The mansion has remained unfinished for decades (Image: Eddie Mitchell)

Nichloas van Hoogstraten is perched on a windowsill in the reception of the modest hotel he owns in East Hove, Sussex. As we shake hands, I can tell he is distracted, irritated by a memory the heavily-pruned trees outside have stirred.

The bare trunks lining the back fence are the result of an employee trimming the branches a little too enthusiastically; which clearly annoyed Hoogstraten, who planted them to give hotel guests privacy. “He was sacked on the spot,” he says grimly, taking a seat opposite a pool table. It’s impossible to tell if he’s joking, but I suspect not.

At a glance, it would be tough to tell the 80-year-old is a man of immense wealth. Back in his 80s heyday, he was rarely seen out of a double-breasted suit. Today, he’s dressed in a grey Karate Dojo gym T-shirt, trousers, and trainers.

At the height of his fame – or should that be infamy? – Hoogstraten was known as “Britain’s most feared landlord”.

Born into humble origins in Sussex, Hoogstraten started a property business on the profits earned from selling his childhood stamp collection. By his early 20s, he’d built an empire across the South Coast and gained a reputation for being a ruthless operator who acquired homes from anyone who was unable to pay back his high-interest loans.

The mansion has an estimated value of £100m – when finished (Image: Eddie Mitchell)

So when he stares at me with a steely expression and says he hasn’t dealt with the press in three decades, I get a sense of why people were intimidated.

“I used to have a bucket of s*** and p*** by the front desk for throwing,” Hoogstraten continues. “That Bashir guy came unstuck when he came up here,” he says, referring to BBC journalist Martin Bashir. “He nearly got thrown off the scaffolding. The things we agreed that we wouldn’t discuss, he asked about.”

I’ve been spared a dousing in excrement because Hoogstraten and his son Max want to set the record straight about one story that continues to generate huge public attention – the mystery of the family’s vast, unfinished mansion, Hamilton Palace.

Started in 1985, the grand neo-classical estate set across 100 acres of rolling Sussex countryside was designed as a throwback to a bygone era of Georgian opulence, complete with Romanesque columns and brass domes.

Had it been finished, the stately home would probably not have generated much interest, even though it would have been bigger than Buckingham Palace.

But the abrupt halting of work in the late 90s, just as it appeared to be nearing completion, has created a sense of mystery that has spawned hundreds, if not thousands, of articles and videos in the subsequent quarter of a century.

They rarely contain any new updates about the project; most tend to recycle old material about Hoogstraten’s colourful life, including his criminal convictions, murder trial, and relationship with the late Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe, whom he befriended as a consequence of his huge land holdings in the country.

But over the course of nearly two hours, Hoogstraten and Max break their three-decade silence to explain the exact reasons why work stopped and what the future holds for the palace. Part of the reason articles on Hamilton Palace keep doing the rounds is nothing to do with the building; it’s the man. Often, with the ultra-wealthy, there is a limit to what we journalists can know or say. But with Hoogstraten, anyone writing an article has a wealth of salacious publicly available information to draw from.

It’s quite easy to patch together an engaging story that quotes a judge referring to him as a “self-imagined devil” or the man himself telling the BBC: “I’m probably ruthless and I’m probably violent.” The upshot is that Hoogstraten, who, throughout our conversation, makes it plain he is extremely distrustful of technology, is an online sensation.

“[One of my tenants] told me every time my name appears on one of those computer things, it goes ‘boom’,” he says, gesturing to my phone.

“He wanted me to start a social media account and told me I could earn ten grand a month. Why would I want to do that for ten grand?”

If the endless stream of articles only sparked the occasional email from a friend, perhaps it could be ignored. These days, it tends to be his son, Max Hamilton, 40, who deals with issues relating to the Palace. His soft voice and round features contrast with his dad’s sharp tone and angular cheekbones. He explains to me, in a thoroughly polite manner, that the coverage is inviting intruders.

“The thing that annoys us is the amount of people we have trespassing and the excuse is always ‘we’ve read it’s abandoned’,” he says. “But this is an estate that has staff, 24-hour security and things happening every single day.”

The palace is surrounded by beautiful countryside (Image: Eddie Mitchell )

He says anyone who does make it onto the grounds would be in little doubt that this is a place they shouldn’t be. The gardens are maintained, there are hunts on the land, people live there and there are clear signs adorning the perimeter fence stating this is private property.

Those who make it closer to the building tend to have worse intentions, Max says. Thieves have targeted the unfinished building numerous times and the family regularly has to contact the police.

“It’s dangerous,” he adds. “These people are taking dangerous risks, and someone will eventually get hurt. It doesn’t help that the trespassing laws are nearly non-existent and the criminal damage [penalties] are weak.”

Despite the fact that there are no ongoing building works or immediate plans, both Hoogstraten and his son maintain with utter conviction that the project will eventually be finished. There might be foliage snaking its way around the scaffolding but, in their eyes, renovations have only paused.

Max can’t give a timeframe for when that might happen because “it’s not on the agenda”.

He adds: “We’ve just got so many smaller everyday things [occupying us]. My dad has every intention to finish it, but he still works 16 hours a day every single day.”

Given the quarter-century hiatus, I asked whether they’d ever considered selling the property. An estate agent told me ahead of the meeting that it could fetch as much as £100 million if sold. But the Hoogstratens just look bemused at the idea that they might be persuaded to sell up.

“We’ve had all sorts of people trying to buy it,” Hoogstraten reveals, “people with mega money.”

So why did building work stop? “Remind me,” says Hoogstraten to Max in a rare moment of uncertainty. The distractions that led Hoogstraten to cease work might be complex and stretch back 40 years, but one thing is clear, he insists, the builders were told to down their tools after a series of mistakes.

“There were major issues,” Max explains, “not just in terms of aesthetics but also in terms of [what it would take to] rectify [them].”

Hoogstraten remembers being infuriated by the positioning of a column that ruined one of the key features: an unobstructed view from one side of the building to the other. On reflection, he blames the architect, even though he also says: “I designed every last bit of that building, [the architect] just did the paperwork.”

In addition to the offending pillar, the mansion’s owner recalls being irritated when he saw that the servants’ staircases were tight and winding. This, he pointed out, was no good for staff carrying heavy trays.

The reason these mistakes became unmovable obstacles was because of the moment in Hoogstraten’s life when they took place. He was charged with murder and then distracted by the situation in Zimbabwe, where he has vast land holdings.

“A number of things came together,” Max explains, “And it was a project you needed to be on-site every day for. My dad’s attention was on investments in Zim.”

When he walked into the Old Bailey dock in 2002, charged with murder, Hoogstraten was no stranger to either a prison cell or the courtroom.

In trouble with the authorities since he was a boy, his conviction in the late 1960s, aged 22, for paying a gang to throw a grenade into a Brighton business associate’s house over an unpaid debt, sparked a media obsession.

Described in the papers at the time as Britain’s ‘self-styled youngest millionaire’, the combination of wealth and criminality has remained an irresistible story ever since.

Before we met, I wondered how willing he’d be to discuss his past convictions, so I was surprised when he brought up the most damaging allegations himself.

Hoogstraten tells me the grenade story is all “bullshit” – “so what happened?” I ask, tentatively.

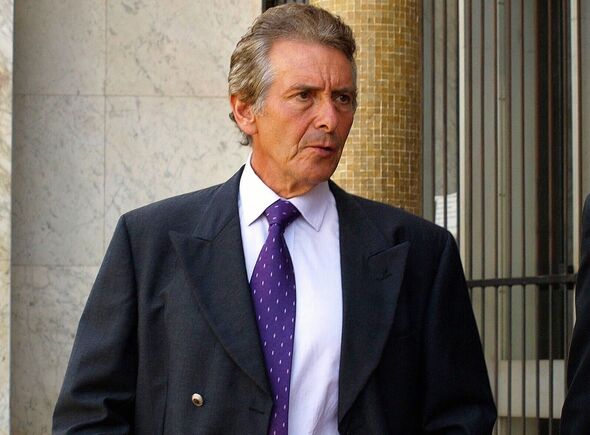

Nicholas van Hoogstraten has had a colourful past (Image: Getty)

“Some gangsters in London in the scrap metal business,” he pauses. “Well, I call them gangsters, but they were really decent people. They used to come down here to Hove regularly. They wanted to try and impress me and, on the basis they were doing me a favour, lobbed a hand grenade into [a man who owed me money’s] house.”

He scoffs: “Imagine throwing a hand grenade into someone’s house for £3,000.”

He then adds: “All they had to do was grab the guy and chop his bollocks off, or, like we do today, chop his hand off.”

His son Max interjects: “That was a joke.”

“No, it wasn’t.” Van Hoogstraten snaps back.

The murder case is also branded ‘bull***.’

Initially found guilty of manslaughter, Hoogtraten was cleared on appeal, but feels his notorious reputation was present in the courtroom.

“Everyone knew already that I was stinking rich and was in bed with Mugabe,” he says.

When Max suggests his father’s life changed in the wake of the murder trial, Hoogstraten is dismissive. “The bigger picture was always Zimbabwe,” he interjects.

Hoogstraten’s relationship with the country began when he was a teenager. He bought land in what was then Rhodesia from an estate without seeing it. When he finally visited some years later, he “fell in love” with the place.

It’s fair to say it’s been a controversial relationship. His massive land ownership and friendship with Robert Mugabe have often been criticised.

“I’m seen as this white man who’s owned more of Zimbabwe than anyone else,” he tells me.

This, he claims, is an unfair characterisation of his interests. “I am responsible for thousands of people,” he says, “They are living on my land and working for my companies.”

The family says these ‘responsibilities’ include healthcare and education, “we even give them hampers,” adds Van Hoogstraten. “I did something that nobody has done since the white farmers left and that’s providing everything for the black people.”

He makes no secret of his relationship with the country’s infamous tyrant.

“I used to deal with him on a personal basis,” he says, “He used to clear everyone out of the room and say, ‘Nick, tell me the truth.’”

Hoograstaten has always maintained a positive view of Mugabe and adds with fierce conviction the Zimbabwean president “wasn’t involved in any corruption”.

But it was Mugabe’s controversial land reform programme, set up to redistribute white-owned land to black Zimbabweans, that started causing havoc at the time Hamilton Palace was paused.

The violent and sometimes deadly eviction of white farmers made headlines around the world. Hoogstraten’s lands were occupied, but never lost to the same extent as others and still spends lots of his time in the country.

The property isn’t abandoned, father and son are at pains to point out (Image: Eddie Mitchell )

So much time has passed it’s hard to know conclusively if it was the chaotic land seizures of white landowners in Zimbabwe or being accused of a terrible crime that took his focus from the Palace.

Yet leaving such an expensive project on pause for so long is curious for a man who examines everything’s value – he has a Co-op loyalty card to ensure he gets the best deals at his local discount supermarket and was famous for reusing teabags.

It is difficult to assess Hoogstraten’s exact fortune.

Today his vast property empire and art collection have been valued at sums that would comfortably make him a billionaire.

He dismisses figures like Elon Musk, whose value lies in share options, or Donald Trump, “who has everything mortgaged up to the eyeballs,” as not being properly rich.

“People who have mortgages are just bullshitters,” he adds.

In his opinion, the homes of the ultra wealthy these days are filled with expensive items that don’t hold any lasting value and “you’d be hard pushed to find any Louis XIV furniture anymore.”

As I hear Hoogstraten talk wistfully about the days of ‘real money’ when lords and ladies owned large swathes of Africa, I begin to understand why Hamilton Palace remains so important to him.

This was his great homage to the vision wealth he no longer believes exists, although he tells me “the world is f**ked” and we’re “on the way to Armageddon,” even with everything in ruins, there are few greater legacies than a palace you built for yourself.

When Max asks if there is any other example of a private individual building that’s a project like the palace, he’s quick to fire back.

“No,” replies Hoogstraten, “because nobody has any real money anymore.”

The palace should be spectacular when finished (Image: Eddie Mitchell)