Golf fans driving the Southern State Parkway towards the Ryder Cup at Bethpage Black next weekend will notice the many bridges spanning it hang very low. There’s a reason for this engineering oddity.

In 1925, when Robert Moses oversaw construction of the road along Long Island’s south shore, he ordered them built to those specifications to ensure buses could never fit underneath. He wanted to make it as difficult as possible for Black New Yorkers to take day trips to nearby Jones Beach. The same man once commissioned 255 new playgrounds around the city and awarded one to Harlem.

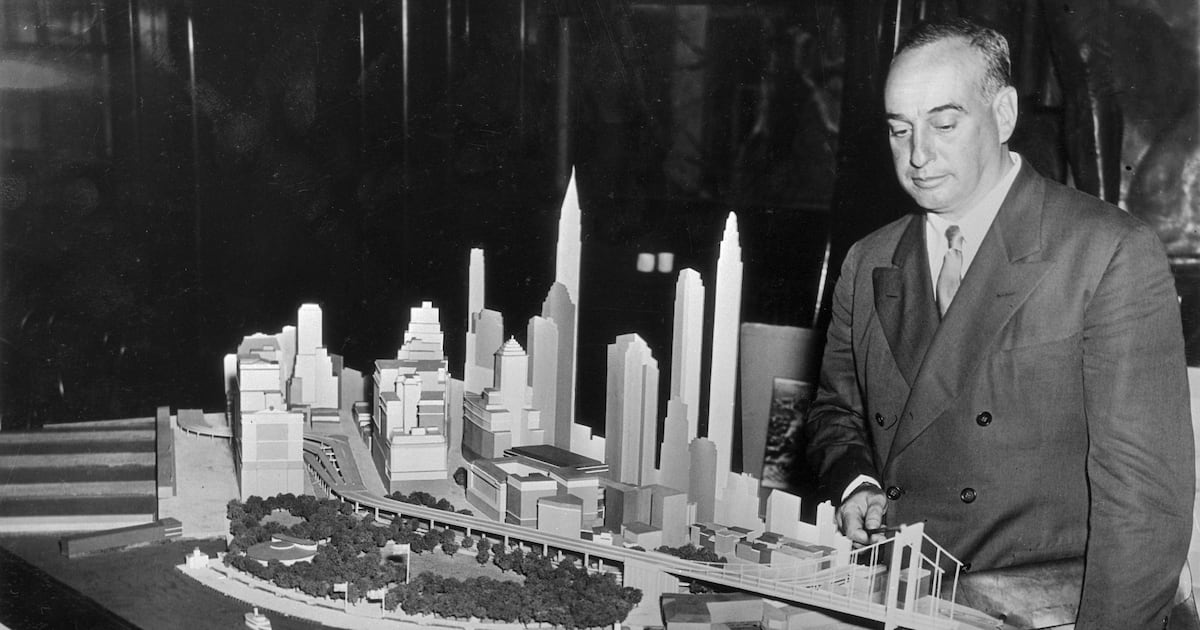

“Robert Moses was an utterly racist man and his racism was reflected in what he built,” wrote Robert Caro, author of The Power Broker, the definitive, exhaustive biography of the most influential unelected official in 20th century America. Moses was often described as the architect of modern New York.

When they arrive at sprawling Bethpage State Park, supporters of Europe and the United States can thank Moses, the visionary, eh, racist, for the sumptuous venue hosting this year’s contest. Aside from overseeing the building of umpteen bridges, roads and parks in and around the state, he conceived of this municipal golf facility now boasting five 18-hole courses.

Four of them, including Bethpage Black, the most prestigious and challenging, came into being in the 1930s when Moses, then president of the Long Island State Parks Commission, took a notion to create what he fancifully called “a people’s country club”.

The 2025 Ryder Cup will be played on the Bethpage Black Course, New York, from September 26th to 28th. Photograph: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

The 2025 Ryder Cup will be played on the Bethpage Black Course, New York, from September 26th to 28th. Photograph: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

Carved out of 1,398 acres of rolling hills known by the Native American Algonquins as “rim of the woods”, the location came with a convenient origin story.

This was where, in 1688, Kildare-born Thomas Dongan, future Earl of Limerick, reputedly played the first ever game of golf on American soil, against Thomas Powell, future founder of the town of Bethpage. Much was made of this dubious claim to sporting heritage on the day Moses formally opened the facility in 1936. It was replete with a polo ground, tennis courts and horse-riding. Moses declared it the finest public playground in the world.

In the early years, very few ordinary Long Islanders had cars to drive there or a spare $2 to play 18 holes. Despite this, Bethpage Black eventually became wonderfully democratic. An anomaly among America’s finest courses, it has hosted major tournaments yet always remained available to regular golfers on a first-come, first-served basis. If you are a New York resident willing to queue overnight for the privilege of a walk-up tee slot, it costs just $75 (€63). It is affordable and accessible most of the time. Just not next week.

The eyes of the world will be on Bethpage in New York for the 2025 Ryder Cup. Photograph: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

The eyes of the world will be on Bethpage in New York for the 2025 Ryder Cup. Photograph: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

The controversial decision to price tickets for each competitive day of the Ryder Cup at a saucy $750 guarantees only the wealthiest Long Islanders and invading hordes of Manhattan corporate yokels will be able to afford to see Keegan Bradley leading the home side against Luke Donald’s selection. Charging seven times what local punters paid to watch Brooks Koepka win the 2019 PGA Championship at the same venue ensures that.

“Bethpage doesn’t believe in equality, it is the embodiment of it – rich or poor, big or small, somebody or nobody; you can play,” wrote James Colgan on Golf.com. “A $750 Ryder Cup ticket fundamentally contradicts this idea. It tells us golf belongs to somebody instead of everybody. It suggests we come to grips with that reality and don’t complain. It separates those who love golf from those who can afford it. Bethpage has never been about haves and have-nots. It earned its favour precisely because it rejects golf’s less worldly ideals of elitism and exclusivity.”

A ticket to attend one day of the Ryder Cup costs $750, which is at odds with Bethpage’s inclusive tradition. Photograph: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

A ticket to attend one day of the Ryder Cup costs $750, which is at odds with Bethpage’s inclusive tradition. Photograph: Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

The exclusionary pricing is especially ironic because Bethpage was built by the poorest of the poor in the bleakest of times. Moses imagined his grand golf facility during the Great Depression when President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal also created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to bring relief to millions left unemployed and suffering following the Wall Street Crash. With posters assuring desperate Americans that “Work promotes confidence!”, WPA public works projects nationwide gave people gainful employment and a smidgen of their pride back building everything from roads to schools, swimming pools to golf courses.

[ Dave Hannigan: Why Samuel Beckett is a good fit for the New York MetsOpens in new window ]

Moses tapped eagerly into the WPA supply line and 500 or so labourers toiled every day at Bethpage, earning 61 cents an hour. During one threat of strike action, many complained that just getting to the park from their homes around the island and New York seriously ate into their already meagre wage. Known for bulldozing the poorer city neighbourhoods out of existence in the name of what he called progress, Moses had little sympathy for their plight. He once described mendicants sent to him by the WPA for this and other projects as “riff-raff, bums and jail-birds”.

The thundering snob had no qualms paying AW Tillinghast, architect of Winged Foot, Quaker Ridge and Baltusrol, among other storied tracks, $50 a day to bring his design talents to bear on this vision. Although he was contracted for just 15 days of work, Tillinghast – then struggling financially and battling a drink problem – initially got all the credit for the supreme quality of the Black course. It later emerged that most of the heavy lifting had been done by Joseph H Burbeck, superintendent of Bethpage State Park. Golf literature now reflects that reality, but the contribution of both men is nearly always dwarfed by that of Moses, the incorrigible racist who made it all possible.