It begins like any ordinary world. Rebellious teens steal from their parents while they’re asleep. Groups of men huddle to harass women. India preps its defences against unfriendly neighbours. Journalists chase stories with relentless hunger. The world feels almost like ours…except in its details. The teenager doesn’t steal money from his parents’ wallet; instead, he takes something far more precious: their time. The men ogle women wearing traditional odhnis and carrying babies on their hips – tiny, colourful, tentacled babies. India’s neighbour is not a rival nation but something big, red, and extraterrestrial: Mars. And the journalists? They find themselves covering Yetis…and Gods.

A funhouse mirror

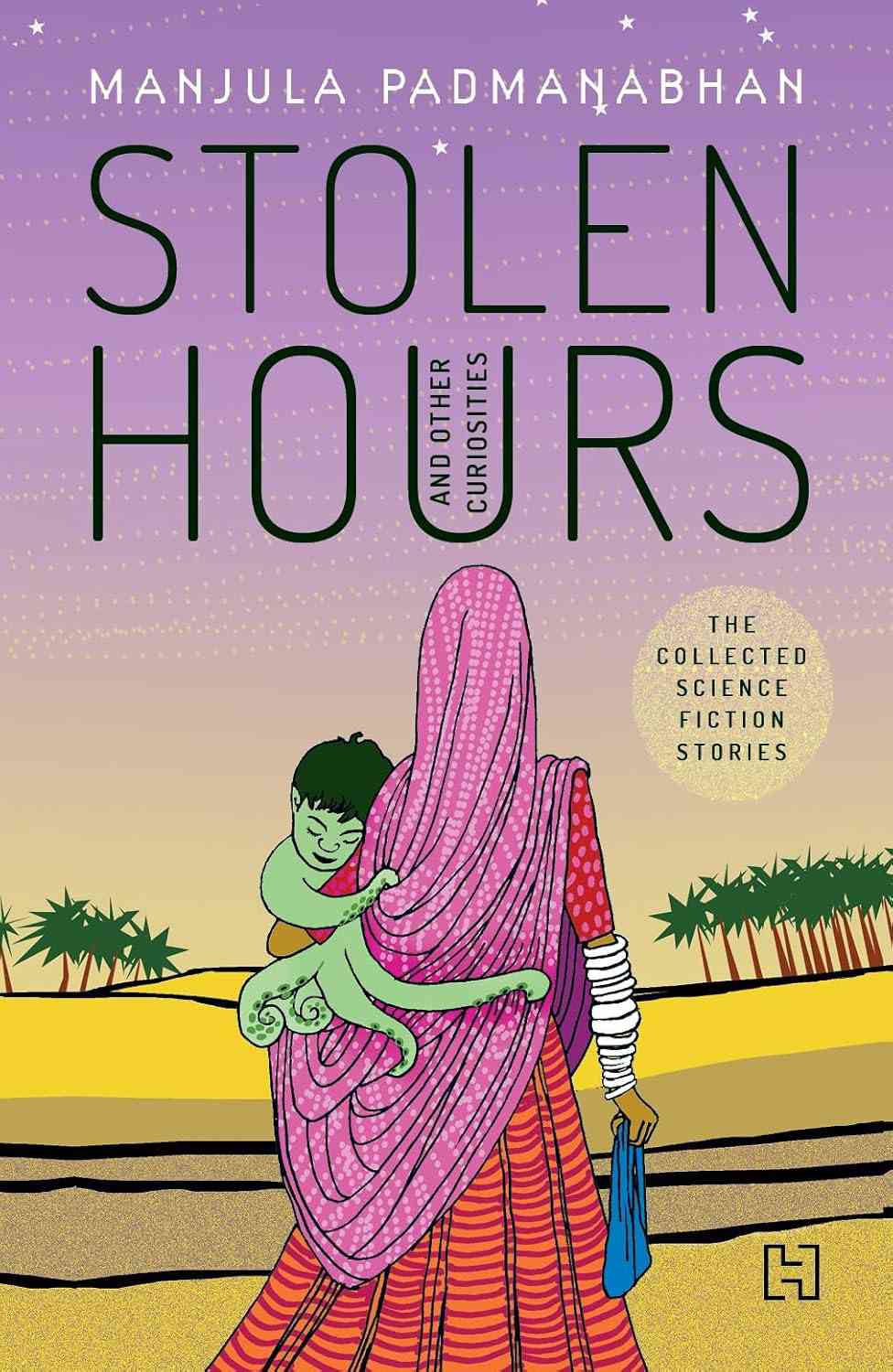

In Stolen Hours and Other Curiosities, author Manjula Padmanabhan takes what is familiar and tilts it, just slightly, and then spectacularly. Most of the stories have previously appeared individually in magazines and anthologies, with a few new ones completing the collection. Through a handful of surreal details, she transforms everyday experiences into strange, glittering visions. Her sharp-witted stories mirror the ethos of India, of the world, and of human beings at large. Except this reflection is through a funhouse mirror, one that distorts to reveal.

This is, arguably, science fiction’s greatest strength: to reassess the ordinary through the language of the extraordinary. We find stories so essential because they help us narrativise and understand our own natures. They do this whether they reveal complex truths about the human conscience, illuminate realities of marginalised lives, or even tell a deceptively simple love story. However, sci-fi, as a genre, stretches these explorations to stellar and even extraterrestrial dimensions.

In his book Science Fiction, academic and novelist Adam Roberts identifies this genre’s core feature as a “point of difference”, a singular deviation that separates the fictional world from our own. Whether it’s time machines, faster-than-light travel, dystopias, or ruined Earths, the genre’s imaginative departures create distance from our reality. Yet, paradoxically, that distance allows sci-fi to look back at our world with sharper focus. The most effective sci-fi stories balance novelty with familiarity. They create universes that feel spectacular enough to engage and entertain but are still grounded in recognisable human experience. This careful blend helps produce the right distance required to examine reality more clearly. For instance, an exaggerated world like the one in Sultana’s Dream, where women rule and men are confined, makes it easier to reflect on our own world, where the gender roles are reversed. However, writing sci-fi comes with a caveat: go too far, and the reader loses interest.

Padmanabhan deftly manages this balance between estrangement and familiarity, between imaginative possibilities and scathingly exposed reality. In the author’s note to Stolen Hours, she writes that growing up in many countries made her a “naturalised outsider.” Science fiction, she explains, becomes a means of “celebrating the othering.” It grants her the freedom to stretch and warp human realities, to examine them through distortion, and to make visible what everyday realism often cannot. Stolen Hours offers a ride through altered worlds that remain, at their core, an examination of our own.

Manufacturing alternate realities

The collection opens in a place of old-world charm, where people wear tunics, mirrored turbans, and embroidered slippers, and fragile old merchants offer curious wares. In this first story, a young boy, sheltered by his family of mothers and sisters, slips away to meet a merchant in secret. The merchant trades in something forbidden, something the boy has never felt. In “The Pain Merchant”, Padmanabhan conjures a world where pain has been banished. And so, a boy who has never felt it seeks out an old merchant who sells pain “like perfume.” The tale lasts only a few pages, yet it grapples with many ideas. If you could delete pain from the human repository of experience, should you? How essential is pain? The story suggests it is so essential that, when removed, people are not met with relief. Instead, pain becomes a contraband commodity. It also toys with what pleasure, the “Siamese twin” of pain, might feel like in its absence. Interestingly, there are no pleasure merchants here, only pain merchants and young boys who chase after them.

For true sci-fi fans, the book offers familiar premises. “Interface” imagines a world where life and technology are split into “organics” and “inorganics.” Scientific progress has gone so far that machines feel almost alive, even warm to the touch. Humanity’s worst fears about AI and robots come true when the tech collectively decides to revolt against their enslavement. However, Padmanabhan is subversive even in this familiar plot. The tech uprising isn’t bloody or violent…it is calm, organised and much worse. Meanwhile, in “Freak”, it is finally confirmed that Yetis do exist. A talented hunter, aptly named Hunter, goes to great lengths to track and capture the beast. But this creature is imagined with dimensions more intricate than ordinary humans can perceive, and the story leaves you wondering whether it is about Yetis at all.

These short stories also hold dystopian futures for us to reckon with. In India “2099”, a man from 1999 wakes up a century later after spending a hundred years in a transit chamber. He finds a sleek, efficient world: the air smells of mangoes, monuments like the India Gate and Qutub Minar stand proud, and the horizon is green and smog-free. Yet all is not as it seems. While he slept, half of India was wiped out by nuclear war, and the survivors rebuilt what was lost – or at least, the illusion of it. The story plays on a familiar impulse to imagine an advanced, harmonious future, only to reveal that beneath a polished facade, human nature remains unchanged. A similar theme is echoed in “Adaptation”, where human bodies are engineered for a post-apocalyptic Earth. Yet despite chlorophyll-infused skin and perfect proportions, the humanity underneath betrays them in familiar old ways.

“A Better Tomorrow” is both utopian and dystopian, depending on where you stand. After humanity overruns the planet like an unchecked disease, a heroic virus saves the day. Humans are not wiped out, only limited and confined. Everyone is happier for it.

Then there are stories that take familiar concepts and carry them to unexpected ends. In “Feast”, a European vampire journeys to India, unsettling a myth we often accept without question by casting it onto foreign soil. How does the Indian legal system reckon with the quiet disappearance of a few among its billion-strong population? Do they even notice? And what happens when a vampire is forced to navigate a culture that holds no clear heaven or hell, no neat divide between good and evil? A place where death itself carries other meanings, older and stranger than he can fathom?

Ultimately, like all good stories, Stolen Hours and Other Curiosities entertains, unsettles, and leaves you pondering long after you’ve put it down. Manjula Padmanabhan strikes this balance with care, often choosing to show rather than tell. In “The Pain Merchant”, the little boy has only mothers and sisters…no fathers or brothers in a world without pain. Nowhere does the story draw attention to this. But if you read closely, every tale leaves you, as the title suggests, curious and wondering.

Stolen Hours and Other Curiosities, Manjula Padmanabhan, Hachette India.