A Nasa rover has uncovered the most compelling evidence yet that Mars may once have supported life.

Perseverance’s discovery involves tiny specks of minerals arranged in distinctive patterns, which on Earth are associated with living microbes.

The minerals have been preserved in rocks that were formed billions of years ago from the sediment of a river, which once fed a now-vanished lake. For scientists, the samples provide a snapshot of an ancient, watery world — Mars as it was before it was stripped of its atmosphere and became the largely barren planet we now see.

Sean Duffy, the acting Nasa administrator, said: “A year ago, we thought we found what we believe to be signs of microbial life on the Mars surface… we put it out to our scientific friends to pressure test it, to analyse it -– did we get this right? Do we think this is a sign of ancient life on Mars?

“After a year of review, they’ve come back and they said: ‘Listen, we can’t find another explanation. So, this very well could be the clearest sign of life that we’ve ever found on Mars.”

Professor Sanjeev Gupta of Imperial College London, co-author of the study, said: “It’s not a slam dunk by any means. But this is the most exciting evidence so far. For the first time, we have features that can be explained by biological processes.”

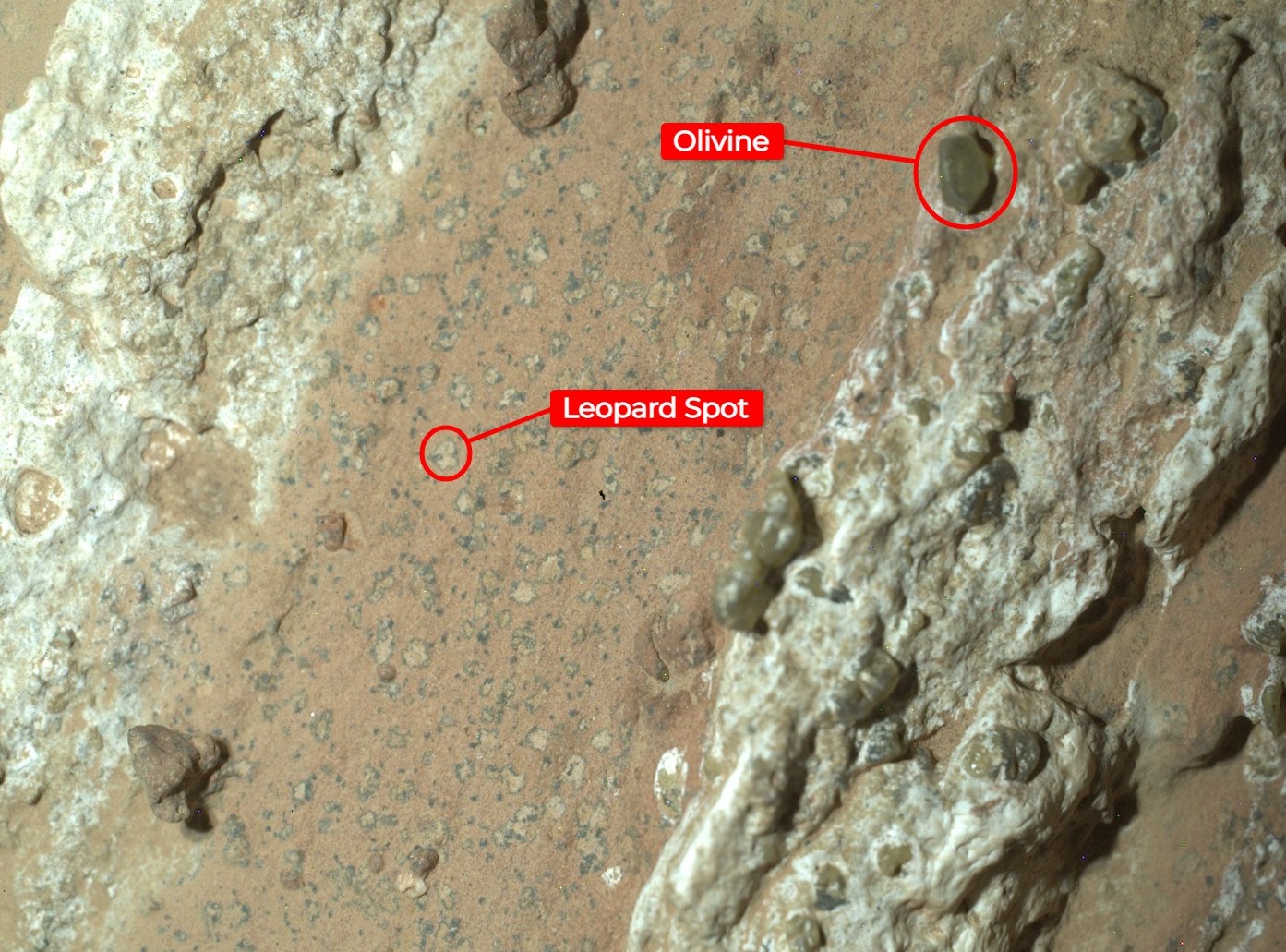

The rocks contain tiny dark specks, each less than a millimetre across, which have been nicknamed “poppy seeds”, as well as larger dark-rimmed rosettes with lighter centres, known by the researchers as “leopard spots”.

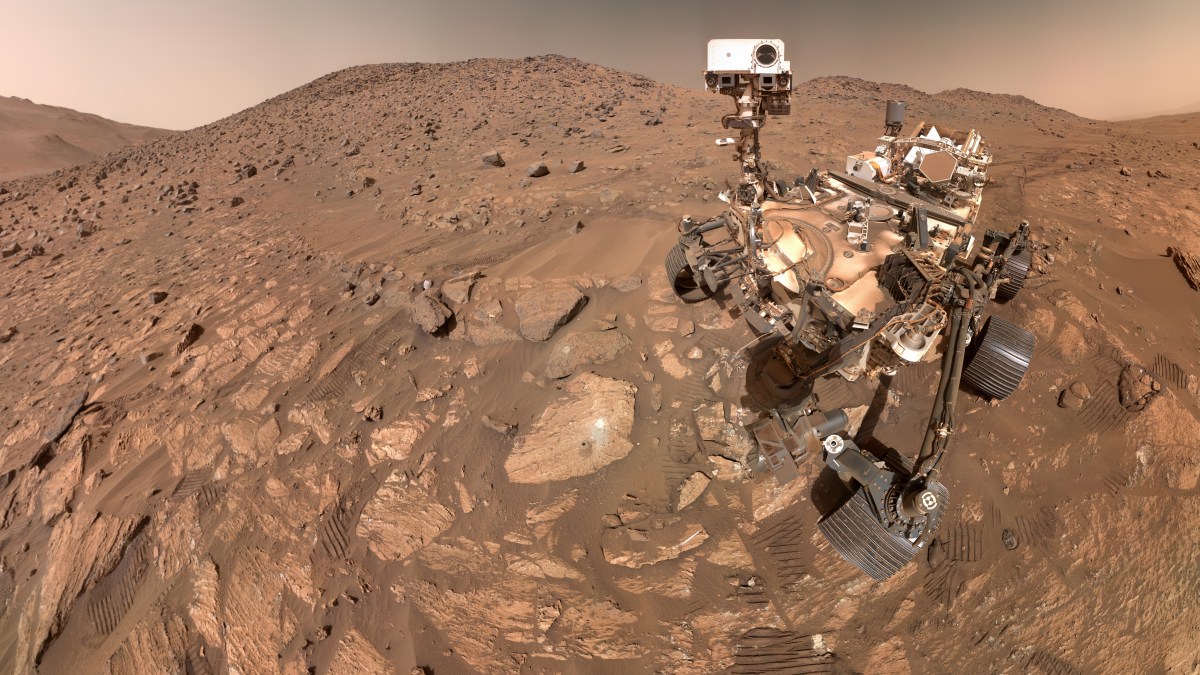

The samples were found years ago, seen here before extraction

NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS

Analysis by instruments on board Perseverance, a car-sized rover, has shown that the poppy seeds and the rims of the leopard spots are rich in iron and phosphorus, while the centres of the leopard spots are rich in iron and sulphur.

Scientists believe these patterns formed when carbon-rich organic compounds in the rock triggered redox reactions, in which electrons were transferred between minerals, changing their chemical state.

On Earth, similar reactions are driven by the metabolism of living microbes in freshwater and marine environments, raising the possibility that the Martian features are a record of biological activity. “Minerals like these … provide some of the earliest chemical evidence for life on Earth,” the research team explain in a paper published in the journal Nature.

• Mars may harbour life in vast underground reservoir

It is also possible that on Mars these features formed through purely chemical processes over millions of years. However, the reactions appear to have occurred at cool temperatures, which potentially tilt the balance towards a biological origin.

The age of the samples collected by Perseverance is not known exactly, but one estimate puts them at 3.5 to 3.7 billion years old — dates that would roughly align with the earliest evidence of microbial life on Earth.

The rover took its sample after landing on the planet’s Jezero Crater, seen here

NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS

Professor John Parnell of the University of Aberdeen, who was not part of the most recent study, agreed that the findings were significant. “On Earth, you find these sorts of [features] in places where microbes have been active,” he said, adding that they are not known to occur through other means.

In fact, scientists from Aberdeen were in touch with Nasa when the Perseverance mission was being planned. Among the materials they sent were photographs of very similar redox patterns left behind by microbes, which can be seen today on rocks near the town of Millport on the island of Great Cumbrae, off the coast of mainland Scotland.

Nicky Fox, head of science at Nasa, said: “This finding, by our incredible Perseverance rover, is the closest we’ve actually come to discovering ancient life on Mars… It’s kind of the equivalent of seeing leftovers from a meal, and maybe that meal has been excreted by a microbe — and that’s what we’re seeing in this sample.”

Matthew Cook, head of space exploration at the UK space agency, which has supported Gupta’s team at Imperial, said: “While we must remain scientifically cautious about definitive claims of ancient life, these findings represent the most promising evidence yet discovered.”

The Martian sample was gathered by Perseverance after it landed on the planet’s Jezero Crater region in 2021. It is stored, along with a number of rock cores, and sealed inside the rover, awaiting a potential trip back to Earth.

Tracks left by the rover on the surface of the red planet

NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS

Nasa’s plans to return the samples from Mars have been paused by President Trump’s administration and are a casualty of ballooning costs. The Mars Sample Return programme, described as the most ambitious robotic mission attempted, was originally supposed to ferry samples collected by Perseverance to Earth by the 2030s. However, the timeline slipped into the 2040s and the estimated cost increased from about $3 billion to $8-11 billion.

Speaking at a press conference on Wednesday, Duffy insisted the plans had not been abandoned. “We’re looking at how we get this sample back,” he said. “We believe there’s a better way to do this, a faster way to get these samples back… the president loves space.”

If the rocks ever make it back, scientists could use laboratory instruments far more powerful than those on the rover to examine the minerals in detail. Isotopic analyses, for example, could potentially reveal whether the mineral patterns were shaped by life or by chemistry alone.

Even if the specks ultimately prove non-biological, they reveal a planet of previously unappreciated complexity — where water, minerals, and organic compounds interacted in ways that could, in principle, support living organisms.

“Before you can find life, you need to find a habitat for it to inhabit,” Parnell said. “What we have here, at the very least, is the potential for a habitat. That’s a conservative way of putting it. And every possible habitat on the Earth has been colonised.”