Over the past 20 years, Vancouver Island author Robin Stevenson has written more than 30 books for young readers.

One of her preschool storybooks, Pride Puppy, is an alphabet book that follows a family as they search for their lost dog at a Pride parade.

She never expected the story to end up at the U.S. Supreme Court.

The book landed there after a group of parents from Maryland sued the Montgomery County Public Schools Board of Education in 2023, claiming the use of Pride Puppy — as well as eight other queer-inclusive books — in public school classrooms violated their religious freedoms, and they should be able to opt their children out of classes featuring such books.

Portrait of Vancouver Island author Robin Stevenson. (Submitted by Robin Stevenson )

Portrait of Vancouver Island author Robin Stevenson. (Submitted by Robin Stevenson )

This summer, the court sided with the parents, awarding them a temporary injunction. Schools in the Maryland school district must now alert parents and give them the opportunity to remove their children from class before books with LGBTQ+ content are shared — a rule that critics say could dissuade schools from including queer books at all.

Stevenson fears LGBTQ+ books could soon face a similar fate much closer to home.

Alberta legislation a first for Canada

By Oct. 1, schools in Alberta will have to remove books which include sexually explicit content, according to the province’s education minister, Demetrios Nicolaides. Students in Grade 10 and above will still be able to access content that includes vague depictions of sex — as long as they are deemed developmentally appropriate by the province.

Stevenson said amid a rise in book bans across North America, the planned legislation is disappointing to see in Canada.

“To have it coming from a provincial government, banning books kind of en masse, is hugely concerning,” she said.

The change is about putting rules in place for schools that previously had no standard for selecting age-appropriate books for their libraries, according to Nicolaides.

Stevenson worries that the legislation’s undefined “developmentally appropriate” caveat could be used to restrict queer stories.

“The situation in Alberta is the most serious threat we’ve faced so far to LGBTQ books in [Canadian] schools,” she said.

She says that the sheer number of books in school libraries, coupled with limited fiscal and staffing resources, could mean that books are pulled from shelves without thorough review.

“They don’t have the staff able to sit down and read cover to cover every book in the school library by the beginning of October to see if they’re in compliance with this new legislation or not,” she said.

She’s also concerned that some people in B.C. are pushing for similar kinds of book bans.

Book ban worry spreads west

In June, Surrey Conservative MLA Mandeep Dhaliwal introduced proposed legislation to review all resources, including books and films used in B.C. schools, to ensure their age-appropriateness.

The proposed Parental Transparency and Age-Appropriate Education Act, which ultimately failed to pass, sought to form a public committee tasked with approving all educational material used in B.C.’s public schools.

Last year, individuals challenged 62 books in B.C.’s school and public libraries, according to the Canadian Library Challenges Database. Fourteen of the titles were removed, with the most common reasons being racism or ideological bias. No titles were removed due to queer content.

B.C. educators say books for all

Emily Fornwald, an education librarian at the University of British Columbia, worries that proponents of book bans in British Columbia could be emboldened by Alberta’s move.

She says that having access to diverse books is important for children’s development.

“Reading lots of different stories about lots of different kinds of people is helpful for us in developing our own identity, but also helpful for us developing the ability to connect with other people,” she said.

English teacher and young adult author Tanya Boteju agrees, though she acknowledges that some themes need to be presented with care. She says that the best place to do that is in the classroom, with conversations guided by trained educators.

Tanya Boteju’s book Kings, Queens and In-Betweens is a young adult novel about coming of age in queer communities. (Submitted by Tanya Boteju)

She remembers when, in 2023, RCMP were called in to check if a school library in Chilliwack, B.C., had books containing child pornography, after a complaint was made by Action4Canada, a group that describes itself as committed to protecting faith, family and freedom.

“It doesn’t take much,” Boteju said. “It takes one loud voice to put into question practices that are very thoughtful.”

No child porn was found in the school.

Boteju says provincewide bans or restrictions undermine the pedagogical expertise of teachers and librarians. She doesn’t want to see anything like Alberta’s new rules in B.C.

“This Alberta book ban is really taking away from students the opportunity to learn about things that impact them and the things they’re experiencing, in a safe, educational environment,” said Boteju. “It’s the opposite of keeping students safe.”

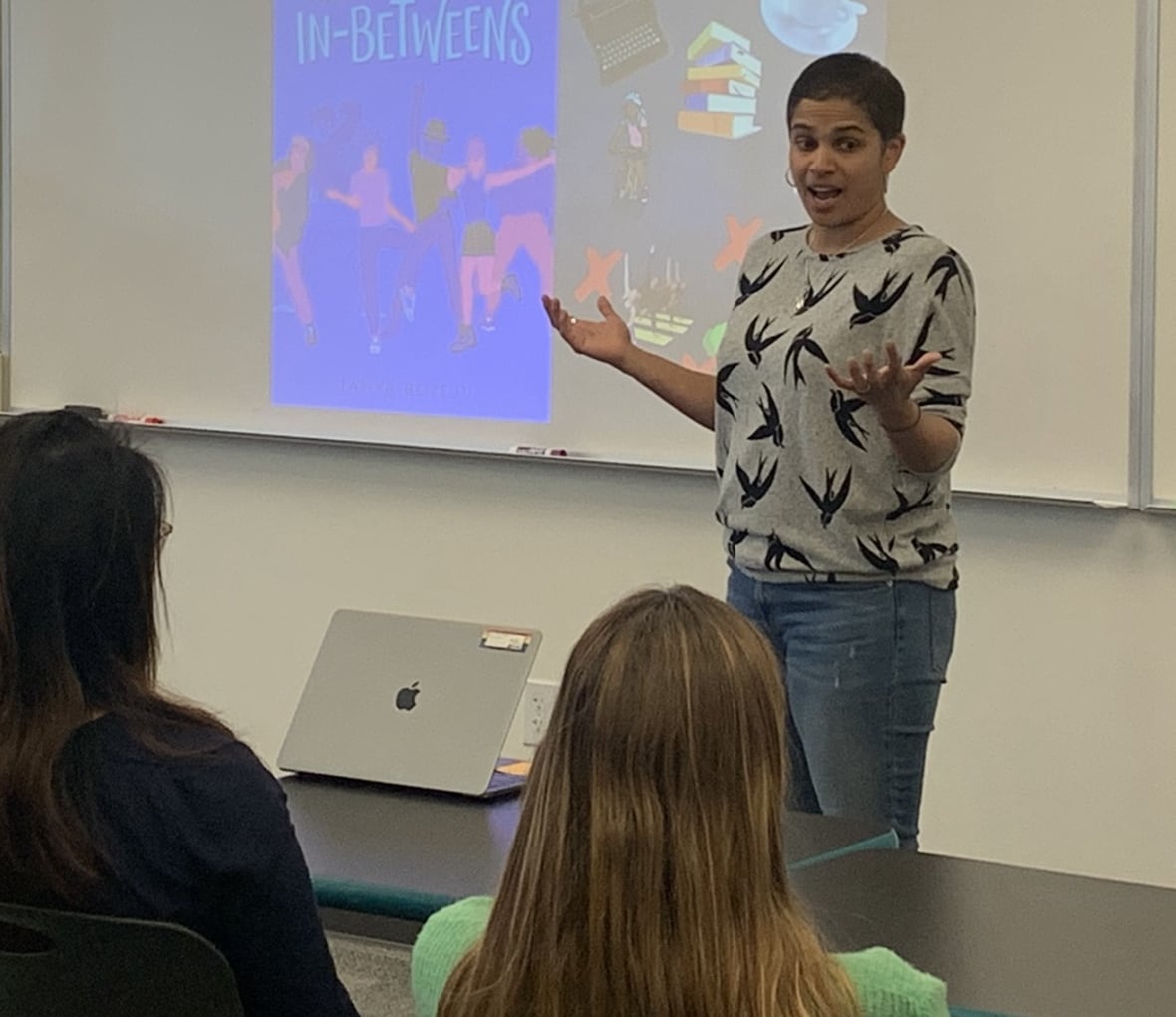

Tanya Boteju discusses her novel Kings, Queens and In-Betweens during a school visit in Vancouver, B.C. (Submitted by Tanya Boteju)

Tanya Boteju discusses her novel Kings, Queens and In-Betweens during a school visit in Vancouver, B.C. (Submitted by Tanya Boteju)

In 2002, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a Surrey school board could not ban LGBTQ+ picture books in order to protect religious values, writing that “tolerance is always age-appropriate.”

For now, Stevenson is hopeful that the book ban won’t go ahead in Alberta.

“All kids deserve to see themselves and see families like their families on the shelves,” she said. “I think there is going to be pushback.”