Food insecurity could lead to a higher risk of dementia and accelerated memory decline in older adults, new research found.

A shortage of food and persistent hunger increase a person’s risk of experiencing a range of health harms, including nutrient deficiencies, a weakened immune system, chronic diseases like obesity and osteoporosis, mental health issues and cognition problems.

A team of American and UK researchers analyzed data spanning about six to nine years from older adults without dementia or cognitive impairment at baseline.

The study found that food insecurity, measured when participants were around 67 years old on average, was significantly associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment.

However, food insecurity was much more strongly linked to cognitive impairment in people under 65 compared to those over 65.

Those without enough to eat were nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with cognitive impairment or dementia during the study’s follow-up period. Inadequate nutrition directly damages the brain, and the persistent fear of hunger keeps the body’s stress response chronically activated.

The researchers concluded that middle-aged adults between 50 and 65 may be the most critical group to help, as intervening early could prevent a debilitating neurological illness down the line.

Dementia develops gradually. Intervening to address their food insecurity at this earlier stage in life could potentially have the most significant impact on protecting their brain health and preventing dementia later on.

Research showed that food insecurity in older adults was linked to a higher risk of cognitive decline. This risk was particularly pronounced for those under the age of 65 (stock)

Your browser does not support iframes.

Food insecurity is a nationwide blight that affects 47million Americans at some point each year.

To understand the link between hunger and the mind, researchers from Harvard University, the University of Michigan, Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health turned to the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a database looking at aging in America.

They analyzed data from a group of 5,851 older adults aged 50 and above, with an average age of 67, for nearly nine years. These individuals showed no signs of memory problems at the study’s outset, which allowed researchers to track the development of cognitive issues over time.

At the study’s start, around nine percent of participants experienced low food security and seven percent had very low food security. Over 83 percent of them were food secure.

‘Low food security’ was defined as a score of two to four on the six-item Food Security Survey Module, indicating problems with affording balanced meals or anxiety about food supply, but typically with little or no reduction in food intake.

‘Very low food security’ is defined as a score of 5 to 6. This indicates more severe conditions where a person’s food intake is reduced and normal eating patterns are disrupted due to a lack of food.

Cognitive health was rigorously assessed through tests administered every two years, categorizing participants from normal aging to mild impairment to dementia.

The team then calculated the risk that food insecurity would lead to cognitive decline, while accounting for other factors such as wealth, education, and pre-existing health conditions, which allowed them to isolate the distinct role that hunger plays in disease onset.

They also specifically tested whether age made a difference, comparing the risks for adults under 65 to those who were older, to see if the impact of food insecurity varied across a person’s life.

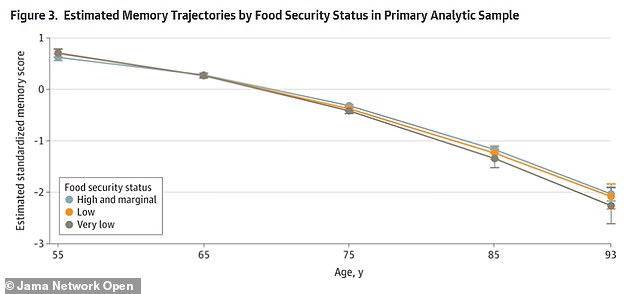

A previous study found that food insecurity accelerated cognitive aging. For those with very low food security, their memory decline was equivalent to an extra year of brain aging for every year of life

Over the follow-up period, the researchers observed a clear pattern. Compared to their food-secure peers, older adults who were food insecure saw a significantly higher risk of cognitive decline.

The study showed that those with low or very low food security were about 1.6 to 1.8 times more likely to develop neurological conditions, including mild cognitive impairment or dementia.

The most striking finding was that age had a dramatic influence on the risk.

The link between food insecurity and cognitive problems was stronger for adults under the age of 65, more than doubling their risk of dementia and other cognitive impairments.

In contrast, for adults over 65, the association was weaker and often not statistically significant.

The researchers wrote: ‘Stronger associations among older adults younger than 65 years suggest that this subgroup may gain greater cognitive benefits from interventions [between the ages of 50 and 65] targeting food insecurity.’

Previous research into the connection between food scarcity and cognitive decline has found that when older adults experience food insecurity, they experience more than just hunger and low blood sugar.

Studies show that when seniors struggle to afford food, they often end up with poorer diets, which can set the stage for a cascade of problems, from heart disease and diabetes to heightened stress, depression and a significantly increased risk of dementia.

Over a lifetime of food scarcity, the pathway often begins with a simple lack of money, which limits access to nutritious food, leading to a diet lacking in quality and variety, and ultimately triggering a domino effect.

Poor nutrition can directly harm brain health, while the constant anxiety of not having enough food can activate the body’s stress systems.

Together, limited access to whole, nutritious foods and chronic anxiety can worsen physical and mental health, creating a perfect storm that accelerates cognitive decline when people get older.

The researchers behind the latest study, published in JAMA Network Open, argued that their findings make the case for improving nutrition assistance programs for seniors, such as meals served in a group setting at a central location like a senior center, community center, or church, and bolstering the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps.

They said: ‘Our findings suggest that policies addressing food insecurity may reduce the risk of cognitive impairment among aging adults.’