He immediately understood the stakes: Either he had to swear off this euphoria or go all-in and let it kill him.

He swore off it. Briefly.

Such a 180 is a main theme of the book, and Sheen pre-empts any finger-wagging by admitting it early and often.

“At some point everything’s negotiable,” he writes.

The memoir is a curious amalgam: at first, a touching family history that lionises his A-list father, Martin Sheen; then a starry-eyed chronicle of shooting to fame after craving the adulation that his older brother, Emilio Estevez, had found in Hollywood; and, finally, an addiction memoir.

In that way, The Book of Sheen will no doubt draw comparisons to the autobiography Matthew Perry published in 2022, a year before he died of a drug overdose.

But if Perry revealed himself to be a sad clown, hiding his torment behind punch lines, Sheen is a different kind of stereotype.

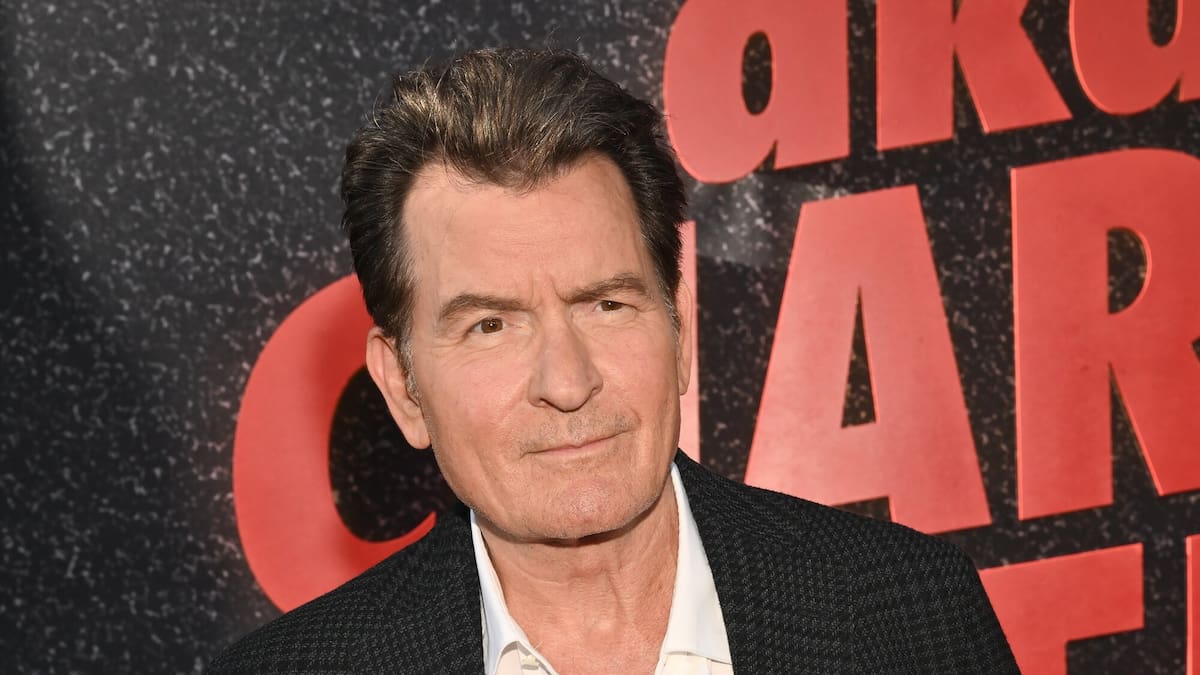

The actor, now 60, perfectly embodies the role of charismatic addict, a person who wields his easy charm to score his next fix.

In the book, Sheen writes that he’s been sober since 2017. So what is it he seeks? The evidence appears to point to a second (third? fourth?) chance at making it in show business.

His memoir release coincides with a Netflix documentary and a massive press tour rehashing, in part, what happened 14 years ago, when Sheen had a multiplatform meltdown after getting fired from Two and a Half Men.

Rather than shrink from the ignominy, he launched a press tour and a stage tour and discovered the magic of Twitter, spreading the message far and wide that he had “tiger blood” and “Adonis DNA”.

His catchphrase – “Winning!” – ironically became the perfect sarcastic response to any epic fail.

How did all that happen? Sheen writes that he had sworn off crack and booze by then, but he was still slathering on testosterone cream “in mind-altering gobs”.

Charlie Sheen’s new memoir, The Book of Sheen. Photo / Gallery

As is the case through much of the book, the actor is laid-back about how readers might process this information.

“Not making excuses or asking for a pass,” he writes, “just putting it out there as a detail that may have been confused with a laundry list of other potential suspects”.

He also draws attention to the hangers-on who, rather than telling him to step away from the spotlight, encouraged him to self-immolate onstage every night during a nationwide tour called; “My Violent Torpedo of Truth/Defeat Is Not An Option”.

“I do have to own the fact that it does take two to tango,” he writes, “though in that situation it actually felt more like two thousand”.

Still, he appears to bear few grudges. (One conspicuous exception is the one he harbours against “classless bully” O.J. Simpson, who becomes a running joke in the book for the evil glee he took in besting young Charlie at ping-pong.)

The women in Sheen’s orbit, especially, can do no wrong.

The drug-dealing nurse who introduced him to his first recreational intravenous drug? “A lovely gal.”

The girlfriend to whom Sheen had to pay $200,000 after an altercation that, the actor claims, she started?

“I really dug that girl.”

The escort who slapped his stomach and called him “fatso,” sending him straight to a “lipo doctor”?

“She was wonderful.”

If Sheen grants forgiveness easily, he also extends that courtesy to himself. He doesn’t appear to be drowning in regrets.

He spends a fair amount of time examining a moral dilemma he had about whether to take the lead role in The Karate Kid (he’d been offered the part, but had already signed on to get eaten by a grizzly in a slasher flick) and pats himself on the back for making the honourable choice.

He spends less energy unpacking why he wasn’t present for his first child’s birth in 1984. “After a goodly amount of soul-searching, I came around a bit later,” he shrugs.

If there’s one past action that still seems to bother him, it might be testifying against “Hollywood Madam” Heidi Fleiss during her trial for tax evasion in the 1990s.

Fleiss had facilitated many blissful nights for Sheen, and he seems to lament losing what he calls “the greatest arrangement ever,” and the fact that he and Fleiss haven’t spoken since.

That being said, he was impressed with some of the jokes that were flung his way afterward.

Given how readily Sheen shares some details from his past – there’s a whole bathroom incident that doesn’t need to be in the archives – it’s easy to lose sight of what’s left unwritten.

Sheen’s first fiancee, Kelly Preston, who went on to marry John Travolta and died in 2020, gets roughly a sentence. And there’s no mention of the strange incident with a gun that occurred shortly before their breakup.

Sheen similarly sheds little light on how his family reacted to his “tiger blood” rants, beyond the parenthetical aside that his father “was overseas with Emilio, promoting a film”.

That movie, The Way, was directed by Estevez and starred Martin Sheen as a father who channels his grief into a trek along the Camino de Santiago. The juxtaposition between that wholesome project and whatever Charlie Sheen was up to couldn’t have been starker at the time.

Since going public with his HIV diagnosis in 2015, Sheen has been dogged by rumours that he has had sex with men.

He does cop to that in the book, though the admission is buried within an extended metaphor involving a dinner menu, with women on one side and guys on the other.

“I finally said [screw it], and flipped it over to see what all the fuss was about,” he writes.

“They had to close down the whole restaurant for a very private party. When I poured bacchanalian exhilaration on top of Bananas Foster and hit puree on the Eros blender, the ‘other side of the menu’ was catering the event.”

That vivid yet confounding description is a good sample for a memoir that includes the sentence; “As long as I kept wearing hamburger pants on safari, I couldn’t complain about being attacked by a lion”.

And yet, such zaniness only adds to the entertainment value of a book that unfolds as a series of absurd stories laced with self-effacing humour.

Sheen is a good hang (despite his insistence on using “kool,” “dood” and a frequently deployed expletive uniquely spelled with two Ks), and he has the friend roster to prove it: Slash, Nicolas Cage, Mira Sorvino, Alan Ruck, C. Thomas Howell, Reggie Jackson, the yoga guru Bikram Choudhury.

The list goes on and on, even including Chuck Lorre, the Two and a Half Men creator who fired Sheen back in 2011.

Anyone who’s been acquainted with an addict knows what these people have likely been through – watching Sheen spiral and rebound, wondering if they should cut him off, then getting drawn back in.

In the end, on the page as in life, it’s hard to say no to Charlie Sheen.