can enhance the effectiveness of education by directly targeting the specific concerns and needs of each group. This skepticism is echoed in studies suggesting that the broader medical and non-medical communities are skeptical about the efficacy of pharmacological treatments [16, 25].

Neutral Healthcare Workers balance acceptance and skepticism about depression. They recognize its importance but are uncertain about treatment effectiveness, reflecting a need for better training in mental health 10,25. These attitudes align with a broader discomfort in dealing with mental illnesses compared to physical ones, especially in regions like Chile, Argentina, and Venezuela [8].

Advocate Healthcare Workers fully recognize depression as a medical condition, emphasizing the necessity of proper diagnosis and management. Their views are supported by international studies, showing varied but generally positive attitudes towards managing depression effectively [26, 27].

The emerging classes reflects an interpretative synthesis of the distinctive characteristics observed in each group after the data analysis, and, although previous studies have used categories focused on specific dimensions, such as, “professional confidence, therapeutic optimism, or a generalist perspective” on depression [28], our approach is intuitively determined by the overall attitudes and practical positioning observed in participants of our study.

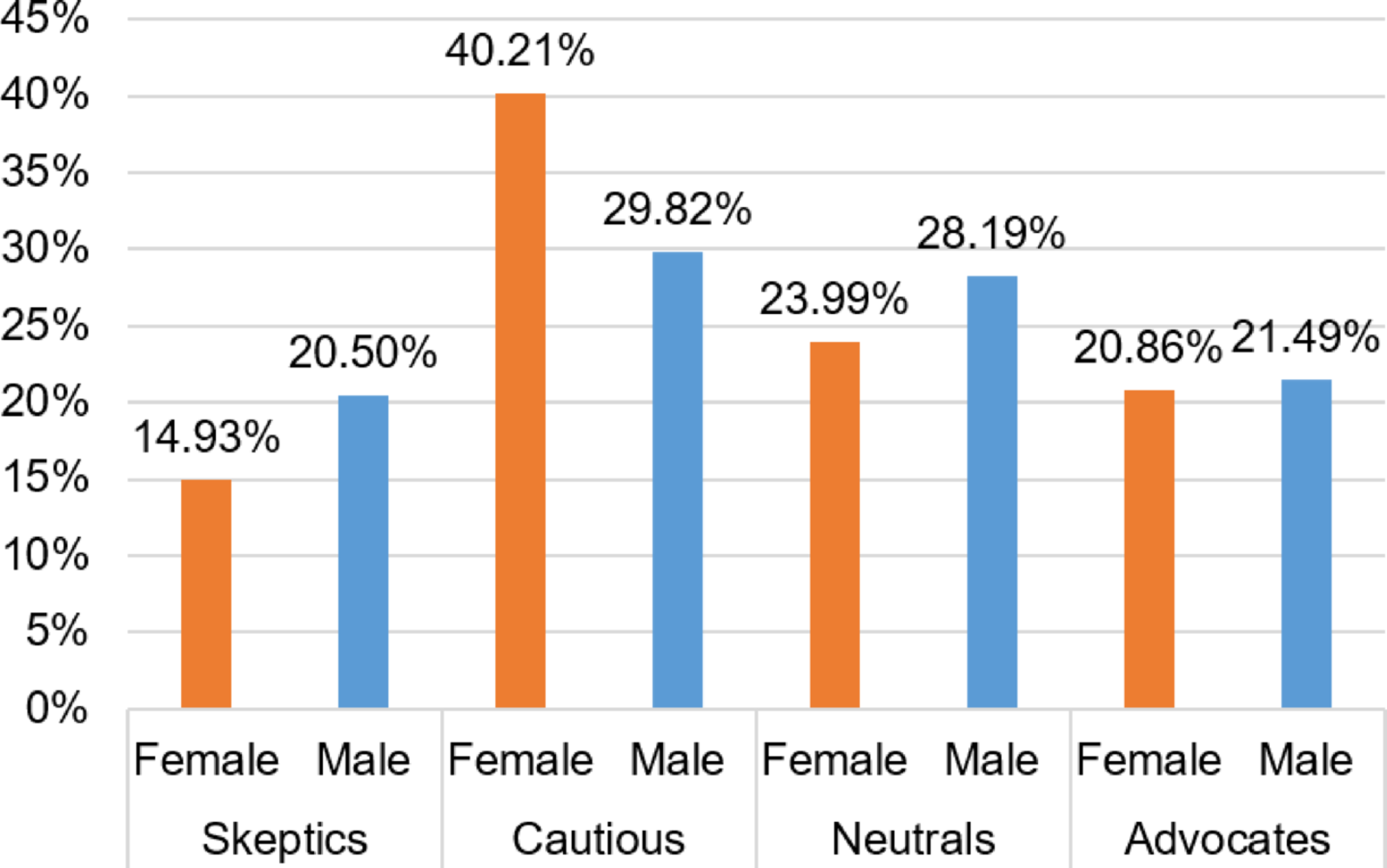

Multinomial logistic regression shows that gender and specialty significantly impact healthcare workers’ attitudes towards depression. Female providers and mental health specialists are more likely to be advocates for recognizing depression as a medical condition, suggesting that specialized training enhances empathy and knowledge. In contrast, male providers and those in non-mental health specialties often display skepticism or caution, reflecting a need for broader mental health education in all medical training. Our findings also reveal that healthcare professionals in Latin America exhibit varied attitudes towards depression, significantly impacting clinical practice. Similar to previous research [29], primary care physicians in our study often display stigmatizing attitudes, preferring to refer patients to specialists rather than manage mental health issues themselves. This reluctance, especially among male healthcare workers and those in non-mental health specialties, underscores the need for broader mental health education [29].

We considered the possibility that differences in class membership across countries could be driven by the proportion of mental health professionals in each national sample. To discard any sample compositional bias, we ran additional bivariate analysis examining the relationship between country and class distribution alongside the proportion of mental health specialists. Although there are notable differences in class membership across countries, our analysis suggests that these are not explained by the distribution of mental health professionals. Countries with similar proportions of mental health specialists exhibit distinct class patterns—for instance, Argentina and Ecuador both have relatively low shares of mental health professionals but differ significantly in the prevalence of Skeptics and Neutrals. Similarly, Peru and Venezuela have comparable mental health representation but differ in their proportions of Cautious and Advocate respondents. These findings indicate that factors beyond professional specialty—such as national context, institutional norms, or training quality—likely play a more central role in shaping attitudes toward depression.

Although our survey did not collect participants’ age or years of practice, generational differences likely influence attitudes toward depression. A systematic review of primary care providers found that older, more experienced doctors often hold more stigmatizing views of mental illness compared to their younger colleagues [30]. This gap likely reflects differences in training and socialization, as many physicians – especially those from earlier cohorts – report needing better preparation to handle mental health issues [30]. In the absence of direct age data, we would expect that younger, recently trained practitioners might be disproportionately represented in the “Depression Advocates” class, while older, long-tenured providers may be more prone to “Skeptical” or “Cautious” attitudes.

Again, our Latent Class Analysis identified four distinct profiles: “Depression Skeptics,” “Depression Cautious,” “Depression Neutrals,” and “Depression Advocates,” mirroring findings that lower mental health literacy and inadequate training lead to poorer outcomes [30]. “Skeptical Healthcare Workers” showed the lowest agreement with recognizing depression, consistent with reports of stigmatizing views linked to less training [30]. Conversely, “Advocate Healthcare Workers” displayed high agreement with depression management, highlighting the positive impact of specialized training. Geographical and socioeconomic factors also influence these attitudes, with rural workers exhibiting more skepticism due to limited resources and cultural stigmas.

The identified subgroups and their correlates represent a crucial starting point for guiding targeted interventions to effectively address stigma-related barriers and improve depression care in Latin America. Generalized interventions might unlikely succeed, so target specific measures should be applied to be able to develop public health strategies that promote educational programs among skeptical and neutral individuals, which can play a pivotal role in reducing barriers arising from differing attitudes toward depression. Notably, several high-income countries have cultivated healthcare provider attitudes akin to our “Depression Advocates” profile through deliberate national strategies. For example, in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, sustained anti-stigma initiatives (e.g. the “Time to Change” campaign in England, Canada’s Opening Minds program, and Australia’s beyondblue) combined with enhanced mental health training have fostered medicalized, non-judgmental views of depression among clinicians [31]. Providers in these settings widely recognize depression as a treatable medical condition (rather than a personal failing) and report high confidence in managing it within primary care [32]. Likewise, countries such as the Netherlands and Australia have implemented collaborative care models and continuing education that embed mental health expertise into primary care teams, further reinforcing clinicians’ comfort in treating depression (by 2015, 88% of Dutch general practices had an on-site mental health nurse supporting depression carebmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com). Adapting these approaches to Latin American contexts is feasible but requires cultural and resource-specific modifications [33]. For instance, anti-stigma campaigns and trainings must be tailored to local beliefs (addressing the notion in some Latin cultures that depression stems from personal weakness) and scaled to available resources – leveraging task-sharing, brief training modules, and community health workers to offset specialist shortagespmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. This integrative paragraph would fit well near the end of the Discussion section, following the description of our latent classes, to contextualize how lessons from high-income countries could inform strategies for shifting Latin American providers toward being “Depression Advocate” stance [31].

To effectively address the different attitudes and structural barriers identified in our analysis, we propose a series of targeted educational and training interventions. First, mandatory mental health training modules should be implemented for all healthcare professionals, with particular focus on non-mental health specialists, to strengthen their capacity to recognize and manage depression. This would directly address the widespread lack of knowledge and confidence observed among skeptical and cautious providers. In addition, incorporating cultural competency training is essential to confront local stigmas and traditional gender roles that influence mental health attitudes, especially in rural areas where such norms are often more deeply rooted. Integrating collaborative care models—where mental health specialists support primary care physicians—can further aid cautious providers by improving their ability and confidence to manage depression in routine practice. Establishing peer support networks would also enable healthcare workers to share challenges and best practices, fostering collegial reinforcement for more empathetic and informed care. Moreover, ongoing professional development initiatives focused on up-to-date mental health treatments can help those in the neutral and cautious profiles gradually shift toward an advocate-like stance. Finally, the implementation of routine assessments to track providers’ attitudes over time would support the adaptive refinement of educational strategies and contribute to overall improvements in the quality of mental health care.

Study limitations

The nature of the study may have influenced the development of the latent class analysis, generating several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents us from inferring how attitudes may change over time, which could lead individuals to shift between latent classes. The online distribution of the survey could have introduced selection bias, potentially overrepresenting certain groups. Additionally, temporal differences in data collection across the two study periods may have affected outcomes, although we applied statistical controls to assess the consistency of class distributions. As with most survey-based research, the use of self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall and social desirability biases. The uneven distribution of medical specialties and gender in the sample may also limit the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, latent class analysis depends on model assumptions and results may vary with different specifications determined by the researcher. Finally, a technical error during data collection prevented the consistent recording of participants’ age, limiting our ability to assess generational effects. Nonetheless, we expect that age may influence attitudes through differences in mental health literacy, exposure to training, and evolving cultural norms around the medicalization of psychological distress, which could shape how depression is perceived and managed in clinical practice.

Further research

While this study offers a novel classification of healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward depression in Latin America, it also opens important avenues for future research. First, incorporating age and years of professional experience in future surveys would allow for a more precise analysis of how generational factors shape attitudes—a limitation noted in our current dataset. Second, qualitative studies could deepen understanding of the contextual reasons behind class membership, especially in countries with contrasting patterns. Finally, intervention studies are needed to evaluate whether targeted training programs, anti-stigma campaigns, or collaborative care models can effectively shift providers from skeptical or neutral profiles toward a more advocate-oriented stance. Longitudinal designs would be particularly valuable to assess whether attitudinal changes among healthcare workers translate into improved depression care and patient outcomes.