What a few months it’s been. War continues to rage in Europe and the Middle East, Labour are U-turning like they’ve suffered a stroke at the wheel and we’ve watched the US President say fu*k on live TV – it’s time for a holiday. Whether you’re spending it in Great Yarmouth or on the Dalmatian Coast, no summer getaway is complete without some decent reading material. That’s why we’ve corralled our staff and contributors to put together this reading list. Enjoy.

Robert Colvile, CapX Editor-in-Chief

Given the political situation, the book at the top of everyone’s reading list should be ‘Conservative Revolution’, an essay collection edited by me and my colleague Karl Williams which explains how Margaret Thatcher, Keith Joseph and their allies went about the task of saving first the Tory party and then the nation, not least by founding the Centre for Policy Studies (which in turn founded CapX).

But if you don’t want to try the book proclaimed by Jeremy Hunt and others as essential summer reading, there plenty of other options out there. Currently sitting in my bedside stack are ‘One Party After Another’, Michael Crick’s biography of the betting favourite to be our next Prime Minister; ‘The Strategists’ by Phillips Payson O’Brien, on the parallel lives of Hitler, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin; and ‘Apple in China’, Patrick McGee’s gripping account of how the alliance between Tim Cook and Xi Jinping remade the modern world.

And finally I’d always recommend ‘K Blows Top’ by Peter Carlson, about Kruschev’s tour of the US, which might just be the funniest book I’ve ever read.

.

Marc Sidwell, CapX Editor

I’ve just finished a lost classic of 1950s sci-fi, ‘The Long Tomorrow’ by Leigh Brackett, in which a US devastated by nuclear war has embraced a religious hostility to technology and growth. Sound familiar? The story follows a young man desperate to escape to the fabled ‘Bartorstown’, where you can just do things, a reminder that the battles of today are just the latest in a long series of fights against the odds.

If you’re looking for non-fiction summer reading inspiration, look no further than some of the books previewed on CapX in the last few months. Some of my favourites include Don Boudreaux and Phil Gramm’s new history of American capitalism, ‘The Triumph of Economic Freedom’, Ben Chu on the dangers of deglobalisation, Bijan Omrani on the place of Christianity in English identity, Jeremy Hunt defending Britain’s role in the world, and Theo Clarke breaking taboos by talking about her experience of birth trauma and the scandalous state of NHS maternity services. Or to celebrate Margaret Thatcher’s centenary year, alongside the CPS’s ‘Conservative Revolution’, why not try Iain Dale’s mythbusting new biography.

As I head off to Cornwall next month, I’ll be packing John Cassidy’s ‘Capitalism and its Critics’, as well as ‘Abundance’ by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. Hope springs eternal.

.

Joseph Dinnage, CapX Deputy Editor

On a holiday to Paris earlier this year, I got around to reading Michel Houellebecq’s ‘Submission’, which depicts the eventual Islamisation of France. Wonderfully written, great characters, grotesque descriptions of a depressed professor’s carnality and a poignant warning about sleepwalking into extreme demographic change – it’s definitely worth a read.

After Bijan Omrani wrote for CapX in April, I picked up a copy of his latest book ‘God is an Englishman’, exploring Christianity’s enduring legacy in an increasingly secular Britain. The only child of baby-boomer atheists, I didn’t grow up pious – in fact I know there are many who’d call me godless – but it’s impossible to both know the history of Britain and deny the profound influence of the church on how we live and the values many of us still share. If, like many I know on the young Right, you are flirting with high Anglicanism, you could do worse than to read this.

Of course, as is the case every summer, the best stuff I’ve read has been the opinion pieces published on this august website. From the economics of air conditioning to the migrant crisis of 1709, from Ted Heath’s arrogance to the recent growth in political violence, CapX has got you covered. To all of our contributors, readers and even the radical Left lunatics who have tried so hard to destroy this country, have a fantastic summer.

.

Tom Willerton-Gartside, CapX Intern

As the breakdown of our institutions becomes ever more apparent, I’ll be using the summer to re-read ‘The Meiji Restoration: Japan as a Global Nation’ and ‘The Mind of War: John Boyd and American Security’. The former offers a case study of national reinvention under profound structural and agential forces, whilst the latter is a timely reminder about the mindset necessary to challenge and replace conventional approaches.

To look ahead to what the next five years may look like, I’m reading Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. With the Alan Turing Institute in crisis, Nick Bostrom’s book – which warns of the dangers of misaligned AI incentives – is pertinent to the challenges faced eleven years later.

Perhaps the best book I’ve read recently, though, is Eric Berger’s ‘Liftoff’. Away from the noise around Musk in 2025, this analysis of SpaceX’s early days emphasises the demands and culture needed to build a successful institution, against the odds.

Each book, in its own way, is therefore about the collapse or construction of order. That feels like fitting company.

.

Alys Denby

Let’s be honest, Britain’s economy is heading for the abyss, there’s a war in Europe and we have a rubbish left-wing government paralysed by militant trade unions and its own loony backbenchers. Do yourself a favour and choose escapism this summer – who knows it could be your last chance.

I’ll be taking a Cormac McCarthy novel on holiday with me. His violent, post-apocalyptic worlds may not sound that relaxing, but his writing is so astonishing and its bleakness is a strangely uplifting reminder of how much beauty there is in life. Mick Heron’s ‘Slow Horses’ novels are a brilliant update on the spy genre – where the antagonist is often the sclerotic British state rather than, you know, actual terrorists. I re-read ‘Money’ by Martin Amis this year in preparation for an event discussing his legacy: hilarious and a great opportunity to plug this CapX article I wrote about what he meant to me. You can absolutely never go wrong with anything by PG Wodehouse.

.

William Atkinson

I thought of starting by suggesting ‘London Fields’ – the Martin Amis classic that I have just finished re-reading. But then I realised I had already dubbed it my book of the year in the 2023 CapX reading round-up, and even I’m not that lazy in reusing old articles. The editors may beg to differ.

Instead, I’d like to recommend Robert Blake’s magisterial ‘Disraeli’ – the finest book written about anything ever, according to my first tutor at university. Having read it while working on my thesis – ‘The Evolution of Benjamin Disraeli as a Tory Icon, 1918-1970’ – I took it up again following a visit to Hughenden, the former Prime Minister’s home. As an illustration of a political life, the process of self-actualisation, and the vagaries of High Victorian Politics, it is unparalleled. When I first read it, I was reduced to tears. Sometimes a young man can be too sensitive.

Otherwise, I can also recommend Tim Wigmore’s new history of Test cricket – a fine history of the finest sport – and the Inspector Morse books, which I began working my way through again a month or so ago. It’s always a pleasure to write these little suggestions. It always reminds me how badly read I really am. For that, and so much else, I am forever in CapX’s debt.

.

Kristian Niemietz

In a strange way, I enjoyed Gary Stevenson’s ‘The Trading Game‘, which is a ‘Gary Begins’-style origin story of the popular economics commentator who managed to almost single-handedly make the wealth tax a thing again. I don’t buy his economic arguments (see my book review here), but his description of the mad world of high-stakes finance is intriguing either way. There is not much economics in the book, so you can mostly read it as his personal memoirs. But then, Stevenson has built his entire public persona on his origin story, so in his case, you cannot really separate the memoirs from the economics.

Bryan Caplan’s ‘Build, Baby, Build‘ explains Yimby-economics in the form of… a comic book. Yes, I know. But it somehow works.

Mark Dredge’s ‘A Brief History of Lager‘ tells the story of how lager – a type of beer which, until about 150 years ago, was almost complete unheard of outside of German-speaking Europe – became the world’s default beer, with a global market share of around 90%. Dredge takes us on a tour through breweries, Bierkeller and beer festivals, and describes the beers he samples in a way that makes you want to try a few. What surprised me most was how late in the day lager took off in this country: until the mid-1960s, lager accounted for no more than 2% of the British beer market. The book inspired me to do my own research to reconstruct the story of how lager came to Britain.

.

David Goodhart

I have a fantasy of one day writing a play or screenplay about the Bretton Woods conference of 1944, which not only shaped the post-war western economies but was full of personal drama. Keynes, head of the British delegation, was thought to have died at one point. Harry Dexter White, his US opposite number, was a Soviet agent of some kind. The three weeks of the conference was drowning in alcohol and confusion. To keep my fantasy alive, I recently read Ed Conway’s 2014 book ‘The Summit’, which brilliantly captures the constructive chaos of those weeks as well as lucidly spelling out the complex economic arguments. It’s relevant today because if Keynes had got his way with his clearing union idea we would not now be facing the Trump tariffs.

I am the owner of a shepherd’s hut in Oxfordshire that looks out onto a field of Charolais cows. For that reason I’ve been engrossed by the 2017 book by Rosamund Young, ‘The Secret Life of Cows’. Cows, it turns out, vary enormously in personality, intelligence and temperament. They have friends, can be good or neglectful parents etc.

I am (slowly, it’s in German!) reading my friend Jochen Buchsteiner’s ‘Wir Ostpreussen’ about his Prussian grandparents who were driven from their estate in 1945 and his, sometimes comic, attempts to reconnect with the Poles who now live there. The many German families whose relatives were driven from their homes after the war can now look back, as Jochen does, without either revanchist sentiments or self-pity. It should be translated.

.

Maxwell Marlow

The summer recess is an excellent time to take stock of the chaos of the past six months, and to get cracking down on my mounting stock of books! Note to readers, I am mainly an audiobook user.

I’ve started off my summer reading with ‘Kaput: The End of the German Miracle‘, which explores in fascinating detail and gripping narrative, the crawling collapse of the German economy. The social democratic economic model has failed, and the story of heavy industry has come to an end as eco-zealotry and mad geopolitical decisions have reckoned.

I’ll also be working my way back through Alain Bertaud’s ‘Order Without Design’. Alain, a veteran master planner and economist, merges the study of both disciplines seamlessly. Drawing on his experience from across the world – Algeria, India, New York – he finds that cities and towns are best left to their own in planning how they grow, build, and reinvest. It’s a must read for YIMBYs, especially those of us on the centre-right.

Finally, when I return from my travels in the land of Wordsworth and the Lakes, I will probably play some video games. ‘Helldivers 2‘, by Arrowhead Games, makes a return (as I’ve not stopped playing it). Video games get a bad-rap in serious circles, but as one of the most popular games, it’s a great experience to kick-back with fellow wonks and expand Managed Democracy throughout the Galaxy.

.

Reem Ibrahim

I recently visited Antony Fisher’s family home. He founded the Institute of Economic Affairs in 1955, and had written extensively on the failures of the government’s economic policy, and the desperate need for radical reform. On this visit, his granddaughter gifted me a book he had written entitled ‘Must history repeat itself? A study of the lessons taught by the (repeated) failure and (occasional) success of government economic policy through the ages’.

Although it was originally published in 1974, the analysis of the contemporary economic disarray could have been written today. He points to Britain’s decline in ‘individual freedom’, ‘growth of group envy’, and the ‘disappearance of respect for individual self-reliance’. Most interestingly, though, the last chapter of the book outlines a 10-year plan for radical economic reform. He describes how public spending can be drastically cut, tax can be lowered and simplified, and economic growth can be unleashed. I wonder if Thatcher herself ever came across this book.

My second recommendation is ‘Why as a Muslim I Defend Liberty’ by Mustafa Akyol. I initially read this book when I was at university, but recently revisited it due to its increasing relevance in attempts to combat political Islam. The book outlines why, contrary to the views of many, Islam is absolutely compatible with a free society.

Akyol argues that liberty and Islam are compatible if Islam is understood as a voluntary faith and not a coercive legal system, as many Muslims already see it. He also argues that Islamic texts contain the seeds of freedom, and argues for the reinterpretation of Islamic law and politics under the Quranic maxim, ‘No compulsion in religion’.

.

James Ball

I don’t read nearly enough fiction, which means that my summer reads might look a little bit stodgy on the beach. But with that said, I thoroughly enjoyed reading Keach Hagey’s book ‘The Optimist: Sam Altman, OpenAI, and the Race to Invent the Future’. There have been a flurry of books about OpenAI and its founder, but this one manages to combine being an illuminating read on one of the men driving the AI revolution with being a genuine page-turner.

Elsewhere, I’ve enjoyed Wolfgang Münchau’s ‘Kaput: The End of the German Miracle’, partly as an antidote to endless articles wondering why Germany ‘does it better’, but also as something of a counterpart to recent books on the abundance agenda – which often raise the question ‘why isn’t everywhere doing this already’. Münchau’s book helps answer this question: momentum, culture and tradition, and political calculus all factor in – often against growth. It’s also delightfully short, so shouldn’t test anyone’s hand luggage too strenuously.

.

Matthew Bowles

Recently, I completed the second volume of Robert Caro’s masterwork, ‘The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Means of Ascent’. It highlights LBJ’s 1948 Senate race, where underhanded tactics, ambition, and money converged in one of the most controversial elections in American history. Caro captures Johnson as a relentless, often ruthless operator and reminds the reader that politics is rarely clean, and power is seldom won without cost.

On a different note, I have also thoroughly enjoyed ‘The Magus’ by John Fowles. It’s a fairly disorienting novel following a young teacher who’s drawn into a psychological labyrinth on a remote Greek Island. With its existential games, it’s less about plot than the unsettling sense that nothing (and no one) is ever quite what it seems.

On the top of my ‘to read’ pile is ‘Judgement at Tokyo’. It’s quite the tome and therefore not one for the commute, but supposedly is the landmark history of the trial of Japan’s leaders post-World War II.

.

Kitty Thompson

Amid Shadow Cabinet reshuffles and general Labour tomfoolery, I have just finished reading James Rebanks’ ‘The Place of Tides’. Never has the urge to hop on a plane and get far away from Westminster been as strong as hearing about Rebanks’ time spent with an eccentric old ‘duck lady’ on Fjærøy, an island in Norway’s Vega archipelago. Writing for CapX is certainly fun, but the prospect of collecting eider duck feathers fresh from the nest somehow seems more worthwhile at the moment, as we collectively watch the Conservative Party embark on its journey of self discovery.

Alas, one measly eiderdown pillow won’t pay the bills. So to keep doing so, I will stay on top of my conservative environmentalist game and once again dust off my copy of Roger Scruton’s ‘Green Philosophy’ to remind myself how I ended up in Westminster in the first place.

.

Eliot Wilson

I’d always thought that the 1922 Committee, that trades union-cum-drop-in centre for backbench Conservative MPs, was a potentially rich and delicious subject for a book. Lord Norton of Louth’s ‘The 1922 Committee: Power behind the scenes’ is meticulous, characteristically well-informed and useful, and anyone interested in how Westminster works should read it. But Norton’s scholarly mien perhaps held him back from excavating the gossipy side of the ’22; perhaps an unauthorised biography of the institution awaits. Nevertheless, an invaluable primer for anyone who sometimes confuse their Gervais Rentouls and their Derek Walker-Smiths.

‘Beyond The Thirty-Nine Steps: A Life of John Buchan’ by the subject’s granddaughter Ursula Buchan is enough to make anyone feel inadequate. JB was everywhere and did everything. Best known as a pioneering adventure novelist, he found time to be a barrister, an early member of Milner’s Kindergarten in South Africa, journalist, editor, historian, civil servant, Member of Parliament and governor general of Canada. And he was good at them all. If you can still look yourself in the mirror and not wonder what you’ve done with your life, Buchan’s intellectual drive, rigour and application should be an inspiration.

One exquisite recollection of a bygone era when print was still king was Graydon Carter’s memoirs, ‘When The Going Was Good’. Of course it’s arch and the names drop like confetti, but Carter edited Vanity Fair for a quarter of a century. His depiction of the Condé Nast empire at its height is joyful, and every absurdity feels immediate and alive.

.

Tom Jones

Despite my disdain for political biographies, I read Tom Baldwin’s Biography of Keir Starmer. I thought I’d benefit by learning of the manager behind the decline; when reading this you understand it’s more an approach than ideology, an attempt to reduce politics to a process which can be controlled or managed, rather than allowing it to exist as something which — deriving authority from the people – is as alive, unpredictable, unruly, troublesome, demanding and wayward as they are.

I also bought a complete copy of Plutarch’s ‘Lives’, and have been dipping in and out. But to become great man of the people such as Pericles, or a ruthless dictator like Sulla? It’s important to retain an air of mystery.

Whilst I don’t like political biographies, I do like military ones, and enjoyed Ronald Lewin’s ‘Slim the Standardbearer’. Slim’s fundamental problem was morale, which dogged the 14th Army since the fall of Singapore. Perhaps his true achievement was to prevent military disaster by winning a moral victory; ‘he did well in manoeuvring his divisions, but he did better in making them the partners of his spirit.’ A lesson there, perhaps, for a leader attempting to rebuild a shattered party after a crushing defeat.

Oh – and I still haven’t watched ‘Adolescence’.

.

Damian Pudner

The beach might not seem an obvious place to think about the collapse of monetary orthodoxy or the rise of intelligent arachnids, but bear with me.

First up, ‘Broken Money’ by Lyn Alden. This is one of the sharpest and most accessible accounts yet of how the post-Bretton Woods monetary order is unravelling. Alden is a rare voice, blending technical insight with narrative clarity. Her core argument – that the fiat era is buckling under the weight of politicised credit, currency debasement and central bank omnipotence – is compelling. You don’t need to share her enthusiasm for Bitcoin to be gripped by the force of her analysis. It’s essential reading for anyone still labouring under the illusion that monetary policy is neutral or technocratic.

For something completely different but just as illuminating, ‘Children of Time’ by Adrian Tchaikovsky is a brilliant and unsettling masterpiece of science fiction. A sweeping saga of evolution, collapse and the strange paths intelligence can take. It’s also the best novel about empire and unintended consequences that never once mentions politics. Also: spiders. Lots of spiders.

Lastly, ‘The Price of Time’ by Edward Chancellor. It starts as a leisurely history of interest rates but quickly builds momentum. Chancellor shows how central banks’ manipulation of money distorts investment, inflates bubbles and weakens the foundations of capitalism. The final chapters are especially strong, linking cheap money to inequality, financial instability and democratic decay. It’s ‘The Road to Serfdom’ for the QE era.

.

Bruce Anderson

Two outstanding history books have appeared this year, and neither author is attached to a university. So much the worse for our universities. ‘Allies at War’, by Tim Bouverie, charts the relationships between Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin. It is written with verve, vigour and insight. Roosevelt becomes progressively less likeable as the years go on, possibly because his health was beginning to fail. But there was an element of small-minded jealousy in his relations with Churchill. Churchill knew that he had to ally with Stalin, but Roosevelt seems to have convinced himself that he could tame the Soviet monster.

Despite Churchill’s unique importance and world-historical grandeur, there is an element of pathos as the years go on. The greatest war leader finds himself in the role of demandeur. Although he did not intend to preside over the dissolution of the British Empire, that was what the future held.

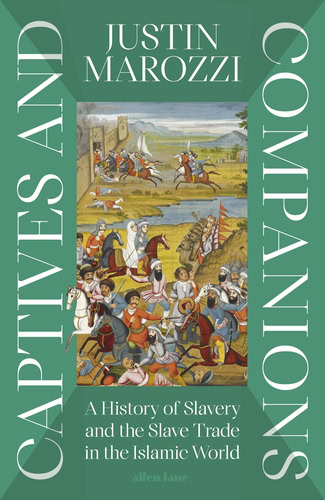

Apropos the former British Empire, Justin Marozzi has travelled extensively in much of it, especially the Middle East. ‘Captives and Companions, a History of Slavery in the Islamic World’ is an unfashionable subject but offers a fascinating account of those long centuries when slavery was so prevalent in the Islamic empires and nations. Again, unfashionably, the British come out well, as victims and suppressors.

Both these books are beautifully written, and would go well with whichever local wine is at hand.

.

– the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.