When Peter Emerson arrived with his Brompton folding bicycle in the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan last January, he was daunted by the mountainous terrain. But as he started his journey, a local told him that if he followed the steep road ahead it would soon be flat.

“Not at all. I was pushing the bloody bike the whole time. So I got very tired,” he told me over coffee in Beijing this week.

“Then, fortunately, another cyclist came along, a much younger guy than I. We cycled together and he helped me carry one of my bags.”

Short, spry and 82 years old, Emerson is about to go home to Belfast after eight months on the road that took him all over China, visiting almost a dozen provinces as well as Tibet and Xinjiang. He didn’t cycle all the way but would take the train to a town or city, dump all his luggage and cycle from there into surrounding villages where he would say hello to the people there.

“Of course, some of them had never seen a foreigner before. They certainly hadn’t seen such an old one on a bicycle. Then I’d ask to see a member of the village committee,” he said.

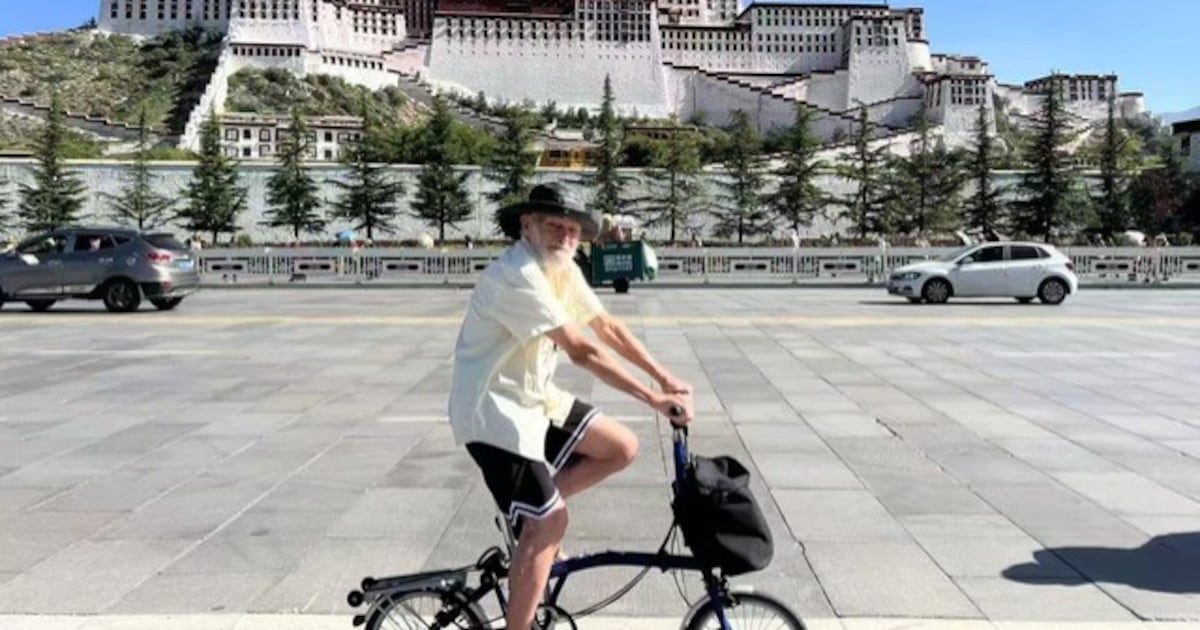

Peter Emerson in Yunnan province. Photograph: Courtesy of Peter Emerson

Peter Emerson in Yunnan province. Photograph: Courtesy of Peter Emerson

Many of the villages are as big as small- to medium-sized towns in Ireland, with thousands of inhabitants. Held every five years, elections to village councils are often competitive and candidates do not have to be members of the Communist Party, although the chair is usually the local party secretary.

“Sometimes they use approval voting, which is brilliant. It’s much better than first past the post,” Emerson said.

“You have a list of candidates, and you just tick this one, this one, this one. You might be allowed three ticks, depending on how many people they’re electing. It’s quite a good system. It was used quite extensively in Europe during the Middle Ages.”

Emerson’s success rate in engaging with the village councils was varied, with smaller places in rural areas more welcoming than more urban districts. Sometimes the police would show up to ask him who he was and what he was up to.

[ New global order? Modi, Putin and Xi offer glimpse of what may lie aheadOpens in new window ]

“A friend that I was staying with had quite a few problems with the police after I had gone, getting phone calls asking where’s he gone and all that nonsense. Just harassment. It’s very bloody annoying, actually,” he said.

An expert in electoral systems, Emerson heads the Belfast-based de Borda Institute, which promotes the use of multi-optional and preferential voting procedures for legislatures and for referendums. He cites Brexit as a contentious issue where voters should have been offered a number of options rather than a binary choice.

“The United Kingdom could have been in the EU or the EEA or the Customs Union or the World Trade Organization. There were four options at least,” he said.

“If you vote for only one option, you only get one point. If you vote for three options, you get three to one points, and a vote for all four. It is encouraging people to participate. But if everybody does cast their four preferences, then you can find the option with the highest average preference. An average includes everybody and not just a majority. This system, the Modified de Borda Count, is post-majoritarian.”

In Xinjiang he came across a village with seven ethnic groups where they used a system of proportional representation to elect the village council. But when he asked how decisions were made, he was told “the minority obeys the majority” and that was the principle he saw in operation everywhere he went.

[ The tourism boom in China’s pariah provinceOpens in new window ]

“They are trying to be democratic in a very limited sense in the same way that we do,” he said.

“Questions about turnout were never answered, often not asked because it was just too sensitive. But when you meet a policeman and ask, did you vote? He says no. But that’s the same in the West. It’s almost like a facade, as if they are being democratic. But in the West, it’s a bit of a facade as well.”

Peter Emerson in Beijing. Photograph: Denis Staunton

As he prepared to go back to Belfast after eight months in China, much of it peddling his Brompton bike, Emerson told me that his friends and family thought his venture was crazy.

“My health has stood up, which at this age is a fairly important fact,” he said.

“At the moment I’m okay. And the bike’s okay, which is probably even more amazing.”