It was the hit play that became a flop film, only to grow into a cult phenomenon. It was a homage to old horror films that became a celebration of queerness. And it only came about because in 1972 Richard O’Brien, having just become a father, got sacked from the cast of Jesus Christ Superstar, found himself in desperate need of money and work, and wrote a musical for the Royal Court Theatre in London to pocket the £200 writing fee. Now his son Linus O’Brien, 53, has made Strange Journey: The Story of Rocky Horror, a documentary that follows not just the 50-year journey of the play and film but that of his father too.

“I first saw the stage version of Rocky Horror when I was four, at the [long-gone Kings Road cinema] Essoldo,” Linus says. “The cast acted as usherettes, directing everyone to their seats while wearing these clear plastic masks, and I remember feeling it was ominous, threatening … and incredibly exciting.”

He is speaking from his apartment in downtown Los Angeles while his father joins from his home in Tauranga, New Zealand. In 2017 a bronze statue of Richard’s character, Riff Raff, the resentful servant of Tim Curry’s mad scientist Frank-N-Furter, was erected in Hamilton, the town where he grew up, about fifty miles from where he now lives. It’s a sign of just how far Rocky Horror has come, of its enduring influence against the odds. Fifty years after a critically and commercially disastrous initial outing, The Rocky Horror Picture Show has become the longest-running theatrical release in global history. Going to see the film in a cinema dressed as your favourite character, talking back at the screen and generally whooping it up is a rite of passage — particularly at Halloween — while its themes of sexual liberation have been embraced by the LGBT community. A 4K remastered version is screening at cinemas this autumn.

• Why we still love The Rocky Horror Show after 50 years

“My first reaction on seeing the documentary was relief,” says Richard, 83. “Companies all over the world had been approaching me about making one, but I was worried that they would come with an agenda. That’s why I was pleased when Linus said he wanted to do it.”

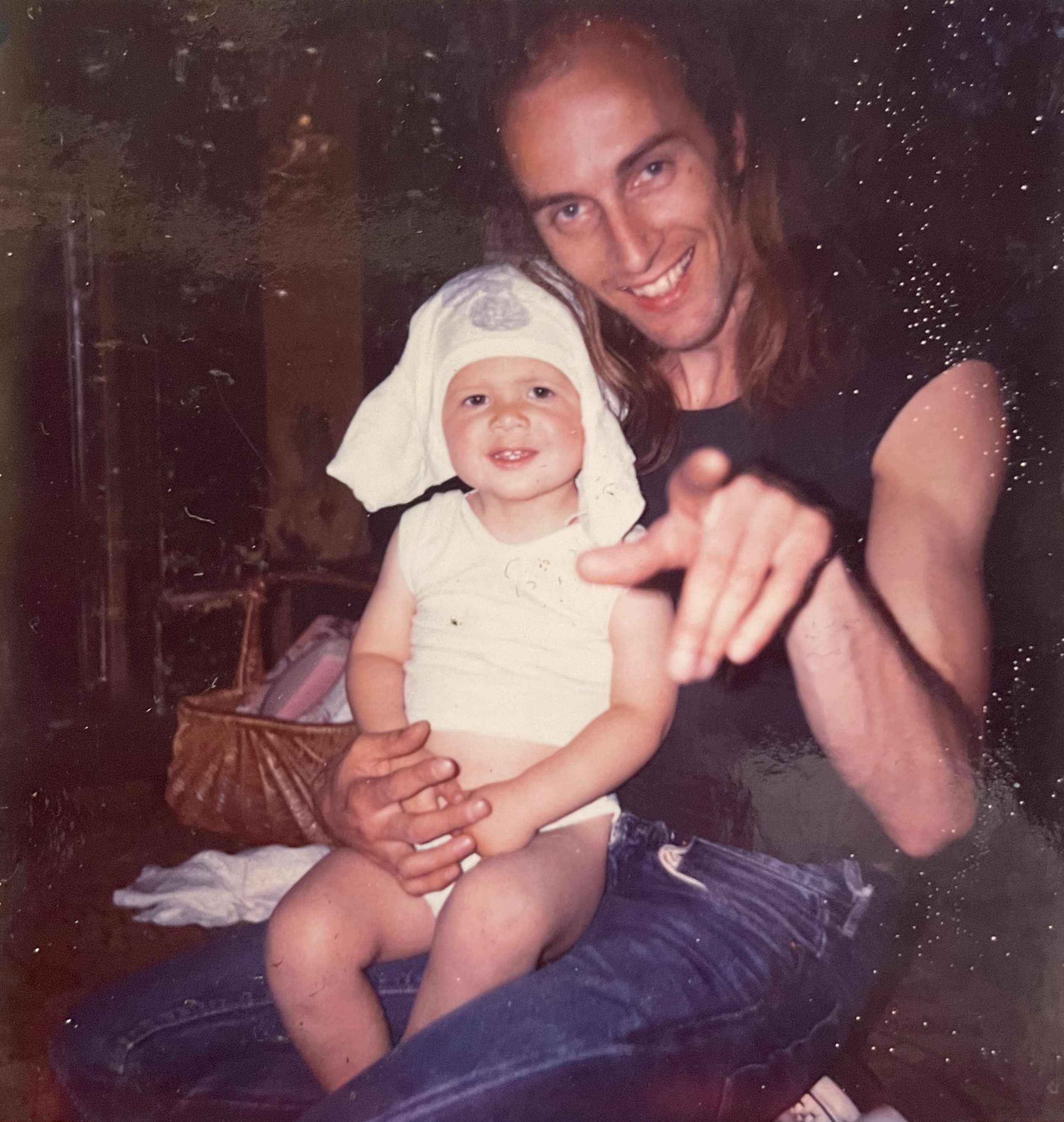

Richard O’Brien as Riff Raff with Quinn

MOVIE POSTER IMAGE ART/GETTY IMAGES

That agenda concerns Richard’s complex relationship with gender. Having felt conflicted about his sexuality since childhood, he now believes he is 70 per cent male, 30 per cent female. “None of us have asked to be born male or female, none of us asked to have blue eyes or brown eyes, and none of us have asked to be born straight or gay. It just happens,” Richard says. “When I was six and a half, I said to my brother that I wanted to be the fairy princess. The response made me bring down the shutters for decades.”

• Read more film reviews, guides about what to watch and interviews

I wonder if father and son talked about this when Linus was growing up. “All I knew is that there was a deep level of frustration in my dad until he could proclaim how he felt,” Linus says. “It was sad to see at times.”

“In a binary world, it’s a curse,” Richard confirms.

Linus O’Brien with his father sporting Riff Raff hair

Richard tackled the issue in Rocky Horror, albeit in a fun, campy way. It is the Adam and Eve story with a bit of Frankenstein thrown in: two innocents, Brad and Janet, enter an old dark house to be seduced by Frank-N-Furter, a metaphorical snake in fishnets and high heels, who is busy making the perfect muscle man after an earlier creation, a rock’n’roll biker played in the film by Meat Loaf, goes horribly wrong. Barry Bostwick’s Brad is the all-American male who ends up in an orgy in a swimming pool; Susan Sarandon’s Janet is the repressed good girl who discovers her freedom. As Sarandon says in the documentary, “Janet wants to be loyal to her idiot boyfriend while opening herself up to sexuality. I think the film is about saying yes.”

• Susan Sarandon: ‘I was dropped by my agent, my projects were pulled’

Before the film came the musical, a product of experimental theatre, the emerging gay rights movement and glam rock. Curry, Patricia Quinn (Magenta) and the costume designer Sue Blane first met at the Citizens Theatre in Glasgow, the groundbreaking centre of experimental theatre in Britain at the time. In 1971, Curry and Blane worked on an all-male production of Jean Genet’s The Maids at the Citizens. A year later, Blane got a call from Harriet Cruickshank, former manager of the Citizens, who had taken over the 63-seat Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court. Cruickshank had agreed to stage a production of The Rocky Horror Show with the Australian director Jim Sharman on board, but now there were only two weeks to pull the whole thing together.

Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon as Brad and Janet

20TH CENTURY FOX/SHUTTERSTOCK

“Harriet said she was desperate,” Blane remembers. “Jim Sharman was plaguing her to find a costume designer for this rather odd musical. An hour later, Jim, who had directed Richard O’Brien in Jesus Christ Superstar, arrived in a pair of white platform boots. That’s where it all began.” Blane brought a corset she had designed for The Maids to use for Frank-N-Furter’s outfit in Rocky Horror and put the whole look together on a very small budget.

The Royal Court had a tradition of high-minded experimentation, but Richard was a lover of B-movies, comic books and rock’n’roll. “With the exception of Little Nell Campbell [who plays Columbia], a tap-dancing busker who was working as Jim Sharman’s cleaner, we were all actors,” Richard says of the original team. “I had been to the Actors Workshop, but I was a lowbrow who thought entertainment was divine. The Royal Court was about muscular theatre, serious social issues. Yet the most famous production to have emerged from it is Rocky Horror.”

Richard O’Brien, far right, as Riff Raff with Campbell, Quinn and Curry

REX/SNAP/SHUTTERSTOCK

Rocky Horror opened on June 19, 1973, and was an instant hit. The record producer Jonathan King came on the second night, having read a glowing review by Jack Tinker in the Daily Mail, and offered to put out the soundtrack, which he recorded with the cast in a day and released two weeks later. In a review for Punch, Barry Humphries called Rocky Horror “impossible to overpraise”. London’s gay community embraced the musical, while Vincent Price, David Bowie, Rudolf Nureyev and Elliott Gould were among the stars who came to see what all the fuss was about.

Mick and Bianca Jagger attended what should have been the last night at the Royal Court, but the performance was cancelled because, according to Quinn, “Raynor Bourton [Rocky] was in agony after getting glitter under his foreskin. It was made of powdered glass in those days.”

Mick Jagger with Sue Mengers at a stage production of Rocky Horror in Los Angeles

FAIRCHILD ARCHIVE/PENSKE MEDIA/GETTY IMAGES

The record producer Lou Adler turned up to Rocky Horror at the behest of Britt Ekland, his girlfriend at the time, and immediately saw its potential. “The ambience, the usherettes, the outfits … It was an event,” Adler says. “I thought, this could run for a long time in LA. Maybe for ever.”

Adler duly staged the musical at the Roxy, a music venue on Sunset Strip, casting Meat Loaf as Eddie. Los Angeles audiences did indeed love the glam theatricality of it all, but New York was a different story. In 1975, the production moved to the august Belasco Theatre on 44th Street and bombed, not least because it was dismissed as a vulgar LA import. “New York sees itself as chic and LA as a tart,” Richard reasons. “They have the Met, after all.”

The real problems began with the film, which was shot in England. Adler had the good sense to use most of the play’s original cast and crew, which meant the Americans Bostwick and Sarandon were entering an unfamiliar, close-knit world, mirroring the experience of Brad and Janet. Everyone worked day and night because budget constraints made the three-week shoot at Bray Studios in Berkshire preposterously short, and after shooting the orgy scene in the swimming pool Bostwick and Sarandon became ill, getting little sympathy from the hardy Brits.

Richard now believes he is 70 per cent male, 30 per cent female

“Susan Sarandon has dined out on her pneumonia for 50 years,” Quinn says with exquisite dismissiveness. “If she mentions it again, I shall scream.” Quinn also had to deal with shooting the lip sequence that opens the film, miming to Science Fiction/Double Feature with her head clamped in a vice to stop it going out of frame. When her husband called in the middle of the shoot to ask for a divorce, she shouted, “Tell him I’m clamped!”

The film came out in 1975 and was a flop. There the story should have ended, but a year later The Rocky Horror Picture Show landed a midnight slot at the Waverly Theatre in New York, where a young actor called Sal Piro started the “shadow cast” phenomenon in which audience members would don make-up, fishnets and high heels, answer lines and generally become a part of the show. The cult of Rocky Horror was born.

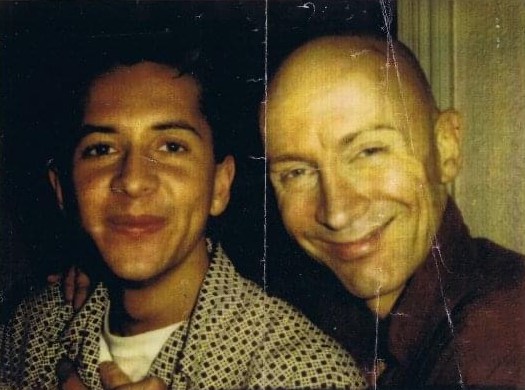

Linus O’Brien with his father, Richard

“My dad talks about how seeing the shadow cast with the film playing in the background created something altogether new,” Linus says. “It was a unique form of performance art.”

What, then, is the enduring appeal of Rocky Horror? “At least 50 per cent of it is the music,” Linus says. “At every screening, fans get to sing and dance together to their favourite album. Then you have Tim’s incredible performance. Throw in the Fifties B-movies, the sexual liberation and the sense of connection for people who have felt marginalised and you can see why it has become a phenomenon.”

“I suppose it’s: ‘Don’t dream it, be it,’ ” Richard concludes, quoting the film’s most famous line. “In Rocky Horror, there is no judgment on the way people look or the way they choose to live. It is a homage to the lowbrow, a hymn to the ordinary.”

Strange Journey: The Story of Rocky Horror is in cinemas on October 3

Two-for-one cinema tickets at Everyman

Times+ members can enjoy two-for-one cinema tickets at Everyman each Wednesday. Visit thetimes.com/timesplus to find out more

Which films have you enjoyed at the cinema recently? Let us know in the comments below and follow @timesculture to read the latest reviews