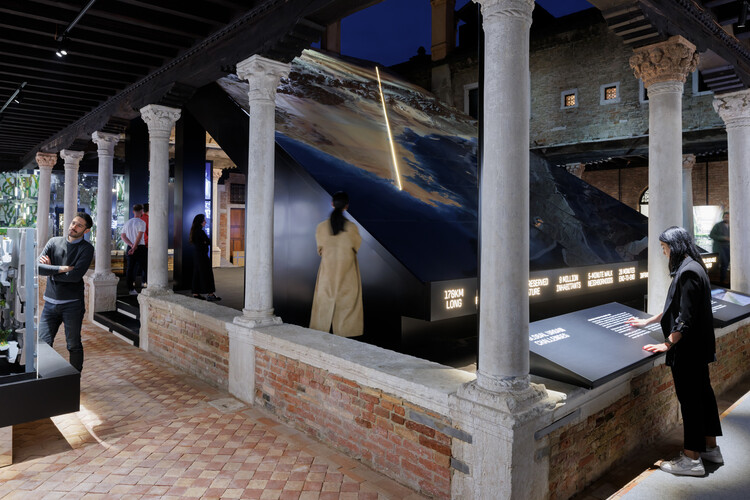

‘Zero Gravity Urbanism – Principles for a New Livability’ at the Abbazia di San Gregorio, Venice. Image © Iwan Baan

‘Zero Gravity Urbanism – Principles for a New Livability’ at the Abbazia di San Gregorio, Venice. Image © Iwan Baan

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1035190/staging-culture-the-architect-as-curator

Architecture has never been confined to the act of building. It constantly negotiates between material practice and intellectual reflection, yet throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, many architects felt that the built project alone was insufficient to address the full range of questions facing the discipline. Economic pressures, political contexts, and programmatic demands often narrowed the scope of practice.

Exhibitions and curatorial platforms, by contrast, created spaces of experimentation and critique, opening arenas where architecture could interrogate itself, where its past could be reinterpreted, its present challenged, and its future projected. In this tension, the figure of the architect-curator emerged, treating curating itself as a form of design — not of walls or facades, but of discourse, narratives, and frameworks of meaning.

The importance of this role is difficult to overstate. Without curatorial interventions, architecture risks being reduced to service or style, stripped of its capacity for critical thought. Biennales and triennales in particular have become fundamental stages where the discipline reflects on its identity, formulates new agendas, and tests its limits. To see the architect as curator is therefore to recognize the necessity of a figure who not only constructs buildings but also builds intellectual and cultural infrastructures — ensuring that architecture remains a practice of ideas as much as of forms.

Related Article Expanding Practice: Architecture Think Tanks at the Intersection of Research and Design Canonizing the Modern

When Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock organized Modern Architecture: International Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932, they did more than assemble a collection of contemporary buildings; they invented a narrative. Modernism had already emerged in Europe through figures such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe, yet it lacked coherence as a cultural movement. In the United States, isolated examples existed — Richard Neutra in California, Howe & Lescaze in Philadelphia — but they were seen as exceptions rather than part of a broader shift. MoMA’s exhibition changed this perception.

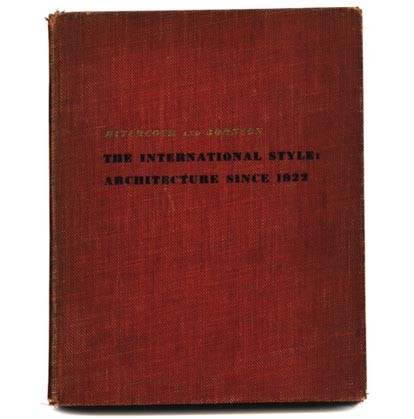

By bringing these works together under the newly coined label of the International Style, Johnson and Hitchcock presented modernism as a unified language rather than a series of disconnected practices. The accompanying book, The International Style: Architecture Since 1922, distilled the movement into three principles: volume over mass, regularity over symmetry, and the avoidance of ornament. These criteria, deliberately abstract, served as curatorial tools as much as theoretical definitions. This framing, however, came at a cost. By privileging rationalist and purist examples, the exhibition downplayed the richness of modernism’s early diversity, neglecting expressionist architecture in Germany, regional experiments in Scandinavia, or the socially driven modernism of Eastern Europe. The curatorial lens flattened a heterogeneous landscape into a single, coherent style. Yet this simplification proved powerful through the authority of the museum; an avant-garde tendency was transformed into cultural orthodoxy.

The consequences were immediate and far-reaching. For American architects, the exhibition provided a canon that informed both education and practice. In the decades that followed, the International Style spread through universities, corporate architecture, and civic institutions, embedding itself in the built environment of postwar America. More broadly, the exhibition institutionalized the idea that architecture could be curated like art, with selections and narratives shaping how the discipline was understood by professionals and the public alike.

Johnson’s exhibition also marked a turning point when compared to earlier precedents. The 1927 Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, organized by the Deutscher Werkbund under Mies van der Rohe, had already gathered leading architects to experiment with modern housing, while the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris revealed the tensions between ornament and emerging functionalism. Both events showcased work; MoMA’s exhibition, by contrast, codified it.

As historians such as Joan Ockman and Mary McLeod have emphasized, the 1932 exhibition was not simply descriptive but prescriptive. It taught audiences how to see architecture, foregrounding form and abstraction while muting the politics, technologies, and social agendas that had also shaped modernism in Europe. In doing so, Johnson and Hitchcock celebrated the movement even as they reduced its complexity, transforming it into a predominantly aesthetic project. The MoMA exhibition stands, therefore, as one of the earliest and most influential examples of the architect as curator: Johnson and Hitchcock authored a discourse, inventing a style that would dominate architectural culture for decades.

Memory and Typology

If the MoMA exhibition of 1932 canonized modern architecture through abstraction, Aldo Rossi’s intervention at the 1973 Triennale di Milano redirected the discipline toward memory, continuity, and typology. By the early 1970s, Modernism was in crisis: the optimism of the postwar decades had waned, the promises of functionalism were increasingly questioned, and younger generations were turning to history and urban form in search of renewed meaning. Italy, in particular, became a laboratory for this critique, where the failures of modernist housing projects and the political turbulence of 1968 created fertile ground for theoretical and cultural debate.

The Museum of Modern Art 53rd Street entrance. Image © Timothy Hursley

The Museum of Modern Art 53rd Street entrance. Image © Timothy Hursley

But the Triennale was, by nature, a contested platform. Since its inception in 1923, it had oscillated between avant-garde experimentation and institutional display. Under Rossi’s influence in 1973, however, it became a stage for intellectual reflection on the discipline’s foundations. Alongside collaborators of the Tendenza, such as Carlo Aymonino and Giorgio Grassi, Rossi presented drawings, models, and theoretical projects that emphasized the persistence of types. Their approach resisted the narrative of modern architecture as linear progress, proposing instead a cyclical conception of history in which architecture was bound to collective memory — something that Rossi had already articulated in L’architettura della città, where he argued that the city is not merely an accumulation of functions but a collective artifact shaped by memory, inseparable from typology.

La Classica, 1976. Image © Gianluca Di Ioia

La Classica, 1976. Image © Gianluca Di Ioia

This curatorial stance was not nostalgic. By reasserting the relevance of typology, Rossi challenged the reduction of architecture to mere function or technology, insisting that meaning resided in formal permanence. In this sense, the exhibition became a laboratory of theory, where spatial arrangements were treated as arguments and curatorial choices as intellectual propositions. For scholars such as Vittorio Gregotti, Rossi’s curatorial strategy marked a decisive turn: architecture was no longer positioned simply as an instrument of modernization but as a cultural practice embedded in history. The implications were far-reaching. Rossi’s Triennale influenced not only Italian debates but also international discussions on postmodernism. Figures such as Rafael Moneo, Oswald Mathias Ungers, and later Peter Eisenman engaged with his emphasis on typology and memory, often through their own exhibitions and writings. The Triennale thus demonstrated how exhibitions could operate as sites where architecture stages its own debates, advancing alternative ontologies for the discipline.

Staging the Postmodern

By the end of the 1970s, modernism no longer carried the aura of inevitability it once had. Its functionalist doctrines had been challenged, its universal claims exposed as reductive, and architects across Europe and the United States were experimenting with irony, symbolism, and historical reference. Paolo Portoghesi’s La Presenza del Passato, the first officially recognized Venice Architecture Biennale in 1980, crystallized these tendencies into a single event. More than an exhibition, it staged a new intellectual and cultural condition for the discipline: the arrival of postmodernism.

© Andrea Avezzù. Cortesía de La Biennale di Venezia

© Andrea Avezzù. Cortesía de La Biennale di Venezia

The centerpiece of Portoghesi’s Biennale was the Strada Novissima, an installation inside the Corderie dell’Arsenale composed of twenty facades designed by international architects. Each facade was a statement, employing quotation, eclecticism, and historical references that directly opposed the formal austerity of the International Style. But this was more than scenography; it functioned as a manifesto that dramatized Charles Jencks’s claim that “modern architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri, on July 15, 1972, at 3:32 p.m.” (the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project). Where modernism had sought universality, Portoghesi’s curatorial gesture celebrated multiplicity. Where Johnson’s MoMA show had canonized, Portoghesi’s Biennale theatricalized, exposing the discipline’s internal debates and elevating postmodernism to global recognition.

Courtesy of “The Pruitt Igoe Myth”

Courtesy of “The Pruitt Igoe Myth”

The Biennale’s impact was immediate. For some, it was liberating: Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s call for “learning from Las Vegas” found a global stage, legitimizing ornament, humor, and popular culture in architecture. For others, it was a provocation. Critics such as Manfredo Tafuri and Hal Foster attacked the postmodern turn as politically complacent, a retreat into surface and spectacle at a moment of social upheaval. But what made Portoghesi’s curatorship important was its intellectual framing by naming the exhibition The Presence of the Past; he presented postmodernism not just as a style but as a necessary reconciliation between tradition and modernity, between memory and innovation. The Biennale became the space where architecture could acknowledge its historical depth while trying out new cultural forms. And like Johnson’s 1932 MoMA show had institutionalized modernism, Portoghesi’s Biennale institutionalized postmodernism, showing how the architect-curator can not only display architecture but define its intellectual trajectory.

Deconstructing the Discipline

By the early 2010s, the Venice Architecture Biennale had become associated with spectacle. Each edition seemed to compete in displaying the most spectacular projects by the most recognizable names, reinforcing the “starchitecture” system that dominated the profession. Against this backdrop, Rem Koolhaas’s curatorship of the 2014 Biennale marked a radical rupture. Under the title Fundamentals, Koolhaas refused to stage a celebration of contemporary buildings. Instead, he sought to strip architecture back to its essence, dismantling the myths of authorship and novelty to expose the discipline’s basic DNA.

The exhibition was organized around three parts: Absorbing Modernity 1914–2014 invited national pavilions to reflect on a century of homogenization and modernization, highlighting how local identities were transformed, and often erased, by the global spread of modernist paradigms; Monditalia using Italy itself as a lens, blending architecture, politics, cinema, and performance to narrate the contradictions of a country often described as a laboratory of the modern condition; and Elements of Architecture, developed with Harvard GSD, focused on fifteen fundamental components — wall, floor, ceiling, door, window, stair, and so on — each examined through historical, cultural, and technological lenses.

Toilets, at “Elements of Architecture” at the Venice Biennale. Image © Nico Saieh

Toilets, at “Elements of Architecture” at the Venice Biennale. Image © Nico Saieh

This structure revealed that Koolhaas’s curatorial strategy was to deconstruct the discipline by fragmenting it. Instead of asking what architecture “is” today, he asked what it is “made of.” The focus on elements moved attention away from individual architects and iconic buildings, placing the spotlight on the shared grammar of construction that transcends geography and authorship. In the Central Pavilion, visitors encountered displays on the evolution of ceilings, escalators, or toilets — elements usually taken for granted, now reframed as historical artifacts and cultural devices.

Windows, , at “Elements of Architecture” at the Venice Biennale. Image © Nico Saieh

Windows, , at “Elements of Architecture” at the Venice Biennale. Image © Nico Saieh

The intellectual stakes of Fundamentals were high. Koolhaas argued that the twentieth century was not only a story of modernism’s triumph but also of modernity’s erasures: the loss of local building traditions, the standardization of form, and the commodification of space. By dismantling the discipline into parts, he invited architects to confront what had been forgotten, suppressed, or rendered invisible in the pursuit of progress. Fundamentals acted as a historiographic project, curating the hidden continuities of architectural culture.

The reception was polarized. Admirers praised its ambition and its refusal of spectacle, seeing it as a much-needed corrective to the superficiality of the star system. Critics, however, argued that by focusing on elements in isolation, Koolhaas risked reducing architecture to taxonomy, stripping it of context and political urgency. Sylvia Lavin noted that Elements of Architecture bordered on encyclopedic detachment, while others suggested that the project reflected Koolhaas’s own tendency to oscillate between critique and complicity with global capitalism.

Koolhaas preparing the exhibitions.. Image Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Koolhaas preparing the exhibitions.. Image Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Nevertheless, the significance of Fundamentals is undeniable. Koolhaas used curatorship not merely to reflect the state of architecture but to redefine it. By shifting attention from authors to elements, from novelty to continuity, he staged the discipline itself as an object of analysis. The Biennale became less a showcase of projects than a collective anatomy lesson, a moment of self-reflection for a profession caught between global homogenization and cultural specificity. In retrospect, Fundamentals can be read as a counterpoint to the postmodern pluralism of the Strada Novissima. Where Portoghesi staged a street of facades, Koolhaas dismantled the building into components. Both acts reveal the power of curatorship to reset the coordinates of architectural debate, affirming that exhibitions are not passive containers of content but active constructors of discourse.

Decolonizing the Stage

If Johnson canonized, Rossi theorized, Portoghesi theatricalized, and Koolhaas deconstructed, Lesley Lokko’s curatorial project at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale sought to decolonize. Her exhibition, The Laboratory of the Future, marked a decisive departure from traditional narratives by foregrounding African and diasporic voices and placing questions of identity, race, and climate at the center of architectural discourse. In doing so, Lokko expanded the figure of the architect-curator into that of cultural critic and activist, using the stage of the Biennale not only to showcase projects but also to challenge the structures of power that shape the discipline.

Overlapping crises defined the context for Lokko’s Biennale: the accelerating effects of climate change, the persistence of global inequality, and the urgency of rethinking architecture’s complicity in colonial and extractive systems. While previous editions often privileged Euro-American perspectives and established practices, Lokko insisted on a radical rebalancing. More than half of the participants were from Africa or the African diaspora, and the exhibition framed the continent not as a marginal territory but as a site of experimentation, resilience, and cultural production.

Sections such as Force Majeure gave visibility to architects, artists, and activists whose work addressed realities often excluded from mainstream discourse, from informal settlements to climate adaptation and cultural identity. At the same time, the very notion of a “laboratory of the future” redefined the temporality of the Biennale, presenting it as a space of ongoing experimentation rather than definitive conclusions, privileging questions over answers.

The impact of Lokko’s Biennale was twofold. On one hand, it expanded the geography of architectural discourse, creating visibility for practices long excluded from the canon. On the other hand, it reframed the role of the Biennale itself: no longer a showcase of novelty or a staging of styles, but a political platform. Critics praised its ambition and attention to equity, though some questioned whether the Biennale as an institution could fully accommodate such a radical reorientation. Nonetheless, the exhibition succeeded in shifting the coordinates of debate, ensuring that decolonization, identity, and justice are no longer peripheral but central to the architectural agenda.

© Marco Zorzanello, Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

© Marco Zorzanello, Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

By positioning architecture as a tool of cultural and political struggle, Lokko’s curatorship continues the lineage of Johnson, Rossi, Portoghesi, and Koolhaas but pushes it further. Her intervention demonstrated that curatorial acts are not only about canonizing or deconstructing but also about redistributing authority and amplifying marginalized voices.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: The Architecture of Culture Today. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Model of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye from Modern Architecture- International Exhibition [MoMA Exh. #15, February 9-March 23, 1932]. Image via The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photographic Archive

Model of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye from Modern Architecture- International Exhibition [MoMA Exh. #15, February 9-March 23, 1932]. Image via The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photographic Archive Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Jr. and Philip Johnson- THE INTERNATIONAL STYLE- ARCHITECTURE SINCE 1922. Image via www.modernism101.com

Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Jr. and Philip Johnson- THE INTERNATIONAL STYLE- ARCHITECTURE SINCE 1922. Image via www.modernism101.com Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes / Various Architects. Image © Wikimedia user François GOGLINS (Public Domain)

Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes / Various Architects. Image © Wikimedia user François GOGLINS (Public Domain) Elements of Architecture Central Pavilion, Model in progress.. Image Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Elements of Architecture Central Pavilion, Model in progress.. Image Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia VILLUM Window Collection. Image Courtesy of Copenhagen Architecture Forum Copenhagen Architecture Forum (CAFx)

VILLUM Window Collection. Image Courtesy of Copenhagen Architecture Forum Copenhagen Architecture Forum (CAFx) © Festus Jackson-Davis

© Festus Jackson-Davis