Joanne Woodhouse and Henry Godwin live at opposite ends of England and used to sit on opposite sides of the political fence – until both decamped to Nigel Farage’s Reform UK party.

The far-right party held its annual conference on Sunday, where it celebrated its surging popularity.

Before decamping to Reform, Woodhouse was a one-time voter for the UK’s centre-left Labour Party in the north-west of England. Godwin, formerly a conservative based near London.

The middle-aged pair appeared typical examples of anti-immigration Reform’s ability to draw disaffected voters from both left and right, as it builds on an unprecedented performance in local elections in May.

“I want to see a big change,” Woodhouse, an independent locally elected official in Merseyside who joined Reform two months ago, said at the two-day event in Birmingham, central England.

The 57-year-old voted for Brexit in 2016 because she “wanted our borders to be closed” and backs Reform “to protect our community, our traditions”.

“I’m totally disappointed by Labour — disappointed by everything they are doing. People are struggling.”

Godwin, 52, a free speech advocate most concerned by perceived curbs on freedom of expression, signed up for Reform after Labour won power 14 months ago, following 14 years of Conservative rule.

“The Tories in my mind have completely lost their way… they’ve lost their conservativeness,” he said.

“So, as far as I’m concerned, there’s only one party to vote for, and that’s Reform.”

‘Vast disillusionment’

Reform’s growing appeal mirrors advances by far-right parties across Europe and US President Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” movement in the United States, but at breakneck speed.

Reform won 14% of the vote in the 2024 general election, netting it five MPs under Britain’s first-past-the-post election system, which has long suited the two established parties.

It has since trebled its membership to over 240,000, seized control of 12 local authorities across England in May and led in all national polls over recent months.

Late-August fieldwork by conservative pollster James Johnson unveiled at Reform’s conference showed it on 32% support, 10 points ahead of Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s Labour.

The surveys indicated immigration and patriotism were key to its appeal, with almost half of supporters classed as “pessimist patriots” – typically older, non-graduates who backed Brexit and oppose climate change mitigation policies.

They were uniformly downbeat about the country’s trajectory.

Crucially, there are plenty more such voters still unclaimed by Reform ahead of the next election, according to Johnson, which is not due until 2029.

“It’s very rare in politics to have… voters that you need to win looking a bit like your existing base – that’s a great place to be,” he said.

“They’re flocking to Reform because they basically feel they have no other option,” he added, citing “vast disillusionment” and “vast lack of trust” in the long-established parties.

While acknowledging “four years of being a frontrunner is tough,” Johnson could see Reform attaining a 35% share of the vote at the next election.

“If they’re in a two-party system, that wouldn’t be enough. But they’re in a fractured system, and that will get them a stonking majority.”

‘Hope’

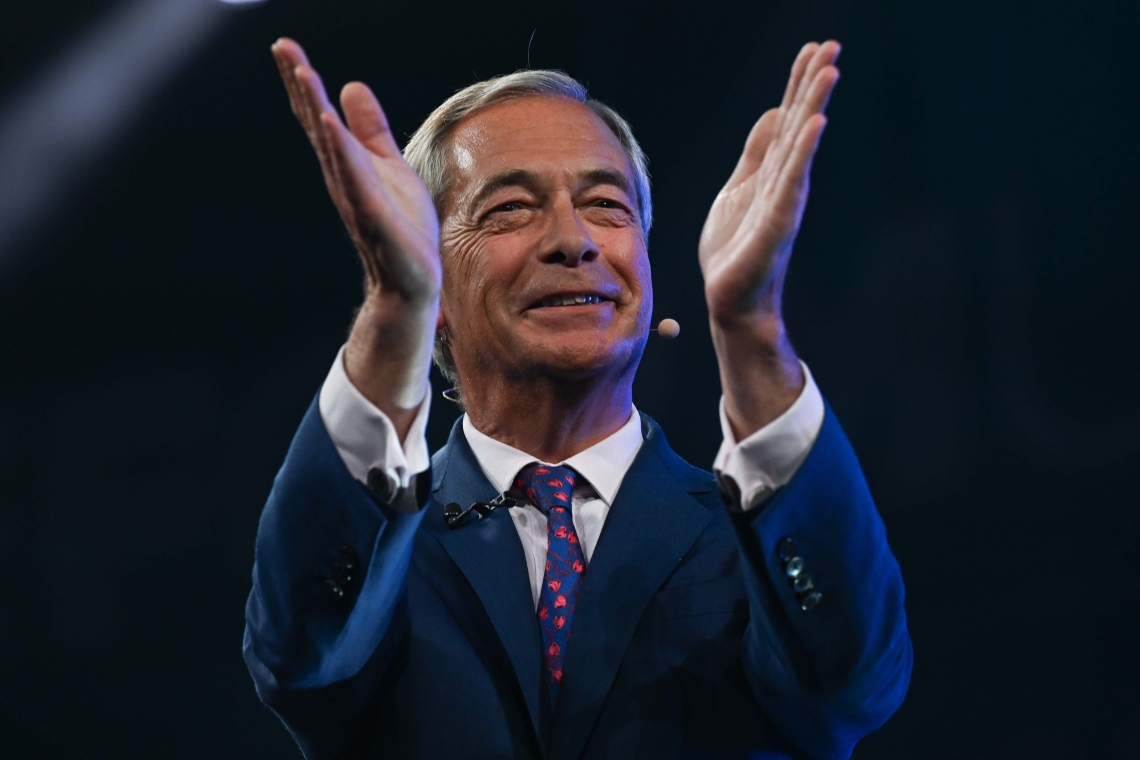

For many Reform converts, the appeal of ever-present Eurosceptic Farage, a long-time ally of Trump, appeared as important as key policy issues like immigration.

Amelia Randall, a Reform councillor in Kent, southeast England, where the party won control four months ago, believed Farage had “a very good chance to be the next prime minister”.

“The spirit is rising a lot inside the party,” she said as its leader addressed the conference Friday.

Like Johnson’s research, new polling by More in Common found the party’s base was becoming increasingly mainstream, with the number of female Reform supporters fast catching up with men.

“He’s giving us hope,” retiree Karen Dixon said of Farage.

She became a party member nine months ago after growing up in a Labour-voting family and later siding with the Conservatives.

“I didn’t want to vote anymore,” she said.

Some younger voters also appeared attracted by Reform, though not yet in the numbers Labour typically draws, according to pollsters.

“He definitely shows leadership, that’s what I’m getting,” student Marcus Ware said after becoming a “young member” and turning up to hear Farage speak.

“I don’t see why young people can’t be interested in this.”

He said he liked Reform’s low-tax message, though noted concerns that its tax-and-spend numbers at the last election did not “add up”.

He dismissed criticism that the party’s hard-right agenda was divisive.

“The label of being divisive and too extreme is very subjective,” he said.

(cp)