At a 50th birthday party last weekend the conversation turned, with grim inevitability, to AI and how it is going to steal our jobs. A friend who I had not seen for a while explained, however, that it was proving a lifesaver.

“I’ve been using ChatGPT to work out whether I have grounds for constructive dismissal.” Seriously? Yes, she said. She had uploaded a few emails from her boss, which she thought were proof of harassment, and ChatGPT had spat out an answer, citing case law, and a suggested letter to send to HR.

I suspect that her experience is not unique. Indeed, the ability of generative AI to parse complicated legalese may explain why we have seen an increase in employment tribunals over the past year.

• Help! I’m addicted to ChatGPT

Tribunal trends are tricky to pin down, mostly because fees to bring a case — which used to sometimes reach more than £1,000 — were scrapped in 2017. This caused a spike in claims, then Covid led to a backlog. In the past three years, though, they have increased and rose from 34,000 to 42,000 in the year to March 2025.

Has the workplace suddenly become more toxic? Are there more racist bosses or sexist managers than a few years ago? This seems unlikely.

So something else is causing these tribunals. A key factor is the state of the economy and Rachel Reeves making it more expensive for organisations to hire workers. It is probable that some employers, in order to cut costs, are axing staff and, in some cases, doing it carelessly, leading to workers fighting back through the courts.

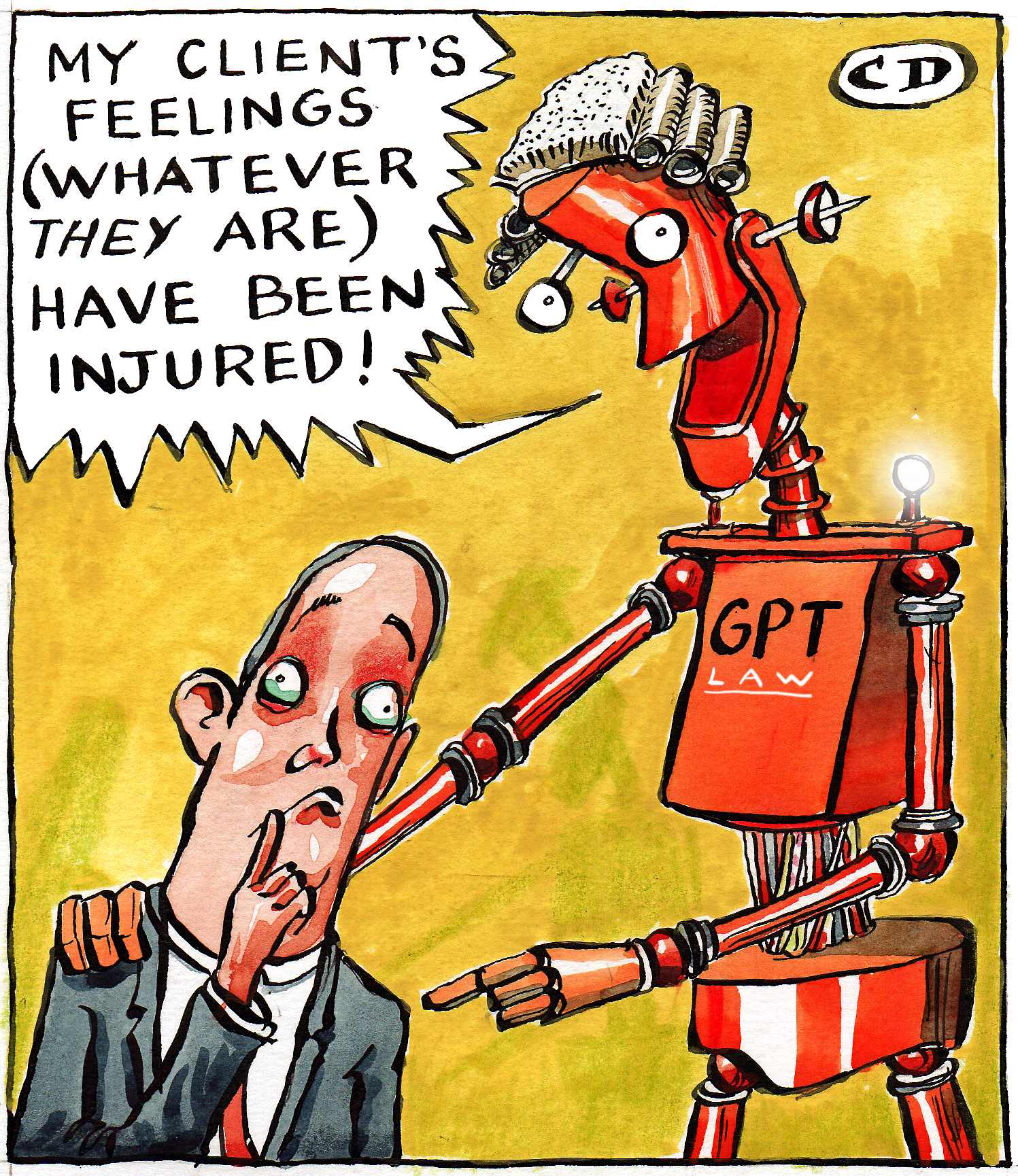

Could AI also be a factor? I am not the only one to believe that it might be. John Hayes is founding partner of Constantine Law, an employment law specialist. He says he is seeing an increasing number of claimants who are strangely well informed about both their rights and the procedures involved in bringing a case. “I think ChatGPT will do for law what the internet did for journalism: everyone can become a lawyer now,” he said.

This is not a bad thing. Justice should be available to all but there is a fear that it could also encourage claims that, although technically correct, stretch the capacity of tribunals and the law itself to breaking point.

A few hours spent on the Employment Tribunal website leaves you with the impression that it is a miracle, frankly, that Britain’s workplaces get any actual work done.

Recently there was the car salesman who quit after a mere three weeks claiming that the conduct of some of his fellow workers — making sexist comments about women that he overheard — “had the effect of violating (his) dignity and creating an offensive environment for him”, according to a judge. He won his case for sexual harassment.

Then there was the Rickmansworth estate agent awarded £21,000 after he was told to sit at a desk that “undermined his status” because it was not at the back at the office, where traditionally the branch manager sat.

Some of the less prominent cases are in many ways more revealing. Let me tell you about Andrej Ziga vs Anglian Windows.

Ziga worked at this Norwich-based double-glazing company for a decade. He was dismissed for gross misconduct after allegations that he angrily shouted at and was insubordinate towards his line manager in 2022. For the following year he was in dispute with the company but failed to attend a number of disciplinary hearings “by reason of depression, back pain and work-related stress”. He was eventually dismissed in April 2023.

He sued for unfair dismissal and claimed that the company had failed to make reasonable adjustments for his disability, which by law an employer must do. He said he suffered from depression and anxiety, psoriasis, hypertension, psoriatic arthritis, vitiligo and spondylitis. The judge found that he was depressed for a period in 2020.

It is a complicated case with 852 pages of witness statements and doctors’ notes and the hearing took seven days but it all boiled down to a mere four night shifts. Because of Ziga’s depression, Anglian had agreed that he could work ten-hour shifts, not the normal 12-hour ones. On four occasions he was made to work 12-hour ones. The judge ruled, and you can sense his frustration, that: “Mr Ziga was angry, but he was angry about a lot of things.”

Ziga lost many aspects of his case but this week he was awarded £4,000 for injury to feelings, plus interest of £1,494, because the four night shifts took place in 2020.

• Managers turn to AI chatbots for advice before bosses

The colossal amount of time, energy and lawyers’ fees involved in reaching this conclusion were not unusual. Many employment tribunals involve huge bundles of evidence, including doctors’ notes and tortuous arguments over a worker’s mental health.

Hayes at Constantine Law talked about an increasing “grievance culture” in the UK workplace, made worse partly by an “unholy alliance” between GPs and workers, “whereby it is all too easy to get signed off for anxiety”.

AI, still in its early days, will almost certainly ratchet up the volume of claims but so too will the implementation of the Employment Rights Bill working its way through parliament. This will allow workers to sue for unfair dismissal from day one, not the current two years. Hayes predicted that cases already taking 18 months to come to a tribunal will now have to wait two to three years.

The unions successfully scrapped fees for employment tribunals, making it easier for workers to sue their employers, but without some form of quality control the entire employment tribunal system risks grinding to a halt. This would be bad for workplaces trapped in Dickensian disputes with aggrieved workers but also pretty terrible for British workers, some of whom have legitimate grounds to seek justice.