Bee Trudgeon has had a lifelong love affair with CS Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. In celebration of the book’s 75th year of publication, she explains why.

Although this year marks the 75th anniversary of the classic CS Lewis children’s novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I felt like it was already an ancient text when I first encountered it – circa 1980, in its 30th year of what has proven to be an evergreen season of publication.

Like the siblings in the book, I lived with my parents and three (of my four) siblings, in an old (although not nearly as large) house in the country, to which we had recently (reluctantly) relocated from our previous suburban life. My father’s work commitments, rather than the German air raids on London in World War II, were responsible for our uprooting to the middle of nowhere. I periodically headed off along the unsealed road that had brought us here, sights set on some nebulous, street lamp-lit concept of home, sobbing, convinced I could walk back to our former life. If there was ever a child in need of a magic portal, I was that child.

Luckily, most of the means of my escape were just waiting to be discovered, in the spooky “passage” between my bedroom and the rest of the house, lined with the books of a houseful of readers. From my early forays into chapter books, I leaned hard into the magical and mysterious. If a book had a witch or a ghost on the cover – or no dust jacket on its cloth-bound cover at all (surely a sign it had been read to bits) – I’d be in. At nine years old, I was a creature made up of equal parts belief, despair and wonder. My own personal Jesus helped with some of that. I had access to the key to the church across the road, where a life-size plaster statue of the son of God was my most reliable confidante. My mother assumed his name to answer all the letters I wrote and left on my pillow, when prayer didn’t seem direct enough.

Once weaned off the sealed suburban streets I’d spent my first eight years biking around, the sheep and cow paddocks and native bush of our new home proved ripe for dreaming. A steady diet of portal fantasy novels had me attuned to the possibilities hidden within those endless green acres of nothing to do. I would press my ear to the concrete base of the local monument to soldiers lost in World War I, discerning audible heartbeats. I was constantly digging for toki in the gardens, baffled by an almost total absence of Māori on land I knew they had claim to.

The concerns of the Pevensie children – sensible Peter, kind Susan, morally fragile Edmund and dear Lucy – felt similar to my own. An empty old house with an absence of parents; strange surroundings entirely different to those we knew as home; political upheaval on the edge of our consciousnesses; and the ever-present suggestion of a saviour as good as he was mighty, but hard to get in touch with.

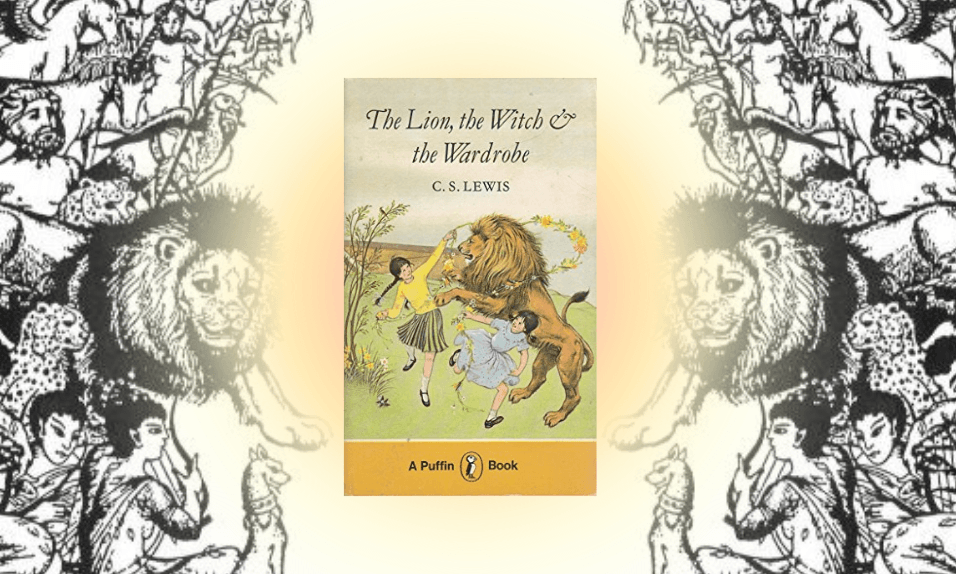

None of these correlations were suggested by the cover of the 1979 Puffin edition of the book I had – featuring a colour Pauline Baynes image of two old-fashioned looking girls dandling a flower garland around a dancing lion. It was an image so incongruous I could not – even though I’d spent time in Wonderland, Neverland and Oz – imagine a way into it. Perhaps if I’d known that the wardrobe had a looking glass on its door – and Lewis Carroll had shown me how cool they could be – I would have travelled beyond Spare Oom and War Drobe earlier. I needed a good dose of boredom, which came one day in the form of a sickness that saw me confined to my bed. Sneaking out of my room in search of relief, I felt like I’d read every book on those hallway shelves, except this old volume – its titular elements a puzzle unsolved. That was the day my adventures in Narnia began.

The 1979 Puffin edition of the book, with the Pauline Baynes illustration.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe reeled me in with appeals to the senses. Aurally, I was comforted by the whir of Mrs Badger’s sewing machine; and thrilled by the jingling of Santa Claus’s sleigh bells. My tastebuds were petitioned: while Edmund’s relatable Turkish delight compulsion clearly came to no good, the welcoming meals prepared by Mr Tumnus (on Lucy’s first visit to Narnia), and the Badgers (when all the siblings arrive) were all about security, delight and nourishment – particularly potent to children from a time of rationing.

I understood the solace of food, the routine of shared meals, and the importance of a judiciously meted out supply of cheap candy. Although I didn’t realise it at the time, running a household of six on one income required a certain amount of rationing in our house too. Stewed rhubarb from the garden, apples for snacks, a packet of Sparkles each a week, treat dinners of “hot bread” and Sally Lunn buns, and the routine of endless cups of tea (milky and sweet by degrees reflecting the drinkers’ ages) may not have ticked many nutritional boxes, but wove a spell of empty calories around us that spoke of a break from striving, tickled our tastebuds, and bumped our hunger up the track. My own hunger was always always threatening – the family-size tins we shared apparently made for a smaller family – and I related to both Edmund’s desire to gorge himself silly, and the Badgers’ understanding of food as fuel and comfort.

The main sense transmitted is that of wonder. Not only is the aesthetic world of Narnia amazing – with its talking animals, and host of mythological creatures – but its history is highly evolved, fantastical and dangerous. All of these elements are present in its blazing hero, the mighty lion Aslan.

Aslan spends a lot of time off-set, but I was already in love with this velvet-pawed wanderer long before I first encountered him. Lewis ensures that the reader’s trust could not be placed in a more noble being. In the book’s most harrowing moments – my own copy’s relevant pages tearstained; Baynes’ definitive, ink-black illustration tattooed on my psyche – Aslan gives his life for Edmund. Long, horribly dark hours later, triumphant, he is resurrected from the dead. It’s easy to recognise the Christian symbolism many believe Lewis — a renowned Christian apologist — worked into the text.

Pauline Baynes’ black and white illustration of Aslan and Narnian friends.

Although raised as a Protestant, Lewis – whose young life was far from easy – was an atheist by the age of 15. He addressed his return to faith at age 33 in Surprised by Joy: the Shape of My Early Life (1955). How this informed Aslan’s position in Narnia has seeded much discussion both for and against the book being used as a religious tool. As familiar as I was with our full-colour Family Bible as a child – with its terrifying plates of scenes like the one of Jesus casting Satan down the stairway to Heaven – none of this occurred to me until many years later. I read the books to myself, and discussed them with no one. It is generally agreed that this youthful naïveté was as Lewis would have wanted it. The twist in his intention was the suggestion it might make it easier for children to accept Christianity if they encountered it in later life. But Lewis did not intentionally set out to convert anyone to anything when he first allowed his pen to follow an image – of a faun carrying an umbrella and some parcels, in a snowy wood – his youthful mind’s eye had carried forward decades, into later adulthood. I see the tale Mr Tumnus led him to as one of the many overlapping stories through time (including that of Jesus Christ) in which Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey plays out – same, different, cyclic, monomythical.

The story has changed over multiple screen adaptations. The American animation released in 1979 is a simplification of the text. While the novel clearly portrays the children as evacuees staying at the home of a kindly Professor during World War II, the cartoon concentrates firmly on the fantasy, and the clothing style of the children suggests a 1970s setting. This two-part telemovie was widely peddled around the world, variously dubbed. In a pre-VCR-time of just two television channels, it was regular holiday programming I came to look forward to on a strictly limited viewing menu. Stripped of its nuance, the film bounced you through the narrative with little concern for subtext. Nevertheless, a persistently troubling echo of our old Family Bible Devil could be found in jittery Mr Tumnus – painted red as tomato sauce, faun horns poking through a green afro. I couldn’t help but wonder, had his gullibility somehow rendered him morally suspect? Torn between my own notions of right and wrong, could my own?

A serialised television programme of the book was released by the BBC in 1988 – again glossing over the evacuation details. I was a teenager by then, and did not form a strong connection with the show, and the ensuing series dramatisations (including the most recent Walt Disney / Walden Media films released from 2005). I’d developed an aversion to seeing what I now saw as my sacred text tampered with. I didn’t want to see it through anyone else’s eyes, or hear it in any other accents than the one I read it to myself in.

My love for the print version of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was growing as I did. My diaries liken the boy I fell in love with to the lion I’d loved for years, often by name. One entry in the form of a letter never sent – dated “1.03am, 23.10.89” – signs off: “By candlelight, goodnight, and I Love You Aslan.” (I was definitely not writing to the lion.)

I left home aged 17, but did not put away childish things. Although earning a pittance in retail, one of my first essential home purchases (paid off on laybuy) was the 1980 Lions London box set of The Chronicles of Narnia, with cover illustrations by Stephen Lavis. The volumes are worn in heaviest order from first to fifth (if you count The Magician’s Nephew as number one instead of number six – or number two which is the order I always read it in). I estimate I’ve read this copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (which this set numbers – chronological style – as number two) 10 times.

Bee Trudgeon’s Narnia book shrine.

In 2003 a heavy paperback, HarperCollins (2001) bind-up volume of the complete chronicles entered my grown-up house by way of a gift to my first child. With its fiery depiction of Aslan’s face on a shiny black cover, this was the edition I would read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe aloud from to my own children, putting it twice more into my own personal tally. I’m averaging a re-read of once every four years.

A slew of literary and religious examinations of the books have joined the original texts in my mind as I’ve grown older – into a parent and a children’s librarian – and become accustomed to casting a discerning eye over much of what passes through my hands en route to the hands of newer readers. Light has also shone through my consumption of Lewis’s writing for adults, casting new colours on the page of my enduring childhood favourite. While there have been times when I’ve questioned it – as some might their personal faith – I have never abandoned it, and it has remained a source of mystical pleasure for me.

Now Barbie mama Greta Gerwig is set to adapt and direct two Narnia films for Netflix. She has spoken about the theological roots woven into her work before, so I expect more of that in a realm rather suited to such musings. As for which two films she’ll tackle, a lot is still under wraps, and there is an arc left open by the Disney/Walden iterations begging to be closed. Although IMDB’s placeholder states only “Narnia (2026)”, with Meryl Streep thrillingly “rumoured” as Aslan, the hottest word is that The Magician’s Nephew (book one, two, or six – depending which camp you pitch your tent in) will be the first to see the light. Given that title is my second most-read Chronicles book, I’m excited to return to the place where the lamp post marking the boundary between our world and Narnia first grew.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by CS Lewis (and the other books in the series) can be purchased at Unity Books.