It was ruthlessly hunted to extinction by humans over 300 years ago.

But scientists are one step closer to bringing the dodo back from the dead.

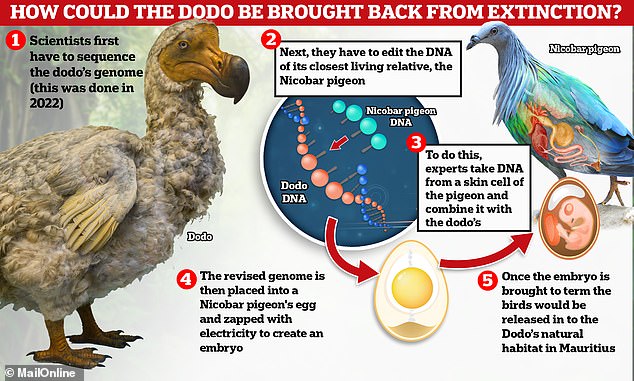

Experts at Colossal Biosciences, a ‘de-extinction company’ in Texas, have grown primordial germ cells of the Nicobar pigeon, the dodo’s closest living relative.

Primordial germ cells are simply stem cells that develop into either sperm or eggs.

Next, scientists are planning on editing these pigeon cells with dodo DNA, before transferring them to gene-edited chickens.

This should allow the chickens to lay dodo eggs that should allow for the once-extinct bird to live again by the turn of the decade.

Ben Lamm, chief executive of Colossal Biosciences, described the newest development as ‘a significant advancement for dodo de-extinction’.

‘Colossal’s investment in de-extinction technology is driving discovery and developing tools for both our de-extinction and conservation efforts,’ he said.

Scientists claim they are one step closer to bringing the dodo back from extinction. Pictured, a dodo model at the Natural History Museum in London

Scientists are using stem cell technology to bring back the extinct species – more than 350 years after it was wiped out

According to Mr Lamm, the growth of pigeon primordial germ cells is a world first, and a ‘pivotal step’ in bringing back the dodo.

Now this hurdle is cleared, he thinks the extinct species’ return will be as soon as five years from now, or as late as seven years from now.

The new dodos – the first to be born since the 17th century – will eventually be released in Mauritius, the island east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean.

Colossal Biosciences, which also wants to bring back the extinct woolly mammoth and Tasmanian tiger, has already partnered with The Mauritian Wildlife Foundation to find a suitable location for the first flock.

Eventually, Mr Lamm wants ‘thousands’ of dodos on Mauritius that have enough genetic diversity to protect them from any widespread disease.

However, experts have questioned whether the new birds would really be dodos at all, because of how challenging it is to 100 per cent replicate an extinct creature’s genetic code.

When the resulting chicks hatch, they may have a few differences compared to the original species.

Phil Seddon, professor of zoology at the University of Otago in New Zealand, hailed the firm’s ‘amazing technological breakthroughs’ but said extinction ‘really is forever’.

Most people believe that the dodo was a fat, ungainly bird, but as it has been extinct since the late 1600s, nobody really knows exactly what the dodo looked like

Dodo: Basic facts

Scientific name: Raphus cucullatus

Height: Three feet

Weight: 23-39lbs

Range: Mauritius (Indian Ocean)

Habitat: Forests

Status: Extinct

<!- – ad: https://mads.dailymail.co.uk/v8/us/sciencetech/none/article/other/mpu_factbox.html?id=mpu_factbox_1 – ->

Advertisement

‘This involved advances in genetic technology, and these might have applications for the conservation of existing species,’ he said.

The dodo, discovered by Europeans in 1598, was a flightless bird that lived on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

It gets its name from the Portuguese word for ‘fool’, after colonialists mocked its apparent lack of fear of human hunters.

Unfortunately, the species became prey for cats, dogs and pigs that had been brought with sailors exploring the Indian Ocean.

Because the species lived in isolation on Mauritius for hundreds of years, the bird was fearless, and its inability to fly made it easy prey.

Its last confirmed sighting was in 1662 after Dutch sailors first spotted the species just 64 years earlier in 1598.

Most people believe that the dodo was a fat, ungainly bird, but as it has been extinct since the late 1600s, nobody really knows exactly what the dodo looked like.

Oxford University Museum of Natural History is home to the only surviving remains of dodo soft tissue that exists anywhere in the world.

Scientists said the ‘Oxford dodo’ was blasted in the back of the head with a shotgun.

The Nicobar pigeon (pictured) is the closest living relative of the dodo, found on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India

The dodo gets its name from the Portuguese word for ‘fool’, after colonialists mocked its apparent lack of fear of human hunters

Pictured, part of the ‘Oxford dodo’ – the only surviving remains of dodo soft tissue that exists anywhere in the world

There’s also a dodo upper jaw in the National Museum, Prague, and a dodo skull in the Natural History Museum of Denmark, from which experts at Colossal Biosciences extracted DNA.

Now, these scarce dodo fragments exist as a ‘symbol of man-caused extinction’, according to the company.

Since its launch in September 2021, Colossal Biosciences has raised just over $555 million (£406 million) in funding.

Among its high-profile investors include film director Peter Jackson, golfer Tiger Woods and American footballer Tom Brady.

Jackson is involved with the firm’s separate project to bright back the moa, the iconic extinct New Zealand bird.

WHY DID THE DODO GO EXTINCT?

Little is known about the life of the dodo, despite the notoriety that comes with being one of the world’s most famous extinct species in history.

The bird gets its name from the Portuguese word for ‘fool’ after colonialists mocked its apparent lack of fear of human hunters.

The 3ft (one metre) tall bird was wiped out by visiting sailors and the dogs, cats, pigs and monkeys they brought to the island in the 17th century.

Because the species lived in isolation on Mauritius for hundreds of years, the bird was fearless, and its inability to fly made it easy prey.

Its last confirmed sighting was in 1662 after Dutch sailors first spotted the species just 64 years earlier in 1598.

As it had evolved without any predators, it survived in bliss for centuries.

The arrival of human settlers to the islands meant that its numbers rapidly diminished as it was eaten by the new species invading its habitat – humans.

Sailors and settlers ravaged the docile bird and it went from a successful animal occupying an environmental niche with no predators to extinct in a single lifetime.