Last Sunday, Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves met at 10 Downing Street to finalise plans for their long-anticipated government “reset”. Throughout the summer, they had discussed how Starmer could revive his struggling project, as some aides still describe it.

One key idea was the appointment of the prime minister’s own chief economic adviser. Starmer was entering what he calls the defining “second phase” of his premiership, aiming to project optimism and a renewed sense of purpose. He was aware he had lost the trust of many of his MPs following a series of mishandled U-turns, Labour’s sharp decline in the polls and his own dismal personal approval ratings.

But within 48 hours, the PM was facing a crisis over Angela Rayner’s tax affairs. After a week of mounting speculation, she released a personal statement on Wednesday admitting that she had underpaid £40,000 in stamp duty on an £800,000 seaside flat she had recently purchased in Hove, East Sussex. She expressed deep regret and referred herself to the prime minister’s independent ethics adviser, Sir Laurie Magnus.

Angela Rayner arriving at Downing Street for the first Cabinet meeting after the summer recess last week

KARL BLACK/ALAMY LIVE NEWS

Despite claims from her supporters that she was being unfairly targeted by the “right-wing press”, it emerged that the deputy prime minister — and housing secretary, no less — had indeed failed to pay the additional stamp duty owed. She attributed the error to incorrect legal advice that, she said, had not “properly taken account” of her circumstances. A spokesman for one of the firms involved denied that, saying they had been “made scapegoats”.

Labour’s “Red Queen” was in serious trouble. While in opposition, she relished denouncing Tory opponents like Jeremy Hunt and Nadhim Zahawi for alleged financial misconduct. Now she was being accused of hypocrisy. What goes around comes around.

• Angela Rayner’s complicated life and how she fatally damaged her brand

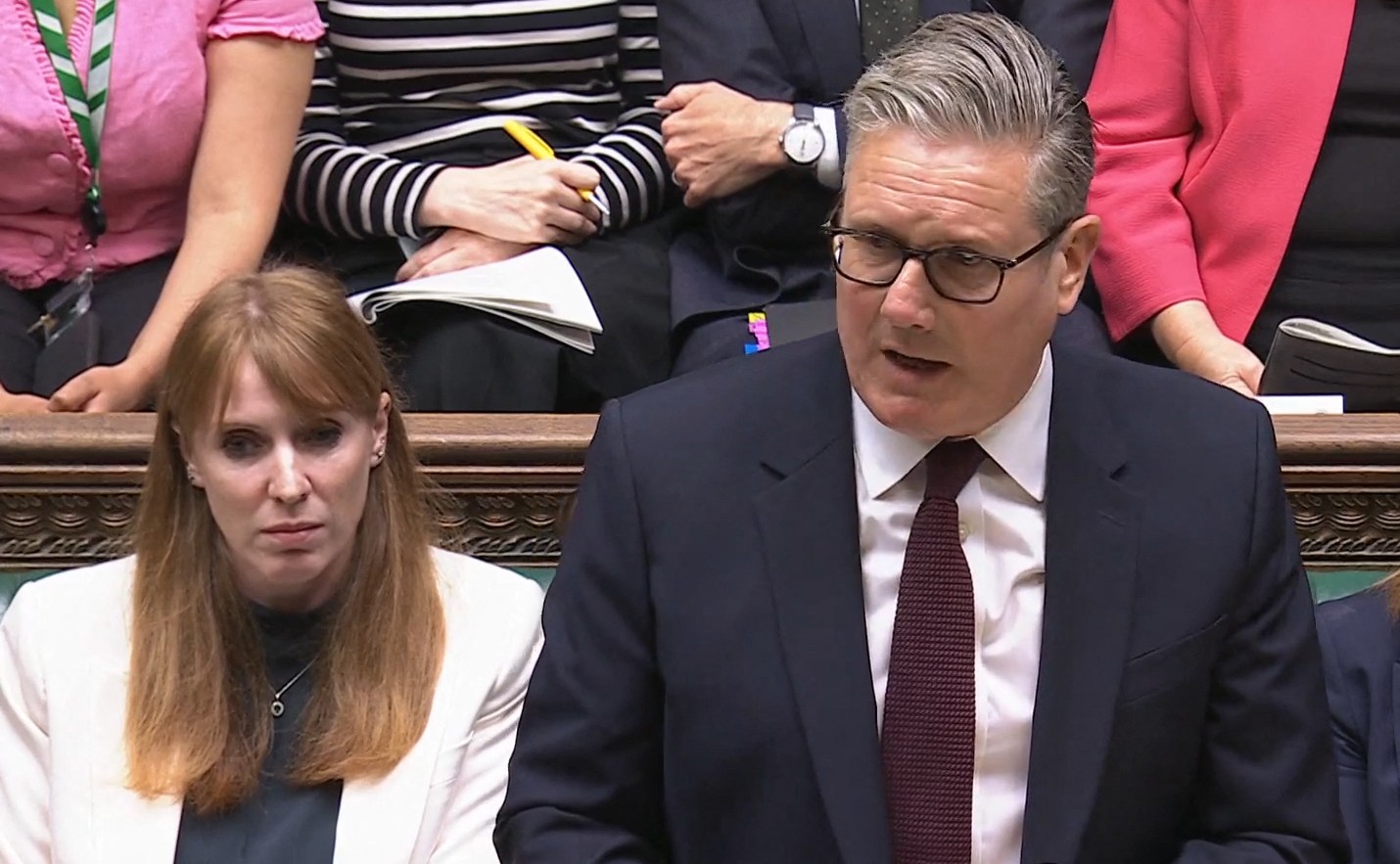

At prime minister’s questions on Wednesday Rayner sat next to Starmer, who defended her robustly, citing her “working-class woman” credentials as if her social background conferred some kind of special status. On his other side was Reeves, the chancellor. Here were the two most powerful women in government and, for different reasons, they both seemed utterly miserable, reflecting the wider mood of unhappiness on the Labour benches.

Sir Keir Starmer and Rayner at prime minister’s questions

PRU/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Rayner was expected by some colleagues to resign on Wednesday. She did not, and Starmer did not want her to. But then on Friday, Sir Laurie concluded that she had breached the ministerial code because she had ignored advice to apply for expert tax help on the purchase of her flat. It was over. She resigned as both deputy prime minister and, most significantly, as the elected deputy leader of the party.

An already difficult week for Starmer was getting worse. He had been forced into an emergency cabinet reshuffle and now faced a deputy leadership contest, too — one likely to expose all Labour’s internal divisions unless a unity candidate emerges. One possibility is Shabana Mahmood, the newly-promoted home secretary and one of Starmer’s most capable senior ministers.

The feeling among backbenchers is just as despondent. “I’ve never known the mood to be so openly seditious,” one influential MP told me, adding: “Keir has no authority in the PLP [parliamentary Labour Party]. But the PLP has never removed a sitting Labour leader. We have this bizarre gap between the analysis of the problem — ultimately it starts at the top — and a willingness to act.”

• Inside Labour reshuffle: how a moment of sadness turned into a frenzy

As the party’s elected deputy leader, Rayner commanded her own power base, which is why it was politically expedient for Starmer to keep her inside the cabinet. She was popular with members and also served a strategic purpose: her presence subtly reinforced the message — if I go, she is next in line.

Rayner had built an infrastructure of support among the trade unions that enabled her rise and has been adept at courting all factions of the parliamentary party, along with wealthy donors. “Unlike Starmer, she knows how to build relationships,” one longtime donor told me.

Rayner is out but not finished. Freed from the constraints of collective responsibility, she will now be able to manoeuvre and machinate more freely, which means Starmer will need a “Rayner strategy” to deal with her inevitable interventions.

Labour MPs are openly speculating not only about who the next elected deputy leader will be but who might replace Rayner as the next leader-in-waiting and, therefore, prime minister, should Starmer goes before the end of this parliament. Mahmood, Wes Streeting, the health secretary, and Andy Burnham, mayor of Greater Manchester, are the three leading names.

Andy Burnham

SUNDAY TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER JACK HILL

Since standing down as an MP, Burnham has reinvented himself as the self-styled king of the north. He is liked by the soft left, who want higher taxation and a more left-wing vibe, and has evolved a more direct, populist style — plain speaking, a bit cocky. He is a political version of the fast-talking footballer-turned-entrepreneur Gary Neville; they are friends. He and Starmer have clashed before, although recently they have reached a more pragmatic working relationship.

The vision problem

Starmer is always being asked what his vision is, but, as an unsigned paper on strategy called What Did we Learn on our Summer Holidays?, which has been circulating among MPs and aides, bluntly puts it: “Keir Starmer has no vision and he will never have one. The government has no purpose and the cabinet is not capable of defining it.”

Its author told me: “This government is not a tragedy, it’s a farce. There’s no dignity in the project, no moral stature.”

These harsh words reflect the exasperation of those who have been working assiduously behind the scenes to provide the government with an intellectual framework and something approaching a public philosophy. Is Starmer even listening?

Despite being in opposition for 14 years, Labour came to power spectacularly ill-prepared. The hard work of stress-testing policy, of developing a theory of government, had not been done. Sue Gray, Starmer’s first pick as chief of staff, is blamed for the mess; the reality is that it was a collective failure a decade in the making.

What is Labour’s equivalent of Stepping Stones, the wide-ranging 1977 policy report co-written by John Hoskyns, the businessman who later became head of Margaret Thatcher’s policy unit?

Stepping Stones provided an overarching analysis of British economic decline, an intellectual framework for radical reform and for what would become Thatcherism — the weakening of trade union power, deregulation, privatisation, tax cuts and tight monetary policy to combat inflation. Hoskyns and other free-market ideologues told Thatcher that if she was to transform Britain, she would have to break taboos and think the unthinkable.

When you speak to Starmer’s aides and the heads of left-leaning think tanks, they use similar language about structural decline and the failure of state capacity. But when you ask what Starmer is prepared to do about it, they don’t know — and they’re meant to be providing the ideas and intellectual ballast.

The appointments made as part of the internal reshuffle of No 10 on Monday confused many. Tim Allan, the veteran Blairite and PR magnate, came in as head of communications (the third in less than 12 months); Minouche Shafik, a seasoned academic and bureaucrat (but with no experience of running a business or creating wealth), was appointed chief economic adviser; and Darren Jones became chief secretary to the prime minister.

Darren Jones

VICKI COUCHMAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

Jones previously served as chief secretary to the Treasury and led the inter-departmental negotiations on the spending review. He carries himself with the confidence of a newly appointed head boy, high on the thin air of his own self-importance. He is, however, capable with spreadsheets, and has been tasked with improving delivery across departments. In Friday’s second reshuffle he was garlanded with another additional title, chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

I was told the internal No 10 reset was more about “competence and delivery” than political strategy. But this seems like the wrong way round: in government you first need a political programme, then you find the people to implement it.

‘Do something queasy’

One senior cabinet minister says the party will need “to do something queasy” on immigration to win the trust of voters. But why restrict this to immigration? What about welfare and the sclerotic administrative state?

Labour politicians are too complacent in their belief systems. It’s time they started thinking against themselves in the way that progressives, both left and right, have done in Sweden and Denmark in response to mass public disaffection about open borders and societal fragmentation.

And what of the Reeves-Starmer relationship at the end of this traumatic week for Labour? There’s no doubt that they, plus Morgan McSweeney, the prime minister’s chief of staff — strengthened by the reshuffle thanks to the empowerment of allies such as Mahmood (from the Blue Labour right) and Pat McFadden (from the Blairite right) — remain the three most significant figures in the government.

Rachel Reeves has played down suggestions of a rift between her and Starmer

REUTERS/TOBY MELVILLE/FILE PHOTO

Reeves backed the appointment of Shafik (although she was ultimately Starmer’s choice) and championed the promotion of Jones. Her aides are adamant that there is no rift between the chancellor and the prime minister. They welcome more creative tension and more heterodox thinking on economic policy but don’t want outright conflict, as there was during the New Labour years, when Gordon Brown exerted a mesmeric hold over the Treasury and even Tony Blair submitted to his will.

They believe that, paradoxically, rising long-term borrowing costs will strengthen the chancellor’s argument about the need for fiscal discipline and greater control over public spending. And she will resist the pressure from MPs to lift the two-child benefit cap, a totemic campaign for the soft left.

But together Starmer and Reeves are bound on a wheel of fire: they accept that the budget on November 26, in which taxes will rise again, will in large part determine their fate.

The looming shadow

This has been a terrible week for Starmer after a dismal first year in office. It has exposed the core weaknesses of his leadership: a lack of political instinct and any coherent political philosophy, a reactive rather than proactive approach (note the asylum crisis), and a tendency to manage the status quo rather than lead and pursue serious reform.

Perhaps Rayner’s fall — and the sweeping reshuffle it provoked — will, in retrospect, mark the moment Starmer finally changed direction and grasped the full scale of the problems facing the country in this new political era. Or perhaps not.

If the prime minister fails to set a clear direction for his government in his conference speech, and demonstrate it by clearly defined intentions and actions, Labour will be routed in next year’s Scottish, Welsh and English local elections.

Looming over this faltering government is the shadow of Nigel Farage’s Reform. Labour do not consider the Conservatives to be a serious electoral threat — “They scarcely have a pulse now,” one senior aide said — but Reform are viewed differently.

Farage at the Reform UK party conference

SUNDAY TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER JACK HILL

“Reform can’t govern without the north,” one red-wall MP said. “Who can keep it? It takes us to difficult decisions about the leadership.”

Call it sedition, or simply an expression of realism about the state of Starmer’s premiership — and how and why an increasing number of his own MPs believe it might end.