The Anatomy of the Architectural Book / André Tavares. Image © Dafne Editora

The Anatomy of the Architectural Book / André Tavares. Image © Dafne Editora

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1033609/the-architect-as-writer-expanding-the-discipline-beyond-buildings

Architecture has always been more than bricks and mortar. It is equally constructed through words, ideas, and narratives. From ancient treatises to radical manifestos, from technical manuals to poetic essays, the written word has served as a spatial, pedagogical, and political tool within the field. Writing shapes how architecture is conceptualized, communicated, and critiqued — often long before, or even in the absence of, physical construction.

Historically, figures such as Vitruvius, Alberti, and Palladio employed writing to codify principles, project ideals, and legitimize architecture as a discipline. In the modern era, Le Corbusier, Adolf Loos, and Lina Bo Bardi wrote prolifically to expand the scope of architecture beyond form and function, often using publications as tools for persuasion and experimentation. The postwar period gave rise to new editorial strategies, as evident in the manifestos of Archizoom and Superstudio, and the polemical publications of Delirious New York and Oppositions, where writing served as both critique and project.

Today, architectural writing is published across a range of platforms, engaging voices from editors, theorists, practitioners, and students. In this way, writing continues to operate as a core architectural practice, not as a supplement to building, but as a means of constructing the discipline itself. In an increasingly interdisciplinary field, where architecture is often practiced beyond the construction site, writing offers a space of projection, critique, and invention, a way of imagining, organizing, and ultimately shaping the built and unbuilt world.

Related Article Architecture and Communication: Dissemination, Curators and Architecture News Architecture’s Written Foundations

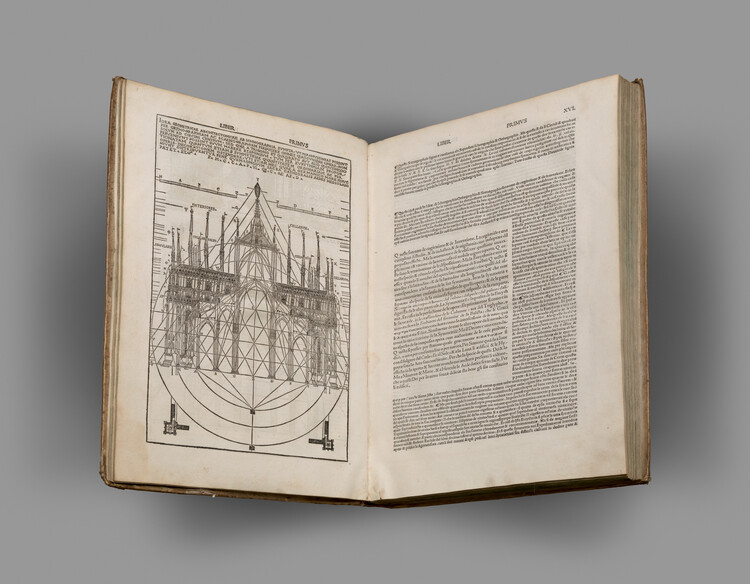

Long before architecture became a profession, it was a literary endeavor. In the absence of formal institutions, writing served as the primary means of consolidating and transmitting architectural knowledge. Vitruvius’s De Architectura is the only architectural treatise to survive from antiquity. Far from being a technical manual, it proposed architecture as a learned discipline grounded in three essential qualities: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas. These principles, abstract yet actionable, offered a framework for understanding the built environment that would shape centuries of architectural thinking.

Vitruvius’s De Architectura . Image via Wikipedia under CC0

Vitruvius’s De Architectura . Image via Wikipedia under CC0

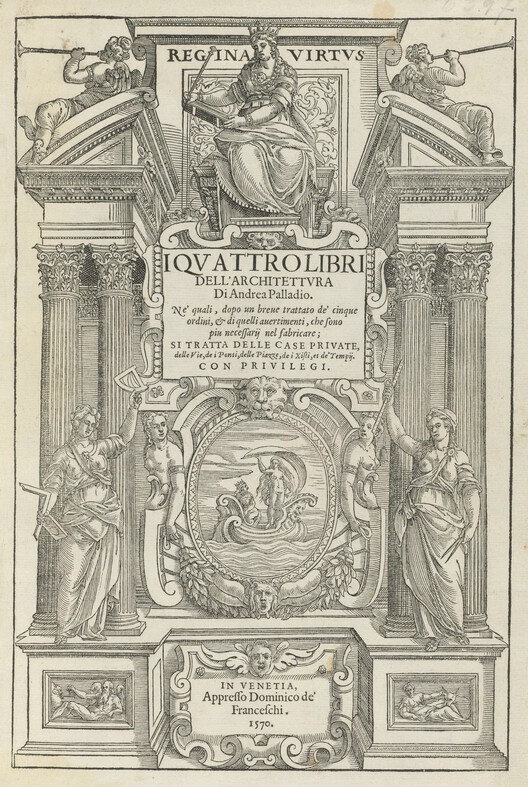

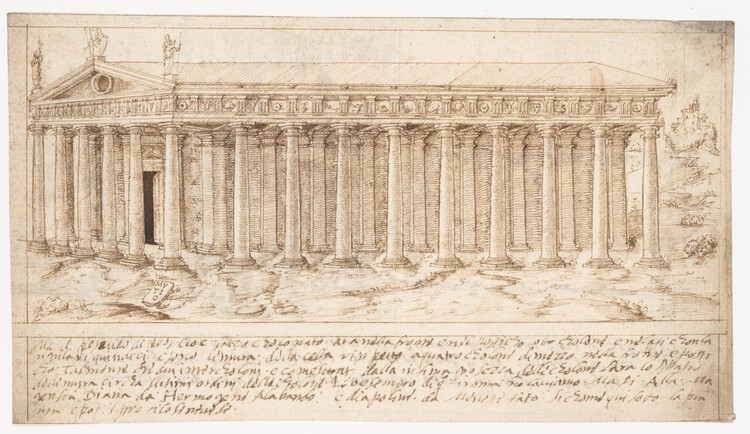

Rediscovered during the Renaissance, Vitruvius’s text became the cornerstone of architectural theory. It offered a link to the classical past and, more importantly, a model for architectural authorship. Leon Battista Alberti followed this path with De Re Aedificatoria, the first major architectural treatise of the Renaissance. Written in Latin and structured in ten books — in deliberate echo of Vitruvius — Alberti’s treatise outlined construction methods, material knowledge, philosophical reflections on beauty, proportion, and the social role of architecture. His work would soon be followed by a wave of influential texts that formalized the visual and compositional language of architecture, establishing canons that would shape built environments: Sebastiano Serlio’s Tutte l’opere d’architettura et prospetiva, Andrea Palladio’s Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola’s Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura.

Andrea Palladio, Quattro Libri dell’Architettura. Image via Wikipedia under Public Domain

Andrea Palladio, Quattro Libri dell’Architettura. Image via Wikipedia under Public Domain

The architectural treatise shaped the discipline by prescribing formal orders and by establishing its intellectual legitimacy and reinforcing its cultural authority. In codifying rules, setting standards, and constructing coherent bodies of knowledge, these publications helped define what architecture was. In a way, they laid the groundwork for what would later be called architectural “style.”

Vitruvius’s De Architectura . Image via Wikipedia under CC0

Vitruvius’s De Architectura . Image via Wikipedia under CC0

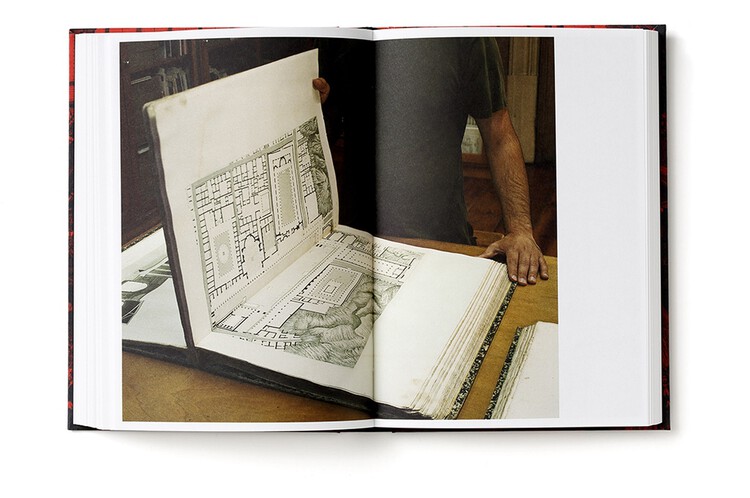

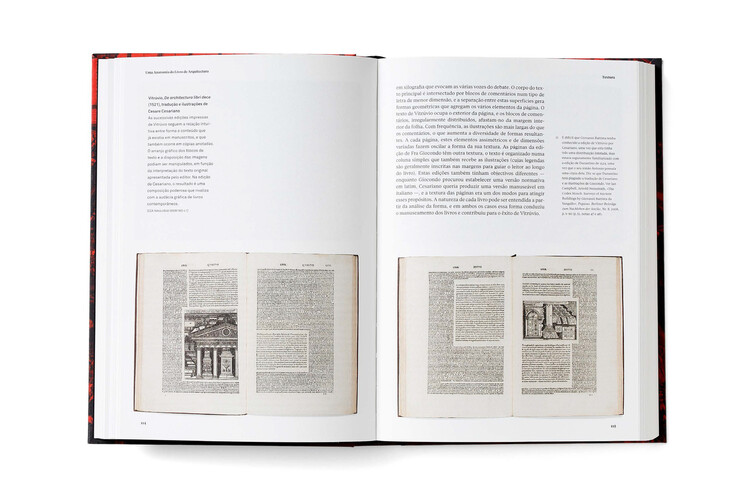

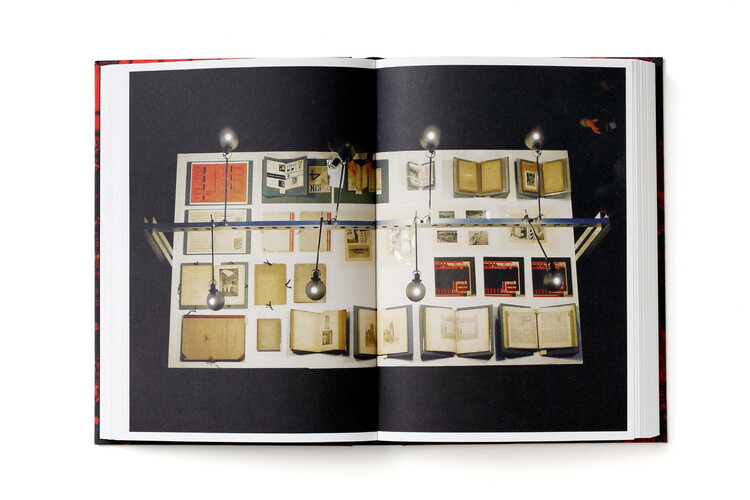

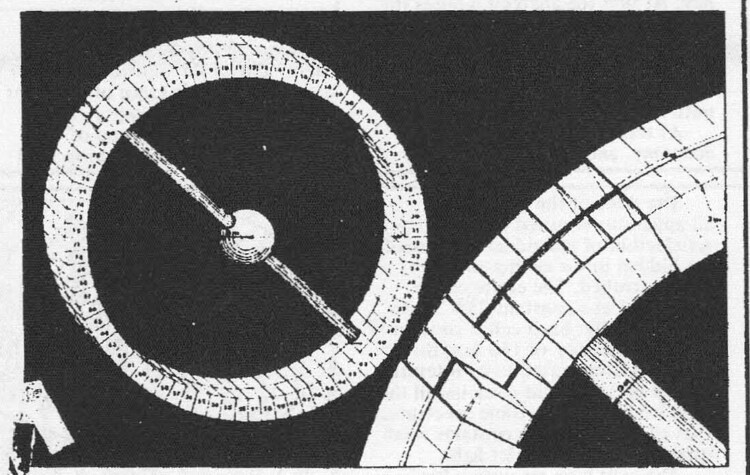

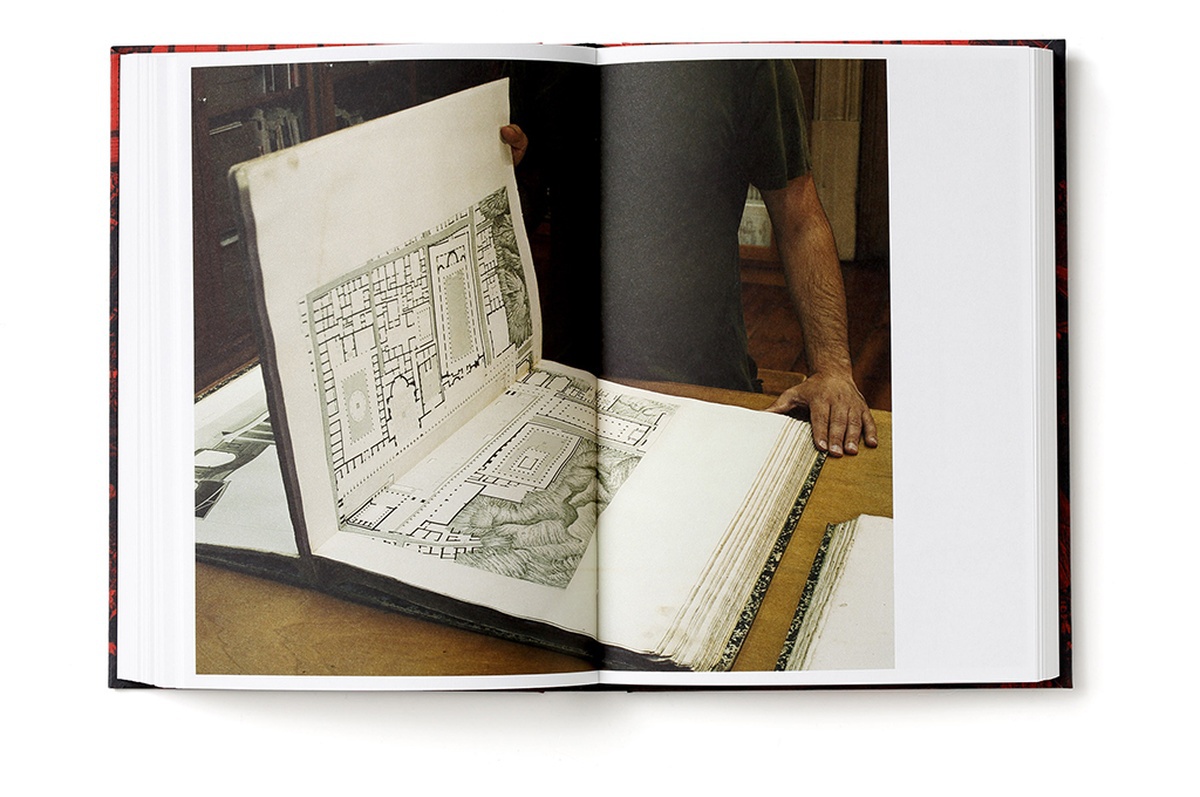

With the advent of the printing press, architectural knowledge became portable and reproducible, enabling principles to travel across regions and generations. In The Anatomy of the Architectural Book, André Tavares shows how the book itself became a site of architectural construction — not just in its content, but in its typographic layout, structure, sequencing, and graphic language. For Tavares, architectural books are both vehicles for ideas and constructions in their own right, where the organization of the page mirrors the organization of space. Writing, editing, and printing thus became operative tools — a form of architectural labor unfolding in parallel with, and sometimes in advance of, the building site.

The Anatomy of the Architectural Book / André Tavares. Image © Dafne Editora

The Anatomy of the Architectural Book / André Tavares. Image © Dafne Editora

Seen through this lens, architectural writing was never just descriptive or explanatory. It was projective. It set the terms of architectural debate, it constructed stylistic canons, and it enabled the transmission of ideas across geography and time. At a moment when architecture is once again expanding into hybrid and interdisciplinary territories, the legacy of the treatise reminds us that writing has always been a primary space of disciplinary construction.

Architecture on the Page

With the advent of modernity, architects increasingly turned to manifestos and essays to challenge the status quo and reshape the discipline. These texts were not neutral commentaries; they were projective devices, tools to imagine and provoke new ways of thinking, building, and inhabiting space. Writing became a medium of design.

The Anatomy of the Architectural Book / André Tavares. Image © Dafne Editora

The Anatomy of the Architectural Book / André Tavares. Image © Dafne Editora

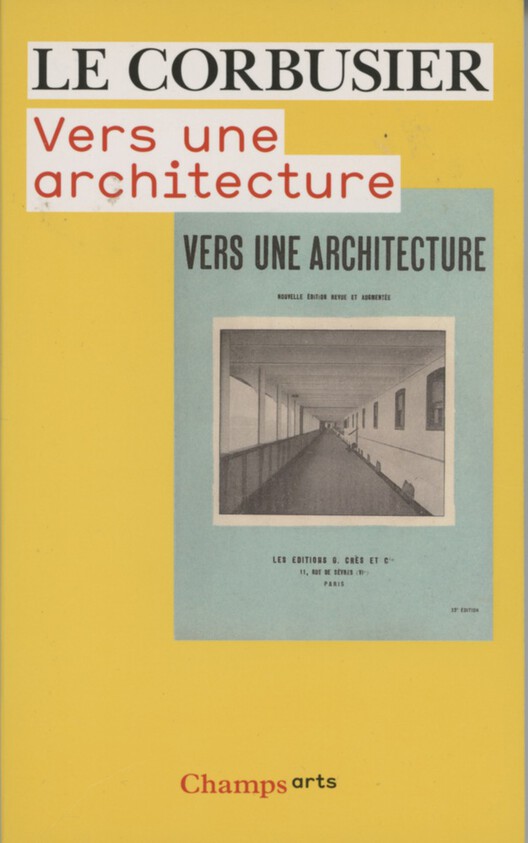

Perhaps no modern architectural text embodies this more than Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture. The book consolidated a series of essays into a coherent vision for a new architecture aligned with the machine age. Le Corbusier declared “a house is a machine for living”, calling for a radical break with historical ornament and a turn toward efficiency, standardization, and clarity. Its impact was immediate and widespread. Reyner Banham would later write that Vers une architecture exerted more influence over the direction of 20th-century architecture than any other architectural work published in the century. The manifesto framed not just aesthetic preferences, but a new ethic, one that recast the architect as a modernizer and cultural agent.

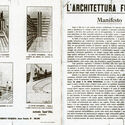

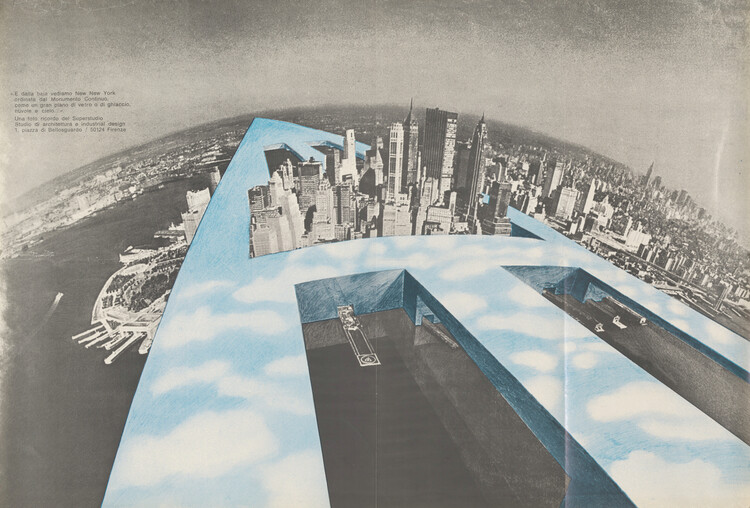

This use of writing as provocation and projection intensified in the 1960s and 70s, as radical architecture collectives questioned not just form, but the entire logic of architectural production. Groups like, Archizoom, and Superstudio treated manifestos as their own form of spatial practice. Their work emerged as a direct response to consumer society, late capitalism, and the failures of modernist planning. Rather than proposing individual buildings, they produced speculative texts, collages, and “paper architectures”; critical visions that questioned the foundations of the discipline itself.

The 1966 joint manifesto for the Superarchitettura exhibition, issued by Archizoom and Superstudio, openly embraced contradiction, irony, and excess: “Superarchitecture is the architecture of superproduction, superconsumption… the supermarket, the superman, super gas.” It was a direct challenge to rationalist dogmas, advocating for total liberation from convention and embracing a world where architecture could be mutable, ironic, even absurd. These writings were often accompanied by iconic drawings that functioned as both critique and vision, imagining cities not to be built, but to be debated.

The Fourth City, Spaceship City- 1971.. Image Courtesy of Superstudio

The Fourth City, Spaceship City- 1971.. Image Courtesy of Superstudio

In these works, the manifesto became more than rhetoric. It was a form of architectural experimentation — a space where the tools of narrative, satire, image, and theory combined to project new futures. Today, as architecture engages increasingly with interdisciplinarity, performance, and immaterial media, the legacy of the manifesto takes on renewed relevance. Writing remains a way to prototype ideas, mobilize critique, and operate across fields. The manifesto endures not as a stylistic relic, but as a reminder that architecture’s boundaries are as much drawn on the page as on the ground.

Writing as Spatial, Critical, and Political Practice

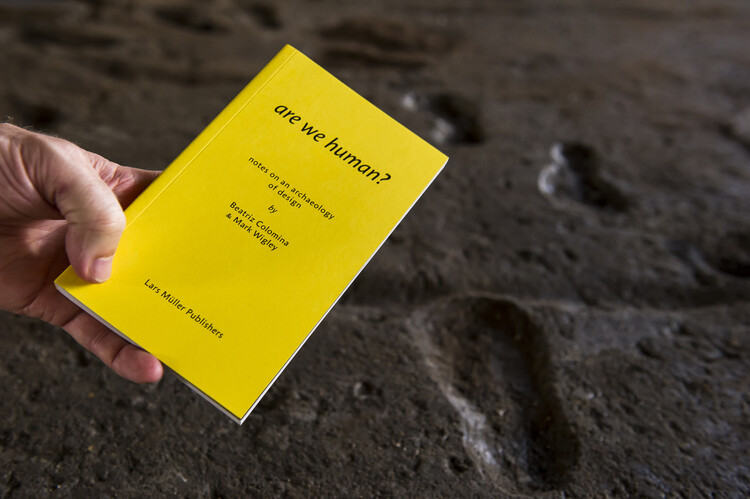

Beatriz Colomina has long argued that architecture is inseparable from its representations. In his publications, she reveals how magazines, advertisements, and editorial platforms are not peripheral to architecture; they are where architecture happens. Colomina shows that print culture has historically shaped how architecture is seen, read, and understood, with the page operating as a conceptual and political space. Writing, in her view, is both projective and critical; it constructs narratives and exposes power structures embedded in built form. The page becomes a conceptual drawing board.

Are We Human?, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley. Image

Are We Human?, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley. Image

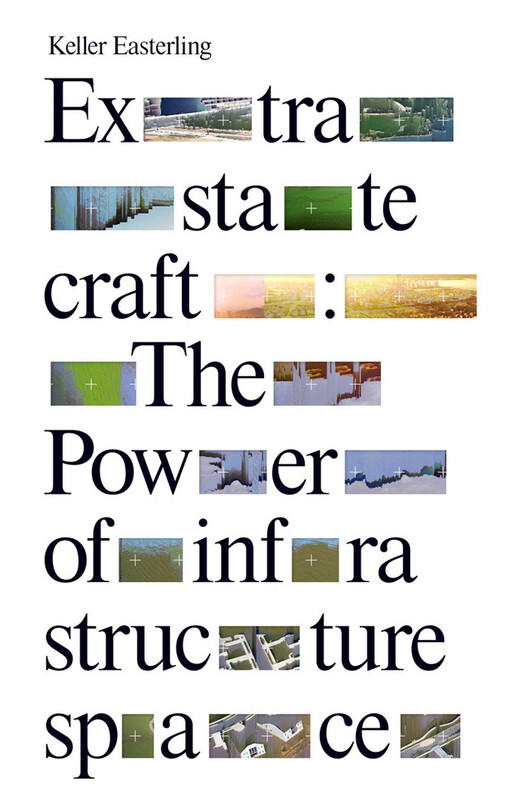

Keller Easterling extends this notion by shifting focus from buildings to systems. In works such as Extrastatecraft and Medium Design, she explores how infrastructure, regulation, and global protocols produce space. Easterling’s practice illustrates that the design of infrastructure often happens through research, text, and diagrams more than through traditional blueprints. By “hacking” global systems with ideas and prose, she expands architecture into the realm of policy, economics, and technology. The written analysis of these systems is itself a mode of design intervention, proposing new forms or revealing spatial conditions that aren’t immediately visible.

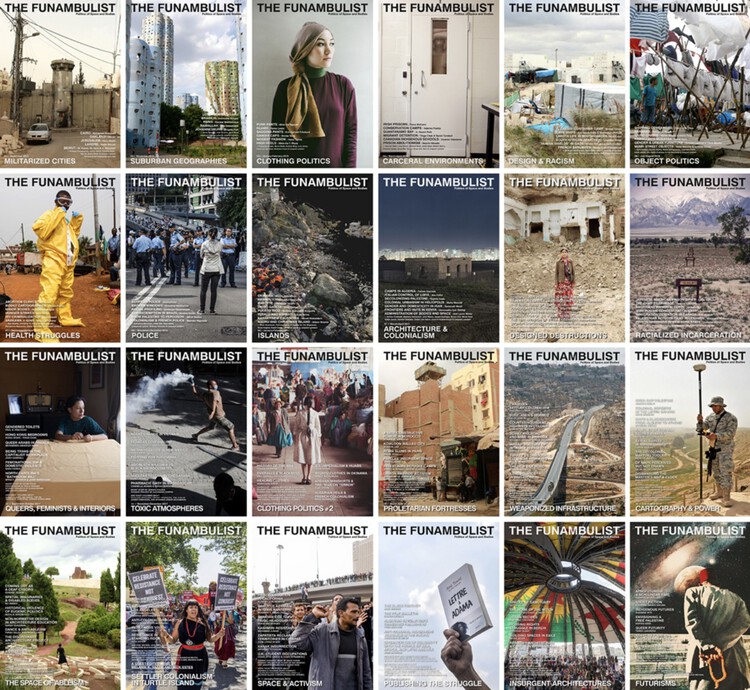

Perhaps most overtly, Léopold Lambert demonstrates writing as a political weapon in architecture. A trained architect turned editor-in-chief of The Funambulist, Lambert uses essays, interviews, and editorials to examine “the inherent violence of architecture on bodies” and its political instrumentality. Through publications like Weaponized Architecture, he analyzes how walls, borders, and urban design enforce power dynamics. Here, writing is deployed to unbuild injustices: dismantling dominant narratives and proposing liberatory ones. This is architecture happening through advocacy and critique rather than construction.

The Funambulist Magazine Issues. Image via The Funambulist

The Funambulist Magazine Issues. Image via The Funambulist

Across these examples, one theme is clear: writing is not “just” talking about architecture; it is a mode of doing architecture; it’s not commentary, it is a form of architectural labor. It creates conceptual space, curates critical reflection, educates future architects, and agitates for political change. As ArchDaily collaborator Guy Horton observed, “writing mediates architecture the way it mediates life”. Rather than a mere support act, writing can make things happen in architecture by coaxing new meaning and situating designs in deeper contexts. In practice, this means good architectural writing can be generative and transformative; it opens up dialogues beyond the drafting table, engaging broader publics and diverse disciplines in what architecture might become.

The Architect as Editor

If writing is an architectural act, then editing and publishing are its extended tools. The processes of curating content, shaping publications, and disseminating ideas — whether in books, magazines, or digital platforms — have long influenced how architecture is discussed, theorized, and projected. One can trace a lineage from Renaissance printer-patrons who published Alberti’s treatises, to the editors of early 20th-century manifestos, to the curators of today’s hybrid forums. In every case, the medium has shaped the message of architecture.

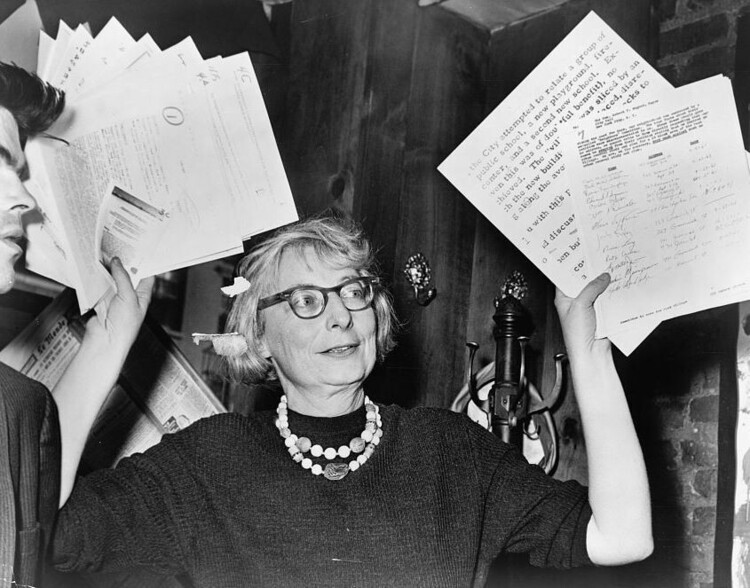

Jane Jacobs. Image via Wikipedia under Public Domain

Jane Jacobs. Image via Wikipedia under Public Domain

The rise of architectural journals and criticism in the 19th and 20th centuries helped architecture reach wider publics and enter broader cultural debates. These platforms carried the arguments of modernists, brutalists, and postmodernists, effectively shaping the field by deciding which voices and visions gained visibility. Architects themselves often took on the editor’s pen: Le Corbusier co-founded L’Esprit Nouveau to advance modernist ideas; Peter Cook launched Archigram as a speculative magazine-manifesto; and figures like Bruno Zevi or Charles Jencks authored editorial frameworks that influenced generations.

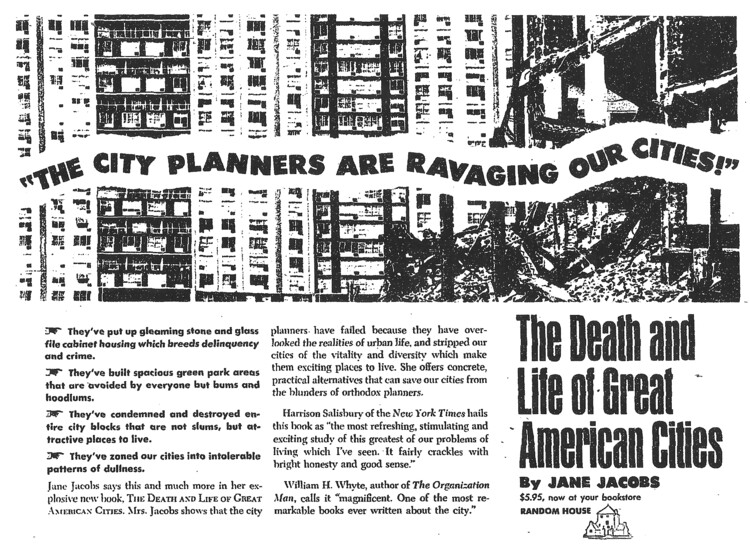

As architectural journals and publications grew in the 20th century, a powerful field of public architectural criticism emerged, pioneered by influential women. For figures like Esther McCoy, who was trained as an architect, and Ada Louise Huxtable, an architectural historian, writing became a vital form of practice at a time when conventional career paths for women in architecture were severely restricted. Through her books and articles, McCoy was instrumental in introducing California Modernism to a global audience. Huxtable, writing for The New York Times, legitimized architectural criticism for a mass audience and became the first critic to win a Pulitzer Prize for her work. A powerful contemporary, Jane Jacobs, though not an architect, radically reshaped urban thinking with The Death and Life of Great American Cities, giving communities a voice to resist detrimental top-down development. Together, their work demonstrated the active power of words to shape public discourse and the built environment, a legacy of accessible and civic-minded criticism that continues today in the work of writers like Alexandra Lange.

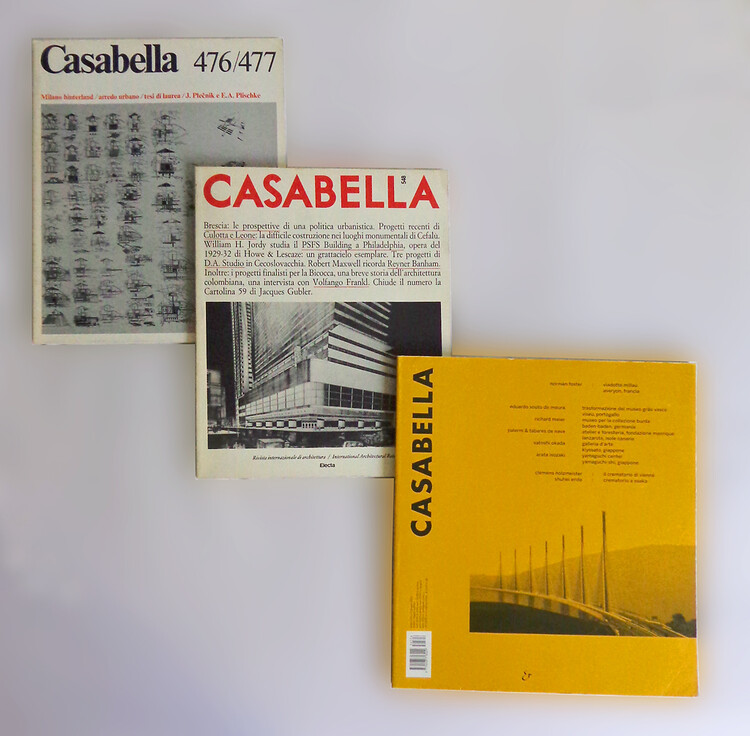

In contemporary practice, editorial work in architecture is developed across multiple forms. Platforms like e-flux Architecture, KoozArch, and Real Review operate at the intersection of publishing, research, and design experimentation. Others, such as Log or Arquitectura Viva, maintain consistent editorial voices that bridge academia and the profession. These platforms shape architectural discourse not only through what they publish, but through how they curate, contextualize, and circulate ideas. Alongside them, certain individuals have helped define the field of architectural criticism. Figures such as Paul Goldberger, Blair Kamin, and Michael Kimmelman brought architectural debate into the public sphere, engaging broad audiences with clarity and depth. Rather than addressing architects alone, their writing transformed architecture into a matter of civic and cultural relevance — showing that the critic, like the editor, participates in the construction of the discipline through language.

Casabella. Image via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 3.0

Casabella. Image via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 3.0

What these editorial practices reveal is that the architectural publication has become a flexible, hybrid medium, that the discipline now circulates not only through journals or institutions but through decentralized, self-initiated infrastructures of knowledge. But what remains constant is the core ambition: to articulate a position, to construct a shared conversation, and to influence architectural culture. Whether through an exhibition catalog or a critical essay, editing is a spatial practice. As architecture continues to evolve beyond buildings, the figure of the architect-editor plays a central role in imagining what the discipline can become.

The Challenge and Responsibility

Writing about architecture means translating visual/spatial experiences into linear text, which is no simple task. Some architects favor accessible, direct language; others lean into rhetorical experimentation. Both approaches reveal that writing is not just a method of explanation, but a tool of projection, criticism, and imagination. Good writing demands the same rigor as good design; it must balance precision with creativity.

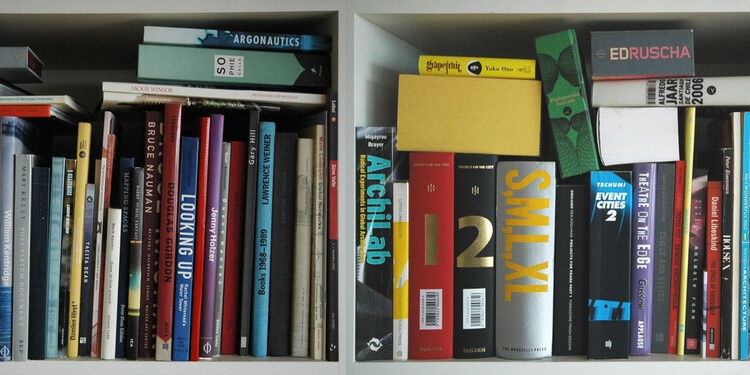

Dillier Scofidio’s library. Image © Carlos Solis

Dillier Scofidio’s library. Image © Carlos Solis

At the same time, overly simplistic writing can flatten the richness of architecture. A building is never just a function or material; it embodies atmosphere, context, and culture. Some of the most influential architectural writing has been visionary rather than straightforward. Manifestos, by nature, thrive on passionate, sometimes opaque rhetoric that sparks imagination rather than spelling everything out. The key is that the writing serves a purpose beyond mere description: it challenges or inspires. As Guy Horton argues, “writing about architecture needs to be conceived as something much greater than a mere facilitator of architectural practice”. In other words, good writing is first and foremost capable of moving people; it should reach “beyond the confines of institutionalized insularity” and out to the “popular imagination”.

In this evolving landscape, online platforms play a unique role. By circulating ideas daily across languages and geographies, they accelerate the rhythm of architectural discourse. This immediacy brings opportunities and risks: the possibility of broader engagement, but also the challenge of sustaining depth, rigor, and editorial discernment in a context shaped by volume and speed. Still, these platforms serve as important arenas where architecture is not only shown but discussed, questioned, and reframed. They host a crucial part of the discipline’s intellectual life, one that happens not in the silence of drawings or the permanence of buildings, but in the openness of language. To write is to participate in the shaping of architecture’s present and its possible futures.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Architecture Without Limits: Interdisciplinarity and New Synergies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Cover of recent reprint of Vers One Architecture (1995; from second edition of 1928). . Image via Common Edge

Cover of recent reprint of Vers One Architecture (1995; from second edition of 1928). . Image via Common Edge New-New York, 1969. This drawing was displayed as part of the exhibition “Drawing Ambience- Alvin Boyarsky and the Architectural Association” © Superstudio. Image © Collection of the Alvin Boyarsky Archive

New-New York, 1969. This drawing was displayed as part of the exhibition “Drawing Ambience- Alvin Boyarsky and the Architectural Association” © Superstudio. Image © Collection of the Alvin Boyarsky Archive Extrastatecraft- The Power of Infrastructure Space by Keller Easterling . Image Courtesy of Verso Books

Extrastatecraft- The Power of Infrastructure Space by Keller Easterling . Image Courtesy of Verso Books Ada Louise Huxtable photographed in her home, 1976. Image © Lynn Gilbert, via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 4.0

Ada Louise Huxtable photographed in her home, 1976. Image © Lynn Gilbert, via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 4.0 In honor of the 50th anniversary of The Death and Life of Great American Cities. 1961 Random House advertisement for the book.. Image © pdxcityscape, via Flickr under CC BY 2.0

In honor of the 50th anniversary of The Death and Life of Great American Cities. 1961 Random House advertisement for the book.. Image © pdxcityscape, via Flickr under CC BY 2.0 ECHO* is the first publication from the research-driven ecosystem, ECHO, by Portuguese architecture office MASSLAB.. Image © MASSLAB / ECHO

ECHO* is the first publication from the research-driven ecosystem, ECHO, by Portuguese architecture office MASSLAB.. Image © MASSLAB / ECHO