When the credit card statement of Rama Gupta (name changed on request) showed Rs. 7 lakh in unexplained transactions one September morning in 2023, she assumed it was a scam. The IT (information technology) professional from Andhra Pradesh had been struggling to care for her daughter with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) while managing rising household debts. What she discovered was even more alarming: her husband had cracked her phone’s password and had been draining her credit limit to feed his gambling addiction.

Today, Gupta, 38, is saddled with over Rs.1 crore in debt, entirely in her name, yet none of her choosing. She is among the hidden casualties of India’s Real Money Gaming (RMG) boom, where spouses, parents, and families become unwilling victims of addictions that can spiral from Rs.100 daily bets to crippling debt within months.

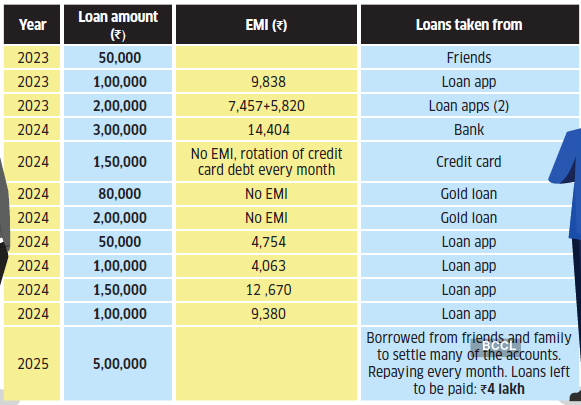

In Delhi, 27-year-old Ravi Kumar (name changed on request) squandered Rs.18 lakh in just 12 months on platforms like Stake, Mahadev, and Dream11. His journey from earning Rs.40,000 a month as an insurance employee to shouldering 12 different loans shows how quickly recreational gaming can spiral into financial ruin. “I kept convincing myself that another win would fix everything,” Kumar says. The big win never came.

Their stories are part of a staggering national crisis. As per industry estimates, 45 crore Indians have lost over Rs.20,000 crore on online RMG platforms. These losses have triggered a cascade of consequences, from domestic violence to suicide threats, ultimately prompting government intervention.

The Central government’s recent ban on RMGs seeks to slam shut a digital Pandora’s box, but for thousands of debt-ridden families, the damage is done. Behind the colourful interfaces, dopamine-triggering sound effects, and promises of easy money lies a carefully engineered system designed to keep players betting until they lose all. Here is a look at how games built to last minutes created debts that linger for years—and the desperate scramble to break free.

Descent into debtGupta’s nightmare didn’t start with that September credit card statement. It began a couple of years earlier, with small requests for money from her husband, who, despite having a regular job, never contributed financially to running the household. He first started playing online games around 2018 using his own money. When Covid-19 set in 2020, his firm’s activity dropped substantially, and he found himself at home most of the time: that’s when his addiction to online gaming took root. He first began borrowing from his friends, and then from his wife. What started off with Rs.5,000-10,000 at a time soon escalated to Gupta’s husband taking nearly 70% of her monthly salary. He cited Covid-induced unemployment and his parents’ medical expenses as excuses. She later discovered he had been gambling away the money or spending it on his family’s lavish lifestyle in their hometown.

ROMIL MEHTA, LEGAL COUNSEL

Note:“If someone is deeply in debt, recovery is difficult. Remember, sometimes you win, but mostly you learn.”

As her husband sank deeper into online gambling, Gupta’s life took a turn for the worse in 2022: she had unknowingly drained most of her savings to fund his addiction. He then coerced her to take a Rs.10 lakh loan on his behalf, claiming he needed it to repay debts from his parents’ hospitalisation during the lockdown, and emotionally blackmailed her with warnings of creditors at their door. Six months later, he cajoled his wife into yet another Rs.10 lakh loan for him. She still didn’t know about his gambling addiction; he would leave during the day on the pretext of taking care of his parents, who lived elsewhere, and would return at night. “I realised much later that he would come to me only for the money,” Gupta told ET Wealth over a phone call.

Ravi Kumar, 27

Addicted to online gaming.

Salary at the time of addiction: Rs.40,000

Gaming apps used: Stake, Cricbet, Mahadev, Zupee, My11Circle, Dream 11

Debt remaining: Rs.4 lakh

Squandered on gaming: Rs.18 lakh

Total debt:Rs.19 lakh approximately.

Loans taken from: Friends, banks, loan apps, family, gold loans

The lure of fast lifestyle upgrades drew Kumar to online gaming.

She finally found out about her husband’s online gaming addiction in 2023. He mostly gambled on Dafabet, a Philippines-based gaming app. Apart from repeated arguments and even physical assaults when she resisted, he would use emotional manipulation to bully her into taking loans from banks, fintech firms, and other lenders. Between 2022 and 2023, under pressure from her husband, she took Rs.30 lakh of loans, clinging to his hollow assurances that he would change. All this while, her conniving husband had been exploiting his job at a loan processing centre to rig the system and divert her loan applications to himself. This was apart from the gold her in-laws took from her after forcing her out of the house in 2020, just two years into the marriage.

The couple eventually separated, and the husband is yet to recover from his gambling habit. Despite settling loans worth Rs.30 lakh, she still had Rs.1.07 crore across six different loans. Of this amount, nearly Rs.95 lakh remains outstanding. Against a monthly salary of Rs.1.9 lakh, her equated monthly instalment is Rs.2.8 lakh. “My savings have been wiped out. Since all the loans are in my name, I have to clear the debt somehow,” says the distraught wife, who spends nearly Rs.1 lakh every six months for her daughter’s medical treatment. She says she might have to borrow from her family to repay her debts.

Dreams to dustGaming evolved from simple entertainment— 1980s handhelds, console cartridges, and mobile games like Snake—to sophisticated psychological manipulation. The final shift came with RMGs in 2019-20, which weaponised engagement techniques to extract money; the Covid lockdown accelerated this evolution.

Experts say that the government’s ban on RMGs appears well thought out, neatly bypassing the long-standing chance-versusskill debate. “Banning RMGs was necessary before more players lost money. It’s commendable that the government has chosen to uphold moral standards over chasing tax revenues,” says Romil Mehta, legal counsel at a video game company.

An August 2025 Angel One report says that the RMG sector contributes Rs.20,000-25,000 crore annually in direct and indirect taxes. But Mehta argues that RMG is highly addictive. “The more you win, the more you want to play; chasing losses is the quickest way to lose even more.”

Delhi-based Kumar knows this all too well. Swayed by the flashy lifestyles of his colleagues and friends, he craved more from life, and fast. A salary of Rs.40,000 a month in his mid-twenties wasn’t enough. What started with small bets of `100 a day on betting apps and Rs.2,000 per bet, not long after that, Kumar’s entire salary and his savings, which had accumulated to Rs.70,000-80,000, disappeared in a flash. “It was a thrill, a quick escape from reality, and for a while, it felt like the key to the lifestyle I craved,” he says. The wins were fleeting, the losses were devastating.

The one-more-win mindset spiralled into a vicious cycle, where he kept on losing money to the tune of Rs.40,000-50,000. More debts led to more loans, and more EMIs. To repay those, he played more, and sadly, kept losing. Eventually, when loan recovery agents came to his doorstep and threatened him and his family, Kumar realised things had gone too far. Driven by his desire for gaming, he had borrowed close to Rs.20 lakh across 12 loans, from banks, a loan app, and had also pledged his family’s gold. He is yet to repay Rs.4 lakh; the rest has been settled.

Bells and whistlesAside from the greed to make more money, why do gamers feel addicted to online games? This is because online games use a mix of bright colours, attractive designs and visual appeal to keep the players engaged. Farhan, a game developer and a recent computer science graduate, says that a game’s primary goal is to keep the player engaged and not make him leave. The way to do that is by triggering the release of dopamine, a brain chemical that creates a sense of reward and pleasure. Farhan explains that elaborate visual and audio feedback is everything in RMGs. Instead of a simple ‘Congratulations, you won’ pop-ups, these platforms bombard players with trumpets blaring, confetti exploding across screens, cash register sounds, coin-falling animations, phone vibrations, and multiple congratulatory messages, all designed to make even small wins feel monumental. “As a player, you feel, ‘Oh wow, I just did something big. I want to do it again’,” he says. This psychological manipulation through “bells and whistles” keeps players engaged even when they are losing money, because their brains associate the sensory overload with massive success. “The game has to feel rewarding even if you are not actually doing anything,” he adds.

How the debt trap works

As EMIs went up and losses mounted, Ravi Kumar continued to borrow money.

That’s not all. Like many e-commerce websites, online gaming sites also deploy psychological tricks, more commonly referred to as dark patterns, in the digital world. These are deceptive web designs that online websites use to manipulate users into doing things they might not do otherwise. They aim to manipulate your behaviour.

“The apps were designed to keep me hooked. They’d give small wins to keep my hope alive, but whenever I tried to withdraw a significant amount, my bets would fail. When I’d stop playing, a notification would pop-up: ‘Mr X just won Rs.12 lakh on the same bet you considered.’ It were such psychological tricks, making me believe I was just minutes away from a huge win, that kept me addicted,” says Kumar. Farhan adds that many gaming apps allow you to start a new game at the click of a button. But if you want to exit and take your wins off the table, “they make you go through multiple buttons and use colour tricks to keep the exit button away from your gaze.”

Stuck in debtDebt counsellors say that in the absence of individual bankruptcy laws, people must repay their loans. But more than repaying the loans, it’s the harassment that takes a toll. “Our first goal is to get the banks and lenders stop the recovery agents from chasing the debtors,” says Ritesh Srivastava, Founder and CEO, FREED.

Once threatening calls stop, debt counsellors focus on settlement strategies. FREED sets up escrow accounts where debtors set aside monthly amounts in professionally managed trusts. A Delhi-based debt counselling firm deploys around 100 advocates who communicate with banks, respond to legal notices and help ward off recovery agents. Once loans remain unpaid for 90 days and turn into Non-Performing Assets (NPAs), banks often realise that settling is better than selling them to asset reconstruction companies for a pittance. “We work with debtors to build solid evidence of their inability to repay. When you take the legal route to prove this, banks eventually listen,” says a debt counsellor who did not want to be named.

“In the US, nearly 7-9% of debt enrolled comes purely from gambling and betting, which is a regulated industry there. Until the RMG ban, India was showing similar patterns, only without the safety nets.”

RITESH SRIVASTAVA

FOUNDER AND CEO,FREED

Both Srivastava and Mehta say distress calls from people who’ve lost in RMGs have steadily increased. “The problem is serious, and many players do not realise their situation until they lose big amounts. There are stories of players begging customer support to return lost money, threatening selfharm, or losing their savings meant for children’s education and marriage,” says Mehta.

Rama Gupta, 38

Victim of husband’s online gaming addiction.

Loans taken: Rs.1.07 crore

Betting app: Dafabet

Debt remaining: Rs.95 lakh

Income: Rs.1.9 lakh monthly

Loans paid of: Rs.12.56 lakh

Gupta took the loans on behalf of her husband, who was addicted to online gambling

Primary motive behind the loans was to clear debts that her husband had taken from friends and local dealers.

How to spot & stop addictionSrivastava says that a sudden spike in unidentified expenses can be a clue that something’s amiss. You should avoid dipping into long-term investments like the Employee’s Provident Fund (EPF), unless it’s an absolute emergency. If you are prepared to navigate the multiple hoops the EPFO requires to release funds, make sure it’s not out of desperation for the wrong reasons. Gupta put too much faith in her husband and didn’t mind giving him more than half of her salary. Unless it’s a one-off case and you are convinced of the rationale, avoid such transactions and favours, and seek help.