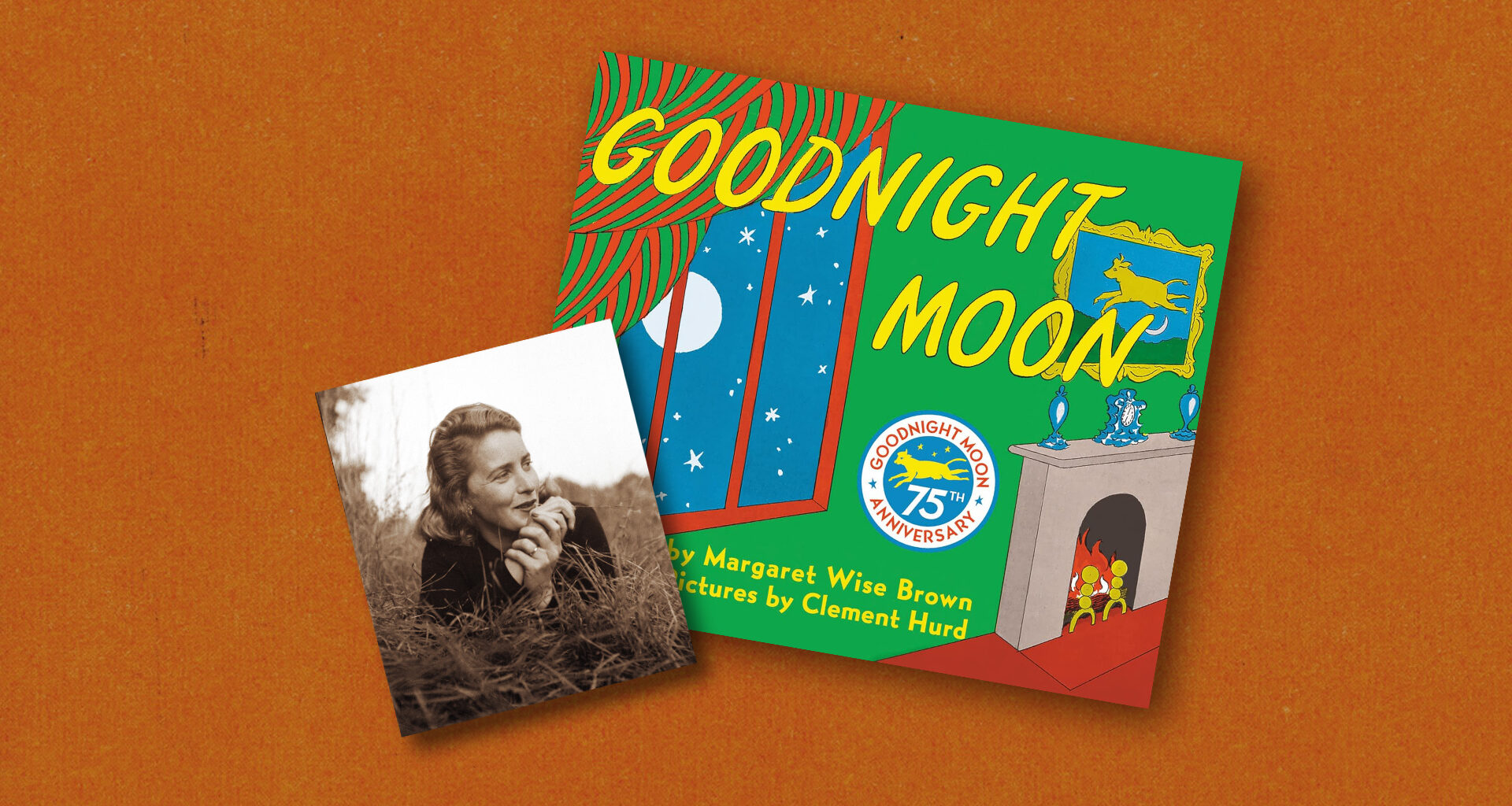

September 3, 2025, marks the 78th anniversary of the publication of Goodnight Moon, one of the best-selling picture books of all time (more than 50 million copies sold).

Author Margaret Wise Brown (1910–52), who wrote more than 100 picture books, never saw the book’s massive success. But her influence, and Goodnight Moon’s unexpected popularity after her untimely death, are at the epicenter of what one historian called the “shapeshifting influence of American progressive educators on the invention of books for children” in the 20th century.

Writer of Songs and Nonsense

Amy Gary’s biography of Brown, In the Great Green Room: The Brilliant and Bold Life of Margaret Wise Brown, depicts not merely a life of literary giftedness and ambition but a restless soul whose search for love and meaning ended tragically early.

Brown wrote unceasingly for children, including children’s music. In her will, she requested her tombstone be etched with the simple epitaph “Margaret Wise Brown. Writer of Songs and Nonsense.”

This single phrase encapsulates the tension of her life—a life dedicated to creating imaginative worlds for children while grappling with a deep sense of autonomy and personal meaninglessness. She never married or had children, instead living a bohemian life in New York City filled with myriad affairs with both men and women.

Story of ‘Goodnight Moon’

The idea for Goodnight Moon came to Brown in a dream. She was experimenting with “the sleep-inducing qualities of words and poetry” for bedtime.

Brown was dedicated to creating imaginative worlds for children while grappling with a deep sense of autonomy and personal meaninglessness.

Goodnight Moon was a follow-up to the successful The Runaway Bunny (1942), but when Goodnight Moon was released in 1947, it barely registered an audience. In 1953, a year after Brown’s death, it sold just 1,500 copies. By 1970, however, it was selling 20,000 copies a year. By 2007, sales had skyrocketed to 800,000 annually. Today, various editions sell more than 1 million copies every single year.

The book’s delayed success is hard to explain, but I find it interesting that its rise in popularity coincided with a decrease in Christian faith and practice.

Secular Prayer

In Christian communities for generations, children have been encouraged to find comfort in the routines of bedtime prayers to a God whose transcendent presence holds all things together. Bedtime prayers reassure children they can rest in God. When children feel scared and alone, they can remember that “he who keeps watch over Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep” (Ps. 121:4).

Goodnight Moon, on the other hand, is “less a story than an incantation”—an end-of-day liturgy without transcendence. The simple, gentle text and repetitive structure riff on the ritual and reassurances of bedtime, but the objects in the room (mice, mittens, kittens, etc.) are bereft of transcendent significance.

It’s a soothing alternative to traditional Christian bedtime prayers: a secular “prayer” that finds peace in the eclectic wonders of immanence, in the rhythmic cycles of nature (the moon’s nightly illumination) rather than in the love and sovereignty of God.

Instead of appealing to a God who holds all things together in his ordered creation, the liturgy of Goodnight Moon simply observes the randomness of an inexplicable universe: Goodnight nobody. Goodnight mush.

Wounded, Restless Heart

Brown’s longest romantic relationship was with Blanche Oelrichs, an older woman who wrote under the pen name Michael Strange. It was a secret affair that ended in a heartbreaking rupture. As Gary notes in In the Great Green Room, Oelrichs, facing the onset of leukemia, “decided her attraction to Margaret was a sin. . . . If they were really Christians [as they both professed to be] then they should be able to fight their desire to be together physically.”

Oelrichs cut off the relationship with Brown, who “grew angry” and “wrote letter after letter . . . defending the nature of their love.” The pain of this rejection left Brown wounded—a wound she’d seek to heal in a final, short-lived romance.

In 1952, just months before her death, Brown fell in love with James “Pebble” Rockefeller Jr., a recent college graduate 20 years her junior. Their engagement marked a new chapter, but her existential despair was far from settled. Pebble would later recall a moment when she turned to him, eyes gazing far off, and said, “We are born alone. We go through life alone. And we go out alone.”

This sense of isolation echoes in what was Brown’s final (and autobiographical) children’s book, Mister Dog, which tells the story of Crispin’s Crispian, a dog who “belonged to himself.” The book’s moral: Autonomy is the highest good.

Sudden Death of a Secular Saint

In a bizarre twist of poetic tragedy, Brown’s life came to an abrupt end while alone in France at the age of 42. Brown was on her way to a rendezvous with Pebble when she was rushed to a Catholic hospital, staffed by nuns, for an emergency appendectomy. After the procedure, a nurse asked her how she was feeling. As she answered, Brown kicked up her leg in a carefree cancan gesture. The act dislodged a blood clot that led to a fatal pulmonary embolism.

In a final act of nonsense, Brown made a theatrical exit from a life lived on her own terms.

Goodnight Moon simply observes the randomness of an inexplicable universe.

Today, Brown is lionized as a secular saint. She’s remembered as a restless, rebellious radical, whose New York City writing studio is considered an LGBT+ historic site.

Goodnight Moon’s lonely child motif matches Brown’s life. Her final words to her last lover (“We go out alone”) reflect a life lived outside the lines.

Point for Christian Parents

Here’s the point for Christian parents. Goodnight Moon reads like a bedtime prayer for a reason. Brown’s experimental writing was part of a modernist movement to shape an alternative moral ecology for children. Many of her books are, perhaps unwittingly, examples of what Philip Rieff memorably coined “deathworks”—objects of art intended to make the moral imaginary of traditional values look unimportant, even ridiculous.

The next time you read Goodnight Moon with your kids at bedtime, don’t stop at “goodnight noises everywhere.” End your routine with bedtime prayers. Observing the diverse wonders of the wide world—even the small world of a green bedroom—is a good practice. But observing these wonders should lead us to worship the God who created it all, sustains it, and gives it meaning.

As for the runaway sheep in that French hospital room, I hope that in her last minutes of life, a kind nun spoke gospel truth to her restless heart. What Brown needed was not a quiet old lady whispering “hush” but a slumberless Shepherd whispering “mine.”