When the ‘Razor’ Robertson era began with a two-Test series against England in July 2024, one of the men sitting on his shoulder in an advisory capacity was Sir Wayne Smith. ‘The Professor’ enjoyed the nominal title of performance coach and he returned to camp ahead of the first game in the double-header against the Springboks at Eden Park a few weeks ago.

As I wrote back then, this seemed a clear sign Robertson would move the men in black back to the future, and reinstate Smithy’s world-conquering counterattack which had dominated planet rugby for the better part of a decade.

How wrong I was. Despite his frequent visits to All Black HQ, the influence Smith’s philosophy has had on this coaching group is to put it politely, negligible. There is little evidence of Smithy’s counterattack policy and the All Blacks no longer run away from opponents in the fourth quarter under its power. New Zealand was minus 17 in the points for/points against ledger in the final 20 minutes at the Rugby Championship – well behind South Africa and Australia.

Sir Wayne Smith is widely regarded as one of the greatest coaching minds in rugby history (Photo by Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

Sir Wayne Smith is widely regarded as one of the greatest coaching minds in rugby history (Photo by Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

In the salad days of the Henry-Hansen-Smith trifecta, the Professor borrowed heavily from the National Basketball Association; the Los Angeles Lakers ‘fast-break’ offence of the 1980s, recast by Gregg Popovich’s San Antonio Spurs three decades later. The idea of ‘showtime’ was to create a turnover with strong defence, then use transition sprints to spread the court and create two-on-ones and three-on-twos on the counter, with strong drives to the basket to pull in defenders and create space for others. Super-slick passing and the swift identification of mismatches were key to success.

In the great All Blacks teams of the 2010s, Smithy wanted 14 men on their feet in defence, generating lightning-quick turnovers with the ball passed through second receiver automatically, and everyone working at maximum capacity for the first three phases of the transition from defence to attack. As he observed during an excellent Rugby Site mentoring session:

“When I was young and playing the game at youth level, I was taught you always base your attack on what the defence is doing. Your kick counterattack should be based on what the opposition chase is doing.

“I want to try and grow the understanding of how to counterattack off kick receipts, what to look for, and how best to exploit a chasing line. You get stable as soon as you can as an attacking team, and attack them while they are still unstable, or unstructured as a defence.

“It’s the best chance of success. There is a great attacking platform [to be had] off turnover and kick receipts. Counterattacks dominate the scoring in the modern game, and it’s a part of the game that needs to be coached.”

The Professor’s aims were the same as the Lakers’, who won five championships in that golden decade of the 1980s, and the Spurs with their four NBA titles achieved between 2003 and 2014. In Smithy’s heyday the All Blacks would score around half of their tries via counterattack off either kick receipts or turnover ball. Look at the performance of Razor’s All Blacks at the current Rugby Championship, and the stats tell a very different story.

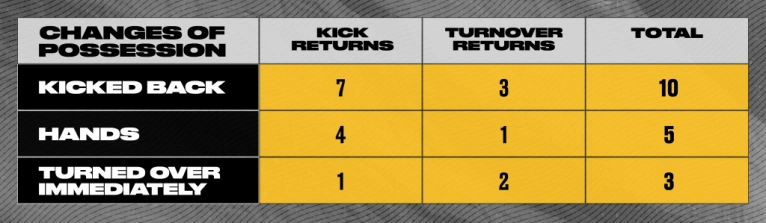

Wind the clock back 10 years, and you would expect this table to be the other way around. Now it is the Springbok who are confidently expecting to exploit unstructured countering situations, and the All Blacks have sunk to the very bottom of the pond, with only two tries deriving from turnover scenarios.

The first Bledisloe Cup game against Joe Schmidt’s Wallabies gave an indication why that is the case. The following general table shows what the All Blacks were doing with their turnover ball at Eden Park.

Of a total of 18 countering opportunities in the game, the All Blacks kicked back 10 [56%], turned over three immediately [17%], and only ran back five [27%]. All five returns direct from kick-off were either kicked back to Australia immediately, or after one short forward phase. There was no attempt made to run back out of their own 22.Of the five returned through the hands, two attacks switched back to the short-side within the first three phases, while the other three utilised the full width of the pitch. Of the three which used the full width, all had positive outcomes, with one penalty won, one clean break, and a try.New Zealand did not return a kick using the full width of the field until the 53rd minute, and it resulted in a break by Jordie Barrett. They scored their only kick return try of the tournament so far in the 75th minute to clinch the match.

When New Zealand assistant Scott Hansen talked recently about what improvement would look like on the forthcoming end-of-year tour, it did not sound as if explosive counter-offensives from deep were on the menu.

“It’s [about] growing our set piece, the quality possession that we provide… It’s applying pressure in the right area of the field.

“We’ve had a good review of the most recent competition around where we can get some learnings, and fundamentally for us, that is about controlling possession.”

The risk-averse policy off turnover ball was amply illustrated by two sequences occurring in the first half.

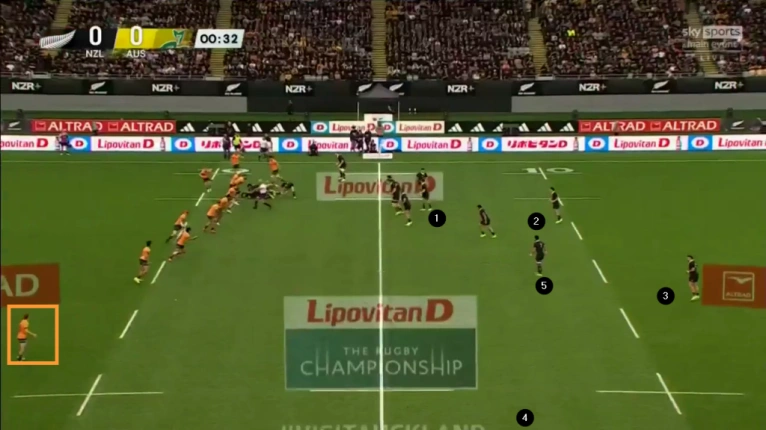

After a magnificent defensive catch by Jordie Barrett, the Walalby defence is offering space out wide, with the last edge defender [14 Harry Potter] standing inside the far 15m line. There are four New Zealand backs available to the wide side of the field and left wing Caleb Clarke is standing beyond Potter on the touch-line. The ace up the Kiwi sleeve is the presence of Ardie Savea [‘5’] as the widest forward, and we know how lethal Ardie can be in space or in one-on-one contests.

The Wallabies are giving New Zealand width but the All Blacks are refusing to accept the free gift.

Clarke is ignored completely, and instead of using Ardie as a runner the All Blacks use him rather tamely, to clean out over another forward run in the middle of the field. There is hardly any sense sense of ‘fast-break’ urgency as he ball is shifted back to the short-side and Wallace Sititi is hustled into touch.

The same pattern was repeated just after the half-hour mark.

Another catch by Jordie, another automatic forward run and switchback to the short-side on second phase. Within two more phases of play, the ‘counterattack’ had decelerated to the point where there was no option but to kick the ball back to Australia via the boot of replacement Damian McKenzie.

A turnover return in the eigth minute had showed the way, but it was not until the 53rd minute the men in black picked up the hint and ran with it.

Here is the Professor’s theory of mismatches in action, with a line of Kiwi backs facing a defensive group featuring two forwards, Harry Wilson and Lukhan Salakaia-Loto, running inside the last defender Max Jorgensen. The real mystery was why it took the All Blacks another 46 minutes of game time to locate the same space. When they finally did, it looked very much as if Jordie Barrett had had enough of the gameplanning straitjacket.

It was almost the first time in the game that there was a definite uplift in the All Blacks’ intensity and speed in a situation with a change of possession, as the ex-Leinsterman glides past Fraser McReight on the mismatch.

Twenty minutes later, the All Blacks worked hard to realign as a countering team for the first time in the game and reaped an immediate reward on the kick return.

Replacement second five-eighth Quinn Tupaea doubles back in double-quick time to make the extra man in midfield, lightning-quick ball links the pod of forwards and the backline instantly, and between them Billy Proctor and Tupaea are able to exploit the defensive uncertainty of Joseph-Aukuso Suaalii at centre. A current Chiefs man sets up a try of which a great ex-Chiefs coach would have been proud, but It was the first time New Zealand had scored a kick return try in over 400 minutes of footy.

If Smith is casting an close eye over the current All Blacks, in his more reflective moments he is probably wondering what has become of the counterattacking strategy he devised. The sense of urgency, of a countering team working at maximum speed and pressure in short, overhwelming spurts of activity is almost entirely absent. A couple of one-out forward rumbles followed by either a switch back to the short-side, or a tit-for-tat kick to the opponent are far more likely. ‘Showtime’ it is emphatically not.

Back in 1982, the LA Lakers finally abandoned a Paul Westhead-coached, half-court offence which Magic Johnson had derided as ‘slow’ and ‘predictable’. Johnson folded his arms and went on the sporting equivalent of a hunger strike, and Lakers owner Jerry Buss backed him to the hilt: “There was a lack of excitement on offense that I missed. I enjoyed Showtime and I wanted to see it again.I’m speaking as much as a fan as anything else.”

New Zealand rugby supporters may be thinking many of the same thoughts 43 years later. Without that full-court dynamism and the sense of pure theatre involved in a counter from deep, who exactly are Razor Robertson’s All Blacks?