In the early Noughties, when Sam Sussman entered the awkward age of adolescence, nearly every person he encountered asked him the same question: “Do you know who you look like?” Based on the curve of his mouth, the arc of his nose, the contours of his eyes, and the kinks in his hair, every one of them answered their own question: “Bob Dylan.”

“At first it was thrilling,” says Sussman, who is now 34. “Who doesn’t want to be told they look like a cultural icon?” A few years later, however, when bits of information about his past began to come to him, “the situation became much more volatile and complex. I just didn’t want to have that conversation with people any more.”

In fitful and often fraught exchanges, his mother Fran had begun doling out stories from a past she shared with Dylan that often invited more questions than answers. Over time, Sussman pieced together the outlines of a relationship between them that, while fleeting and distant, was, at least for him, potentially profound. He wrote about their liaison, and the surprising and complex role it has had in his life, in a celebrated essay published by Harper’s Magazine in 2021. In the piece, he pondered whether Dylan was, in fact, his father, a speculation that drew a terse “no comment” from the musician’s team when the magazine reached out to them. But as important as Dylan’s role was to Sussman’s story, his true focus turned out to be his mother and the mysteries surrounding his birth that she left unsolvable when she died of ovarian cancer at age 63 in 2017.

The success of the Harper’s piece inspired Sussman to reimagine his story as a novel, his first, to be published this month: Boy from the North Country. The title refers both to the similarly named Dylan song and the author’s time growing up with his mainly single mother in a town 60 miles north of New York City. Though readers of the essay encouraged Sussman to write his story as a memoir, he was determined to tell it in novel form. “Memoirs are often just read for the story of someone’s life, so the question of how that life was transformed into literature becomes secondary,” he says. “I care much more about becoming an artist on my own terms than I do about just regurgitating the facts of my life.”

Though Sussman tells his story in the novel in the first person, he gave himself and his mother pseudonyms. When asked how much of his book hews to the truth, he offers a joke answer that doubles as a reference to something Dylan said in the 1960s. “There’s a famous interview with him in about ’65 or ’66 where he’s asked, ‘How many folk singers do you consider protest singers?’ Dylan answered, ‘132.’ So, I’ll say 132 per cent of this story is true,” Sussman says with a laugh.

open image in gallery

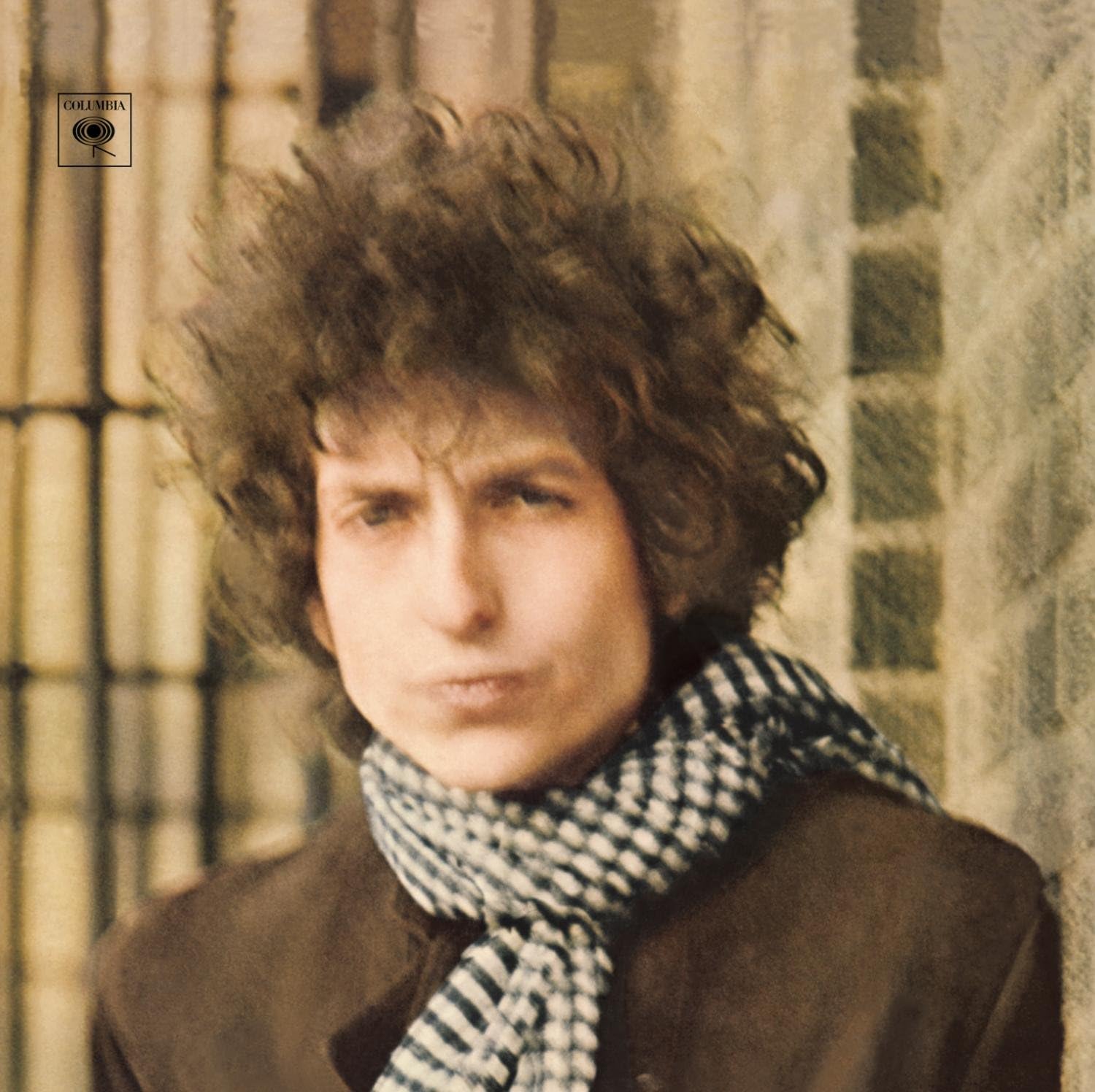

Like father, like son? With his long, frizzy hair forming an auburn halo, Sussman can’t help but appear like a living, breathing diorama of Bob Dylan from the ‘Blonde on Blonde’ album cover (Columbia)

His prose in the novel has a journalistic precision, elevated by the grace of his language and the depth of his connection to the parent who raised him. To Sussman, the act of transforming his experience into art mirrors the experience of both Dylan and his mother in the period when they met. In 1974, when Fran was 20, she dropped out of the prestigious Bennington College and moved to New York to study acting at the famed school run by acting coach Stella Adler. She also took a painting class at that time with the forbidding artist Norman Raeben, the youngest child of the acclaimed Yiddish writer Sholom Aleichem.

It was there that she met Dylan, who arrived at the class one day, without fanfare, to take his place among the other students. Years later, in a 1978 interview with Rolling Stone, Dylan said he had come to the class not only to get feedback on his own abstract paintings but to absorb Raeben’s philosophy about the relationship between art and life. He told the publication that Raeben “put my mind and my hand and my eye together in a way that allowed me to consciously do what I unconsciously felt”. Raeben “didn’t teach you so much how to draw. He looked into you and told you what you were”.

When it came time for the students to critique each other’s work in Raeben’s class, nearly all of them projected their preconceived, and often fawning, notions of Dylan onto his work instead of judging them as distinct creations. An exception was Sussman’s mother, whose honest indifference to his pieces apparently intrigued him. Soon they began meeting up at her postage-stamp-small, one-bedroom flat in a nondescript walk-up in the East 70s of the Upper East Side. Odd a setting as it may have seemed for a superstar, it was perfect for an elusive legend who, above all, wanted privacy and focus. So began their year-long relationship, which Fran would later demurely describe to her son as “dating”. Years later, in the mid-1980s, Dylan got back in touch with her, extending their relationship into the early 1990s, when Sussman was born.

There’s an incredible continuity between the art that Dylan and my mom were each trying to create back then and the book I was trying to write here in the same room

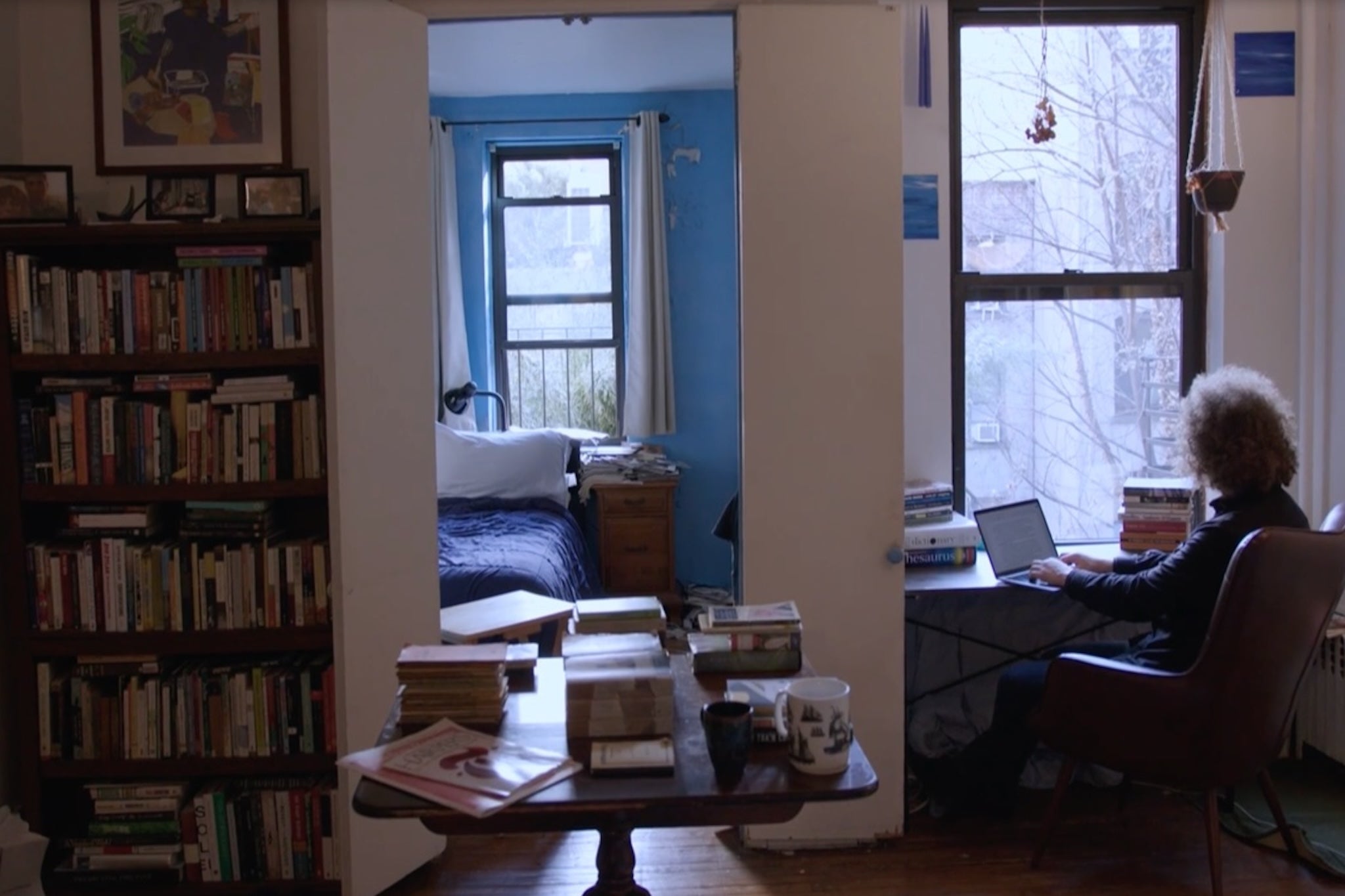

Today, he lives in the same rent-stabilised apartment where Dylan and his mother got together – and that’s where he chooses to do this interview. It’s not hard to tell why he’s attracted to the place, not solely for its history and reasonable rent, but because it offers an ideal refuge for a writer. The pin-drop-quiet apartment is dominated by books and the desk where he spent the last two years writing his. “Places hold memories and meanings, and this one holds many for me,” Sussman says from behind the desk. “There’s an incredible continuity between the art that Dylan and my mom were each trying to create back then and the book I was trying to write here in the same room.” In essence, each of them was trying to clarify their voice through the work they were creating.

Sussman’s physical connection to Dylan makes itself plain instantly. With his long, frizzy hair forming an auburn halo, he can’t help but appear like a living, breathing diorama of Dylan from the Blonde on Blonde album cover. Back in 1974, when Dylan first came to New York City, having recently released his 14th studio album Planet Waves, he was trying to create what would become one of his most profound, pained and personal works, Blood on the Tracks. “Something Dylan is trying to figure out when he’s writing that album is how to relate to the concept of time,” Sussman says. “He came to Norman Raeben’s class because he heard his notion that meaningful art comes when you react to your feelings and experiences and put that into your work. At that time, Dylan was trying to make work that somehow resonated with a younger version of himself as an artist because he felt his best work was back there.”

To Sussman, it’s especially meaningful that the album he created then ranks with his greatest. “It gave me the chance to write about deeper themes,” he says. “Readers who love Dylan will have the extraordinary experience of sitting beside him while he’s writing one of his most beloved albums.”

open image in gallery

An apartment of memories: Sussman pictured at his writing desk at his mother’s New York City apartment, where Bob Dylan was a frequent visitor (Courtesy of Sam Sussman)

In his book, Sussman’s character tries to imagine Dylan’s artistic goals with Blood in order to get a better understanding of his mother’s connection to him. In the process, he winds up doing some of the work of a music critic, providing analysis fans of the bard may well appreciate.

The album’s opening track, “Tangled Up in Blue”, features the only direct lyrical reference to Sussman’s mother by alluding to a book she gave him by the poet Francesco Petrarch. Dylan sings:

She opened up a book of poems

And handed it to me,

Written by an Italian poet

From the thirteenth century.

And every one of them words rang true

And glowed like burnin’ coal.

Pourin’ off every page

Like it was written in my soul

From me to you,

Tangled up in blue.

As important as Dylan is to the story, Sussman made sure not to overemphasise his role, the better to stress that the spiritual and emotional centre of the story lies elsewhere. “I would be a shallow person if the centrepiece of my identity was a relationship with someone I don’t know,” he says. Instead, the focus remains on his life with his mother, both when he was growing up and the incredibly painful, final chapter before her death.

The work is between me and the writing desk. It’s also about the emotional life between me and my mother. No success or criticism will ever be as large as those two things

His mother divorced the man Sussman was told was his father when he was still a child. Afterwards, there were men in her life, many of them troubled by trauma. Fran had plenty of her own, having experienced sexual violence several times. “She was someone who had been through a great deal of suffering and had transformed that into a life that was meaningful and filled with love,” Sussman says. “I think she hoped she could heal these men as she had healed.”

She employed those skills in her profession as a therapist, often working with abused women. Having abandoned a potential career in the arts when she left New York in the 1970s, she discovered that being a therapist could be an art unto itself. It was she who ended the relationship with Dylan, essentially “ghosting” him to live a life unobstructed by a man of overwhelming power. It didn’t hurt in her decision that Dylan was married at the time to the former actor and model Sara Lownds, whose difficulties with him inspired many songs on Blood. He also had other girlfriends at the time.

His mother never talked about any of this with Sussman when he was a child. The first person to press his striking resemblance to Dylan was a teacher he had when he was 13, who suggested he check out his music. At the time, Sussman was listening to what most kids of his generation were, but he found something deeper in Dylan. “He was a storyteller rooted in a narrative tradition that’s biblical, that’s mythic, that’s American,” Sussman says. “It was so much larger than the culture of my generation.” Fran’s record collection contained all the usual 1960s touchstones by The Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel, but no Dylan, a telling oversight for any person of taste from her generation.

open image in gallery

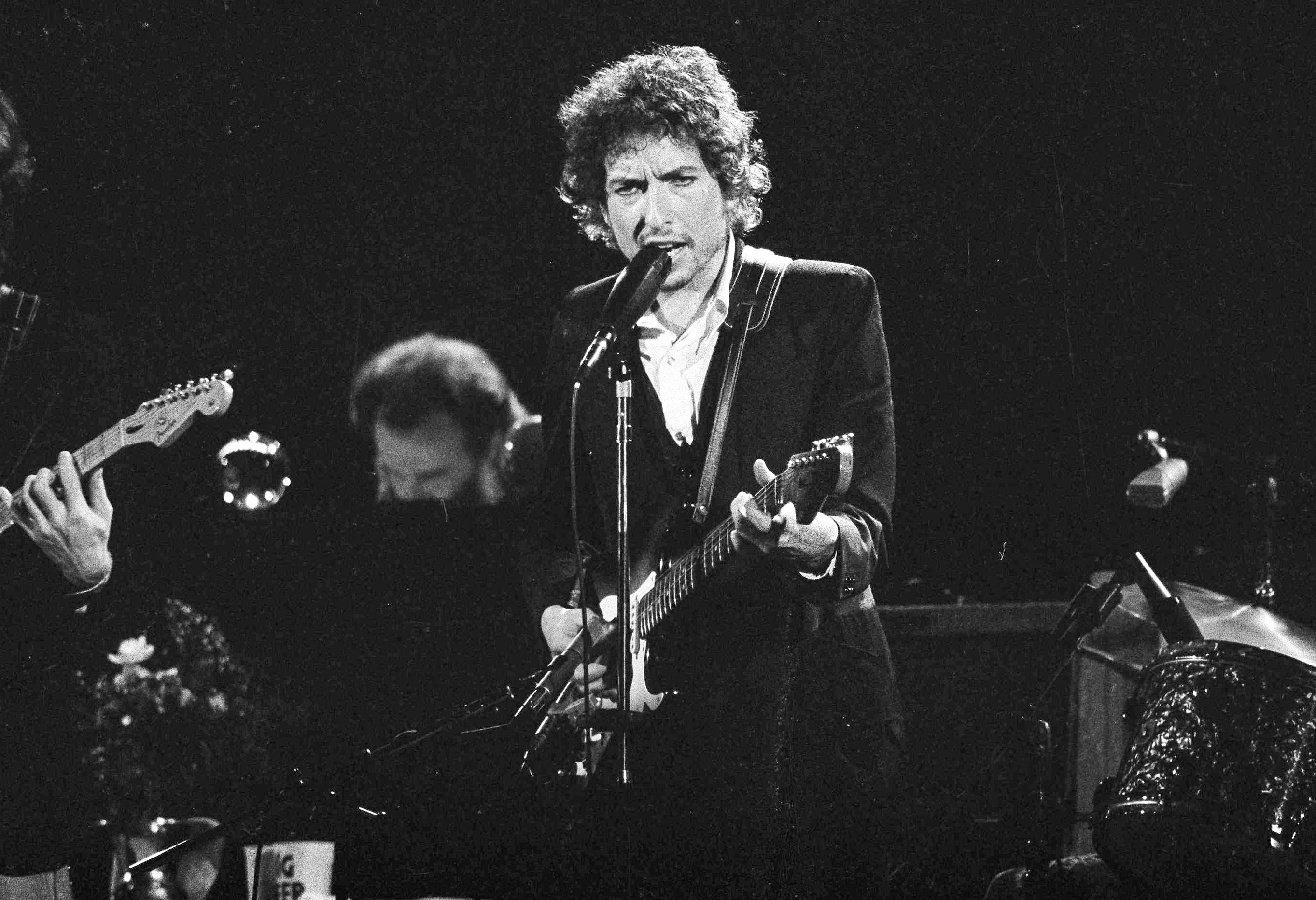

Dylan on stage in 1974, the year he first came to New York and met Sussman’s mother (AP)

As he grew, Sussman aspired to become a writer. After graduating from Swarthmore College, he moved to England, where he earned an MPhil from the University of Oxford and, later, taught writing in the UK. His novel begins with the true story of him returning home to help Fran as she went through an agonising series of chemotherapy for her cancer. In Sussman’s original essay, he wrote about the effect his mother had on him, but only in the novel does she arise as a fully formed character. That was a key goal for him, but the arduous process of capturing that meant reliving an often horrific period in both of their lives. “I think I had to write this book, in part, to make sense of that,” he says.

He went about it in a pure way, writing the novel on his own, without a publisher in place who might pressure him to push the Dylan angle beyond what he believed was fair. In the story, as in real life, his mother often evaded questions about his lineage, though she did eventually reveal enough to satisfy a reader. What she chose to withhold from him, and what his character comes to learn from that decision, winds up having a key emotional payoff in the book. Told as fiction, Sussman’s story expands to become a statement about identity in general. “I want the reader to have a similar journey to mine in some ways,” he says. “We have such great choice in how to define who we are.”

open image in gallery

What’s in a name? The title of Sam Sussman’s book is a reference to Dylan’s 1963 track ‘Girl from the North Country’ (Grove Press/Atlantic)

Sussman says he’s unconcerned with how readers will react to a story connected to an artist millions take deeply personally. “The work is between me and the writing desk,” he says. “It’s also about the emotional life between me and my mother. No success or criticism will ever be as large as those two things.”

As for Dylan, Sussman says he has no desire to connect with him or hear from him about the book. On what he would want from him if they were ever to meet, Sussman says, “just to talk to him about my mother because I don’t know many people who knew her in that period”.

The one person whose reaction to the book he has most deeply considered is his mother’s. “If she could read the book, I would hope she would feel two things,” he says. “The first is that she would feel that I honoured the complexity of her life and who she was.” The second, Sussman says, is “that she would feel that I’ve made a meaningful life after her death, one that honours the values with which she raised me. Every day when I wrote, I had that on my mind.”

‘Boy From the North Country’ is out on 2 October via Grove Press in the UK and Atlantic Books in the US