Woodworking. You are safe if you are skilled at woodworking. That was the startling answer I received a few months ago to the one question I ask any AI start-up founder or engineer I encounter these days.

The question: what do you tell your kids to study? In a world where none of them will, in the words of OpenAI’s Sam Altman, “ever be smarter than a machine”, how do you set your progeny on a course where they do not end up surplus to requirements in this new world?

Most give hazy, techno-optimistic responses. The future is going to be awesome! AI is going to generate swathes of new jobs that, with our tiny minds, we cannot conceive of today!

The woodworking answer, however, stuck with me. Partly because it was so specific, but also so, well, analogue.

Since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, the jobs question has been an object of fascination and growing angst among politicians, regulators and executives. What does the future hold for us humans when bots can best the world’s top mathematicians, create websites with a text prompt, provide relationship advice and handle our taxes?

Nearly three years on, something of a picture has begun to emerge. First came last week’s stunning reduction in official employment numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, showing that America actually generated nearly one million fewer jobs last year than previously estimated. The revision added fuel to a debate that began raging last month, when two studies rippled through Silicon Valley for their wildly differing takes on the present and future of work.

OpenAI brought us ChatGPT, and chief executive Sam Altman believes no humans will be as smart as artificial intelligence

NATHAN LAINE/GETTY IMAGES

The first was a report from researchers affiliated to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). They concluded that companies that had tried AI in their businesses found it to be, mostly, worthless. “Despite $30 billion to $40 billion in enterprise investment into generative AI, this report uncovers a surprising result in that 95 per cent of organisations are getting zero return,” the authors wrote.

One could almost hear the collective sigh of relief among white-collar professionals, from accountants to coders to journalists. Phew! Maybe this whole AI thing is not going to be such a world-changer after all. My job is secure!

The report argued that companies were eagerly testing out new AI tools — but then binning them. “Only a small fraction of organisations have moved beyond experimentation to achieve meaningful business transformation,” it said.

However, many quickly pointed out that the 95 per cent figure was not backed up by data. And the methodology — no official company data, but rather interviews with individuals at 52 anonymous organisations that had piloted AI tools — left something to be desired. It was, in a word, flimsy, wrote Kevin Werbach, a professor at Pennsylvania University’s Wharton Business School.

“AI sceptics were looking for evidence to support their suspicions, and they thought they had found it,” he said, adding: “The incident is, frankly, a great example of confirmation bias.”

And then the other report came out.

A 57-page missive from Stanford University’s Digital Economy Lab reached a very different conclusion. Researchers gained access to millions of monthly payslips from ADP, America’s largest payroll processor, between late 2022, when ChatGPT launched, and July 2025. They found “a significant and disproportionate impact on entry-level workers” in “AI-exposed” jobs such as accounting, software development and customer service. “Occupations with a high share of college graduates have declining employment overall,” they wrote.

The fall was most acute — 13 per cent — for young workers (aged 22-25), and was most heavily weighted towards sectors where AI automates work, completing tasks with little human input, rather than augments it.

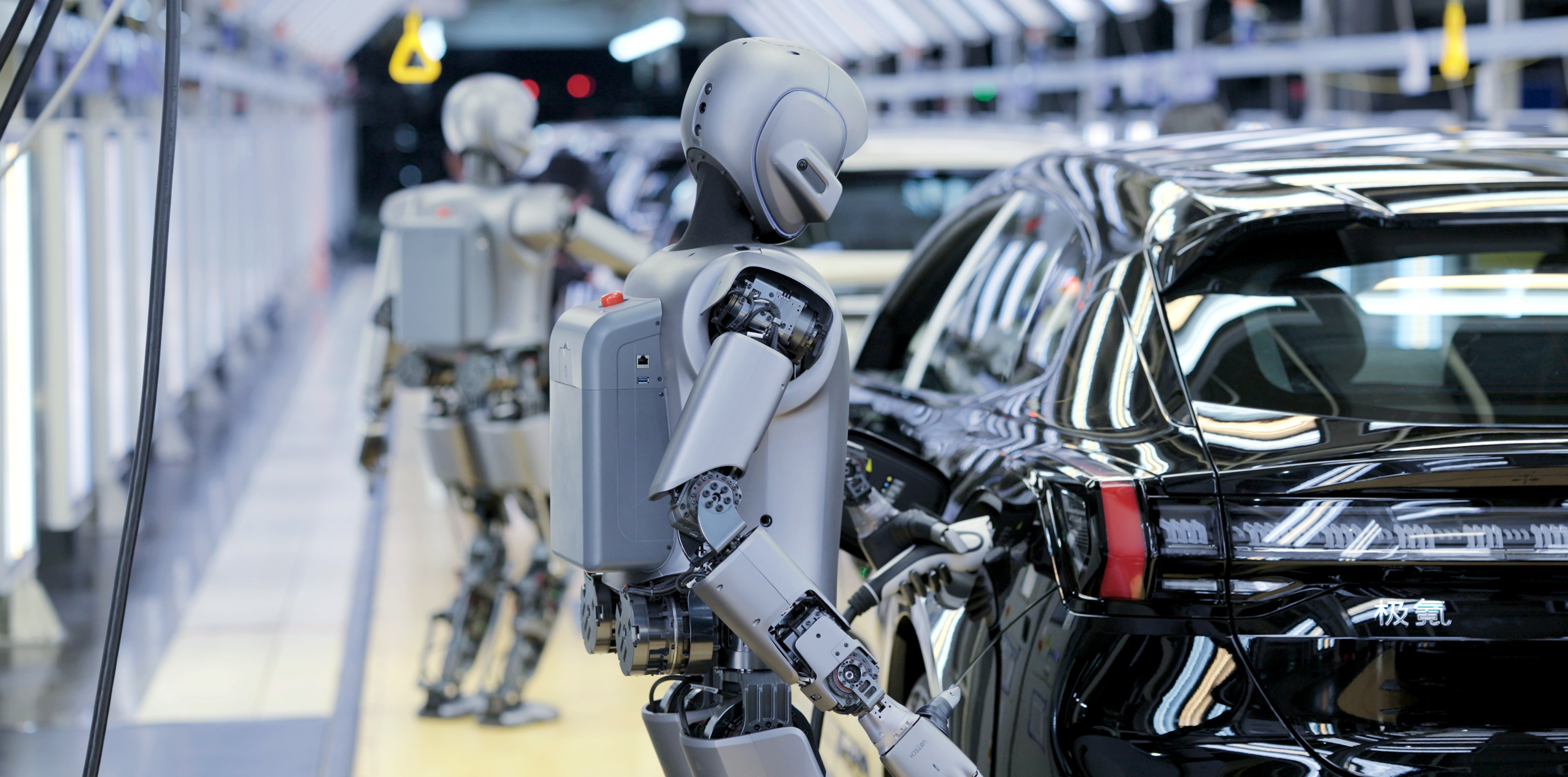

Robots build cars in Ningbo, China, and below, on show in Taiwan. But AI is not yet equipped to do everyone’s jobs, with skilled trades and healthcare among the professions where the human touch still reigns

GETTY IMAGES

The conclusions added ballast to the headline-grabbing warning in May by Dario Amodei, chief executive of Anthropic, developer of the popular Claude chatbot. He predicted that AI could wipe out half of entry-level white-collar jobs and spike unemployment to 20 per cent within five years. “We, as the producers of this technology, have a duty and an obligation to be honest about what is coming,” he said. “I don’t think this is on people’s radar.”

Increasingly, though, it is, as large language models improve and amid anecdotal evidence of young people struggling to find work — evidence that very often takes the form of tearful to-camera TikTok videos. Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab appears to have backed up those anecdotes with data.

Even as employment in America has grown since 2022, its report found that the job market for young people has stagnated. It makes sense that they are the early cannon fodder for the AI revolution.

These job-conquering AI systems are very good at handling certain types of rote cognitive work that require “codified” knowledge such as that taught in university. But where they fail more often is in handling issues that require more nuance and deeper thought (although they are getting better here too). So it should come as little surprise that employment for more experienced workers has actually grown over the past three years.

This is perhaps, the researchers posited, because “AI may be less capable of replacing tacit knowledge — the idiosyncratic tips and tricks that accumulate with experience”.

The picture that emerges, then, is rather alarming: a generational divide between employable, higher-paid middle-aged people, and younger generations who have been micro-targeted by AI for a jobs recession. How do young people accumulate the “tacit knowledge” of their elders if they cannot even get onto the lowest rung of the employment ladder?

Erik Brynjolfsson, the lead author of the report, said his goal was to create an “early-warning system” for the economic effects, both positive and negative, of AI. “The days of going to college and staying in the same career unchanged for 40 years until you retire … I think those are gone,” he said. “This is by far the biggest societal challenge of the next five to ten years, and not enough people are taking it seriously.”

The issue is pervasive. In Canada, 14.6 per cent of people between the ages of 16 and 24 are unemployed — a 40 per cent increase in two years and the highest level since 2010. It is a similar story in Britain, where 14.1 per cent of 16 to 24-year-olds are out of work.

There are other factors at play, such as high interest rates, which have made money more expensive to borrow and led to companies becoming more circumspect about spending. Donald Trump’s trade war has also injected a level of uncertainty into the economy not seen since the pandemic, while policies such as Rachel Reeves’s national insurance hike are also thought to have affected recruitment.

Jack Kennedy, senior economist at the jobs website Indeed, said: “UK graduate job postings this year are trending at the weakest since at least 2018, barring 2020 at the height of Covid. However, it’s unclear the extent to which this is due to AI, rather than simply reflecting general economic conditions and uncertainty. Employers typically dial back their graduate hiring during such periods, as we have seen in the past.”

• A thousand applications to get a job: the graduate grind

In the background, however, tech firms are ploughing hundreds of billions of dollars into the data centres that power what is, in effect, a growing army of digital workers. That spending spree is why, even as young people feel the brunt, mid-career workers should not be complacent, Brynjolfsson said. As AI capabilities improve, the bots are likely to move up the chain to more high-value, complex jobs. To wit, in just one year, between 2023 and 2024, top AI tools went from being able to solve just 4.4 per cent of problems in a software coding benchmark exam to 71.7 per cent.

“AI has already surpassed human performance across many tasks, with only a few exceptions,” read Stanford University’s annual AI Index report.

In practical terms, that means companies can do more with less. Satya Nadella, chief executive of Microsoft, put a fine point on the “incongruence” between two realities. The software giant is doing better than ever, posting record profits and sales — but Nadella has also jettisoned 15,000 people this year.

“This platform shift is reshaping not only the products we build and the business models we operate under, but also how we are structured and how we work together every day,” he said. “It might feel messy at times, but transformation always is.”

There is hope, though, amid the march of the machines. Consider the kerfuffle that OpenAI and Google DeepMind caused in July when they announced that their leading-edge models had scored unofficial gold medals — the AI tools were not actual contestants — in the International Mathematical Olympiad, an annual contest for the world’s brightest maths minds.

• Google’s DeepMind AI wins silver at International Maths Olympiad

Another industry vaporised by Silicon Valley?

Not likely, wrote Kevin Buzzard, a maths professor at Imperial College London and an IMO gold medallist himself. “When I arrived in Cambridge as an undergraduate clutching my medal, I was in no position to help any of the research mathematicians there,” he said. His point: intellectual horsepower may be good for winning contests, but it does not necessarily equate to productivity, sound judgment or creativity.

Indeed, one bright spot found by Brynjolfsson was that workers who use AI to augment — iterating or improving ideas, rather than relying on them to handle tasks autonomously — have actually held up rather well. And some jobs have proved impervious, from psychiatric and nursing care to cooking, welding and manual labour.

It’s not all bad newsNurses/healthcare professionals: Several start-ups are working on empathetic robots for hospital settings, but so far no company has come up with a machine that can administer medication, manage patient care or change a bedpan.Skilled trades: Whether it is roofers, welders or electricians, skilled trades have grown strongly and appear in no danger of being automated away. Drivers: Robotaxis from the likes of Waymo have begun to show up on the streets of California and Texas, but any real dent in human drivers is expected to be many years off — if it ever happens at all. Emergency services: Police forces and firefighters may utilise AI tools to help them track down criminals or spot fires sooner, but the machines can’t do what they do. Generative AI consultant: This position, which helps companies adopt and leverage AI tools, is one of what is expected to be a crop of new jobs created by the introduction of this technology across the economy.

New jobs will also emerge. After all, podcasters, YouTube influencers, drone operators and sustainability managers are all professions that did not exist 20 years ago, before societal and economic forces delivered them. Allison Shrivastava, an economist at Indeed, said the “generative AI consultant” has emerged as a novel listing on its boards. “This job title, once unexpected, has seen rapid growth as organisations rush to experiment with AI.”

The question is, how long will this promised flowering of new opportunities take to unfold before AI eats the world? And how best to help today’s young people, who suddenly find themselves on the losing end of a competition with the machines?

Perhaps now is a good time to get acquainted with a chisel and mitre saw.