There is one fact that nearly everyone—prominent investors, leading international economists, and top think tanks—tend to get wrong: the direction of capital flows during the global financial crisis (which is probably better understood as the North Atlantic financial crisis, as its epicenter was in the United States and in European banks investing in the US mortgage market)

More From Our Experts

Because the dollar (somewhat surprisingly) rallied during the crisis, there is an assumption that foreign investors moved funds into the U.S. This is a key part of the classic claim that the dollar is the ultimate “safe haven” asset: it rallied even when the United States is the source of the underlying financial trouble (See a recent column by the FT’s Robert Armstrong).

More on:

An example of the pervasiveness of this argument comes from Adam Posen, head of the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), in the most recent issue of Foreign Affairs:

“When U.S. markets directly triggered a worldwide recession in 2008, interest rates and the dollar fell and then rose together as capital from abroad flowed into the U.S. market.” (emphasis added)

Follow the Money

Brad Setser tracks cross-border flows, with a bit of macroeconomics thrown in.

Alas, that isn’t quite true.

I am a bit of a stickler when it comes to the balance of payments data.

More From Our Experts

And a careful fact check would show that capital from abroad—unambiguously—flowed out of the U.S. market in late 2008.

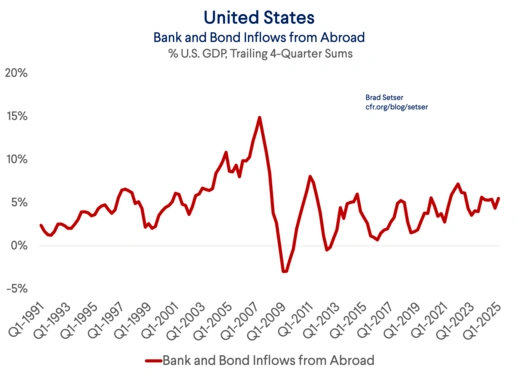

Consider the following chart, which shows the sum of foreign purchases of U.S. bonds and foreign inflows into the U.S. banking system. Those flows peaked prior to the crisis in 2007 and turned negative in 2008.

More on:

The disaggregated chart tells a clear story of reduced foreign demand for U.S. assets amid the crisis. Bond inflows fell off a cliff but, technically, foreign bond investors were still putting money into the U.S. in 2008. But foreign investors were also, understandably, withdrawing funds from the U.S. banking system. That led to a full reversal of net debt creating flows from abroad.

.png.webp.webp)

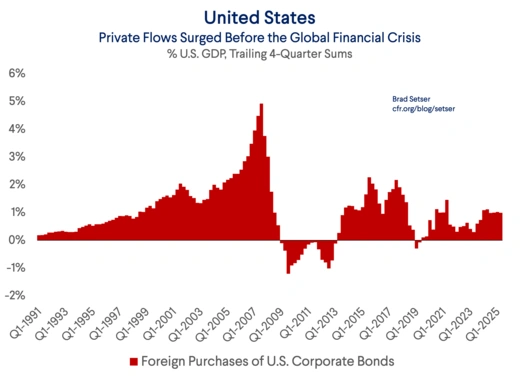

If you just look at a measure of private foreign demand for bonds, such as flows into U.S. corporate bonds (which includes asset-backed securities such as, of course, mortgage-backed securities), those flows absolutely reversed during the crisis.* The bid for U.S. bonds in the crisis came from central banks seeking the safety of the Treasury market, not private investors.

So, why then did the dollar rally?

The answer is quite simple: while foreign capital fled the U.S., U.S. capital also fled global markets and returned home in 2008.

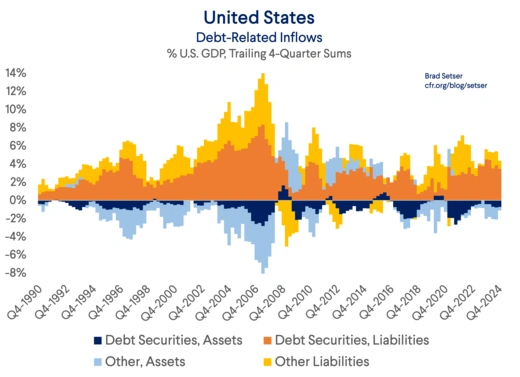

(Note the blue bars in the graph below, which show U.S. money coming home—the positive inflow is from bringing funds previously invested abroad back home.)

It was the full reversal of capital flows and return of U.S. money to the U.S. that produced the bid for dollar assets.

U.S. money market mutual funds that had lent to foreign (mostly European) banks wanted their money back, famously.

And American banks that had lent out dollars to carry traders betting on the continued decline of the dollar relative to (then high yielding) emerging economies also wanted their money back.

Put differently, the dollar was one of the funding currencies for a host of carry trades prior to the global financial crisis, as the dollar had been in a sustained slump and U.S. rates were relatively low. The dollar, as well as the yen. It is not a coincidence that the yen also rallied during the global financial crisis.

That to me is a critical clue. Most attribute the ‘08 yen rally to a carry unwind, rather than a bid for the yen as a “reserve” currency. That could be said for the dollar as well.

Why does all this matter? Well because a lot of financial models now assume, incorrectly I think, that the dollar will rally in the event of future financial instability—say, a selloff in U.S. equities or credit. That makes it easier for investors to continue to hold dollar assets unhedged.

The logic of the argument goes a bit like this—sure, my fund is very overweight U.S. financial assets because of the “dominance” of the U.S. in global equity indexes right now, but that risk is partially offset by the natural hedge provided by the dollar, as the dollar often rallies into bad news. The dollar thus will likely rally in the event of a significant equity market correction (as it did in ‘08 or, for very different reasons, 2020), and hedging dollar risk effectively means undoing a natural hedge.

Conveniently the expectation that the dollar serves as an equity (or credit) market hedge based on past correlations also increases current returns, because it provides a reason not to hedge U.S. market exposure at a time when hedging is expensive.**

There is risk, however, that past correlations won’t hold.

If the dollar rallied in 2008 not thanks to its reserve currency status but rather because the funding currencies in a carry trade tend to rally in a carry unwind (and that destination currencies in carry trades tend to selloff), investors should not assume that the dollar will rally in future instability.

One thing is absolutely clear: the U.S. is currently on the receiving side of most carry trades.

The U.S. exceptionalism trade is fundamentally about the expectation of exceptional returns on US assets. That is much more about “carry” than about “safety.”

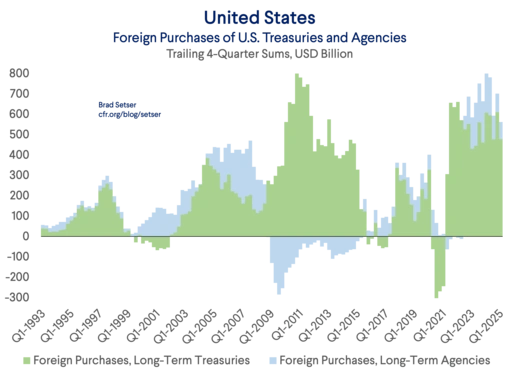

To be sure, there was a “safe haven” bid for Treasuries in 2008, as investors—including official investors—fleeing the U.S. and European banking systems and/or securities backed by U.S. housing (including the Agencies) moved into the safety of Treasuries.

But this is a fundamentally different flow. Rather than and inflow of global capital to U.S. markets, this was a flow out of on U.S. dollar assets into another (Treasuries) as investors didn’t trust the banks or the Agencies.

In fact, in 2008, the run was primarily into short-term bills.

Details, sure—but it is important to get details right!

* Before the global financial crisis, Treasury and Agency demand largely came from central banks. This was the era of peak currency manipulation and official flows.

** Most hedges are relatively short-term, and in turn are a function of short-term interest rate differentials. Right now, the U.S. is a high yielder relative to G10 creditor currencies, and relative to Asian creditor countries like Korea and Taiwan.