The gentle hiss of boiling water. The rhythmic ticking of a kitchen clock. These were the mundane sounds of a quiet afternoon at home for mother-of-two Natalie Ive.

But on this particular day, in 2018, the familiar morphed into the terrifying.

Having placed eggs on the stove to boil for lunch, she found herself paralysed, the world around her dissolving into an incomprehensible blur.

‘I remember putting the eggs on and not much else. I’ve had to rely on family to fill in the missing pieces,’ Natalie, now 53, recounts.

The boiling water on the hob seemed uncanny. What was it doing?

She could see her front door but suddenly didn’t know how to grasp and turn the handle to open it.

Her phone, resting on the bench, was a familiar object rendered utterly useless. She knew it was hers, but couldn’t think how to unlock it.

When her daughters called, expecting their mother to answer, they couldn’t reach her. Their concern prompted a call to a family friend, who arrived to find the front door mercifully unlocked.

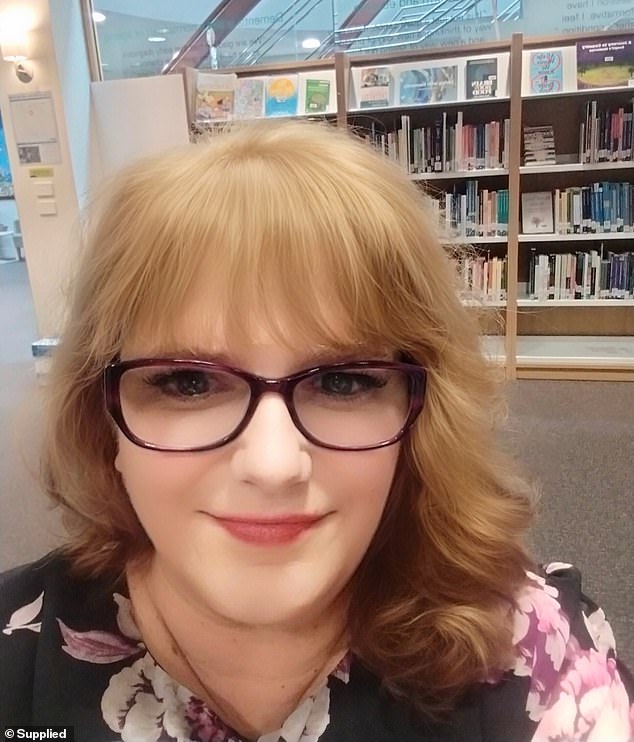

Natalie Ive (pictured) was diagnosed with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) in 2021 at age 48

‘I couldn’t speak and didn’t know their names. I couldn’t tell them anything. I didn’t know where medications were. They had to look for it themselves,’ Natalie recalls.

An ambulance was called. Paramedics initially suspected a stroke, rushing her to hospital where days of observational tests yielded no answers.

This profoundly unsettling incident was not Natalie’s first experience of sudden, frightening forgetfulness.

Just months prior, at 45, while working as a dedicated special education teacher in Melbourne, she had experienced a similar, moment of cognitive disconnection.

One morning, immersed in reports and emails, her fingers simply froze above the keyboard.

‘I was just starting at the screen blankly. I didn’t know what to do. I thought, ‘What is going on here?’ Natalie recounts.

‘I was scared and did a process of elimination, like a checklist, making sure I wasn’t stressed or anything. I wasn’t.’

She brushed it off, yet these alarming instances persisted. Her ability to articulate her thoughts was gradually eroding.

In 2018, Natalie (pictured with her two daughters) noticed she was struggling to communicate

Natalie, who used to help her adult daughters with their school assignments, now found herself seeking their guidance on basic vocabulary.

‘I would cry alone when my daughters were out of the house because I didn’t want them to worry or think anything was wrong,’ she admits.

Yet, this was merely the prelude to a far more formidable challenge.

Natalie, always a perfectionist, began to forget small but important pieces of information. Sometimes, she simply could not find the word to communicate what she was thinking.

‘I would walk through the shopping centre then I would all of a sudden forget why I’m there, what I was doing or what the shopping centre was,’ says Natalie, who is now a lecturer and researcher at the University of Tasmania.

These ‘flickering’ moments left her disoriented. Eventually, she would remember what she was supposed to be doing – but the feeling of being in the middle of a public place and not knowing why she was there was bewildering, to say the least.

‘I haven’t changed as a person. But what has changed is just the communication part of my brain,’ she says

What is Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA)?

Primary progressive aphasia is a type of frontotemporal dementia.

Primary progressive aphasia is a rare nervous system condition that affects a person’s ability to communicate.

People who have primary progressive aphasia can have trouble expressing their thoughts and understanding or finding words.

Symptoms develop gradually, often before age 65. They get worse over time. People with primary progressive aphasia can lose the ability to speak and write. Eventually, they’re not able to understand written or spoken language.

Not all people with primary progressive aphasia have dementia, but most develop it. The term ‘dementia’ is typically not used until a person can’t do things alone due to changes in their thinking and understanding.

<!- – ad: https://mads.dailymail.co.uk/v8/us/health/none/article/other/mpu_factbox.html?id=mpu_factbox_1 – ->

Advertisement

‘Picture yourself in a maze. You only know what you’re seeing in front of you. But you don’t know what’s happening around the corner or where you should go. Navigational skills are non-existent,’ she says.

The medical odyssey that followed the ‘boiling eggs’ incident proved as frustrating as the symptoms themselves.

Despite being taken to hospital, doctors initially dismissed her symptoms as anxiety, recommending epilepsy medication before discharging her – a decision her own family doctor found alarming.

‘When I returned home, the forgetfulness happened again. Then, the next week, my doctor called me said, “I got your test results and your your brain is swollen, you need to get an ambulance as ASAP. This is dangerous.”‘

Yet, upon her return to the hospital, her struggles were once again undermined. Physicians told her, ‘There is nothing wrong with you.’

‘Some doctors need a course in sympathy and effective communication,’ Natalie observes pointedly.

The back-and-forth between the hospital and her doctor continued, until a neurologist eventually suggested seeing a psychologist – which was a waste of time.

‘My speech was declining even more, and I just said to my doctor I needed to see a speech pathologist. So she wrote me a referral,’ Natalie explains.

Finally, a glimmer of hope. After being bounced between medical doctors, it was the speech pathologist who immediately recognised the constellation of symptoms.

They suspected she had a rare form of frontotemporal dementia known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA).

Following extensive testing, the suspicions were confirmed, and in 2021, at the age of 48, Natalie received her diagnosis.

PPA, a form of dementia, gradually erodes a person’s ability to communicate, with symptoms worsening over time.

For Natalie, the diagnosis offered a critical understanding of her changing brain.

‘It’s like the brain sometimes doesn’t connect the words I’m trying to say. I’m wanting to express them, but they’re not coming out,’ she explains.

‘It’s a roller coaster of emotions without knowing where that roller coaster is going to go next.’

Despite the profound challenges to her communication, Natalie is resolute.

‘I haven’t changed as a person. But what has changed is just the communication part of my brain.’

She stands as living proof that dementia discriminates against no one, striking without family history or known cause, and regardless of age.

Last year, before sharing her story publicly, a professor remarked, ‘You don’t look like you have dementia.’ Natalie responded: ‘What does dementia look like?’

Her mission is to dismantle stigma, encourage respect, foster understanding and champion hope amidst the complexities of living with a neurological condition.

She implores others to exercise patience and recognise the profound truth of her experience.

‘I’m the same Natalie with the same wants, needs and interests. What’s changed is how I communicate. I need to stop and collect my thoughts before speaking,’ she says.

‘I am going to live the best I can for the rest of my life. Even though I have these challenges, and I acknowledge them. Some days are harder than others, but even in those days, I try to find something positive.’

Natalie now attends regular speech pathology appointments to navigate her communication challenges.

While there is no cure for PPA, she actively engages in mentally stimulating activities, keeping fit and pursuing passions that evoke emotion, such as painting and listening to music, to challenge her brain.

Today, she travels across Australia and internationally, speaking at conferences. Later later this month, she will attend a Dementia Arts Festival in Scotland.

She is also a member of the Dementia Australia Advisory Committee.