Walking through the John Carter Brown Library’s massive wooden doors, visitors may overlook the tiny, unassuming room that sits just inside the entrance. Taking a step in yields the scent of old books.

Nestled in the room is “Elemental: Crafting Books From Nature,” an exhibition that takes guests on a journey through the complex history of bookmaking, featuring books from the 15th to 18th centuries. The exhibition, which is open through December, is curated by José Montelongo, the library’s curator of Latin American books.

According to Montelongo, the books on display are infused with “elements of the mineral world, the world of plants and the animal kingdom.” On perusing the display cases and their respective plaques, visitors’ attention may be drawn to the varying textures and colorful accents adorning the books, as well as the goat, calf and sheep skin that bind them.

Montelongo told the story of John Carter Brown’s son, who took a Dutch poem to a Parisian binder to have the leather stamped with patterns and gold flourishes.

Courtesy of Rythum Vinoben

Making parchment from animal hides was once the “most economic” way of binding a book, Montelongo told The Herald. Typically, the animal skins “would be de-haired and degreased” with a curved knife before later being treated with lime, he explained.

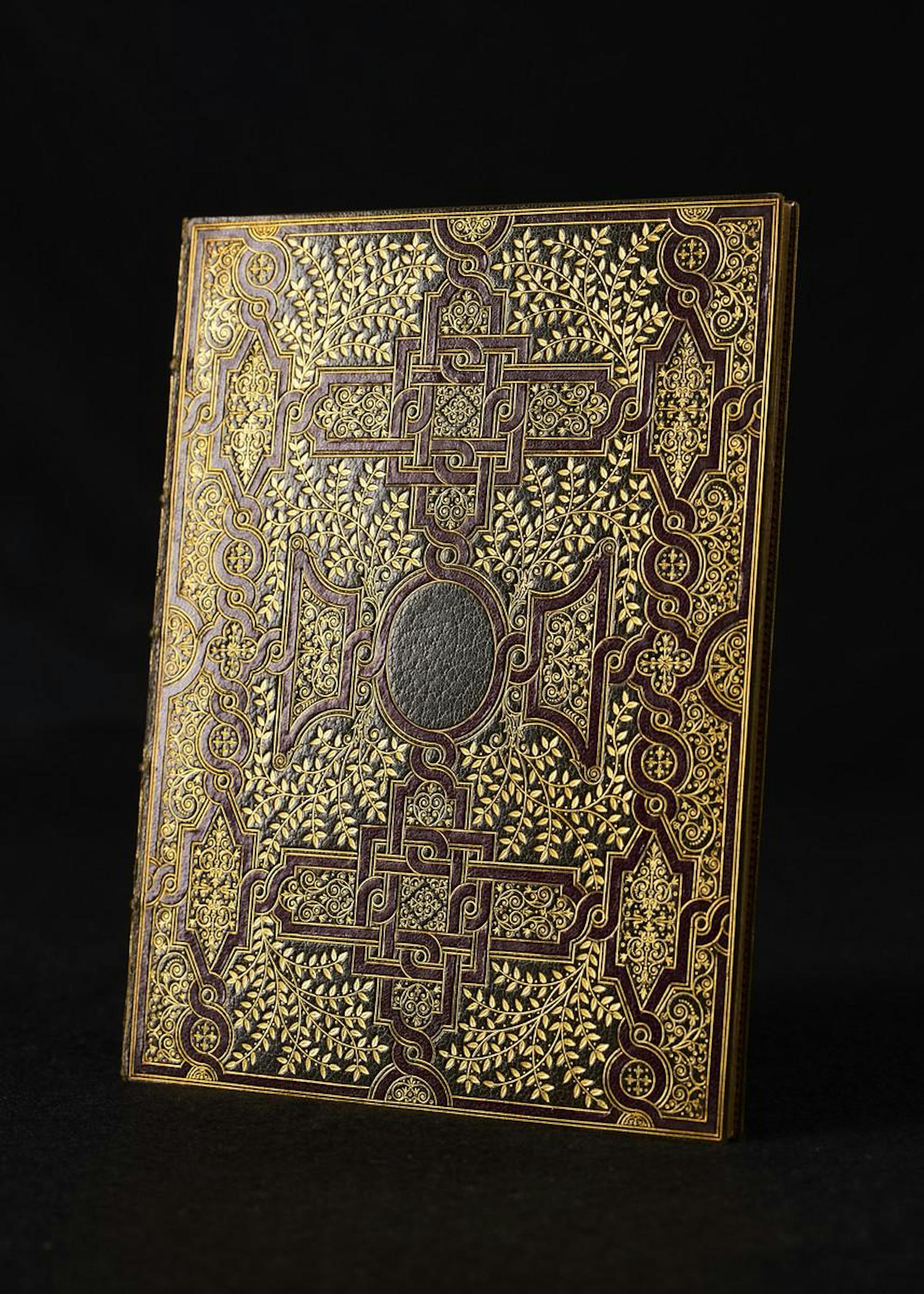

But other bookbinders preferred a more ornate approach. Pointing to a red leather book adorned with intricate gold detailing, Montelongo told the story of John Carter Brown’s son, who took a Dutch poem to a Parisian binder to have the leather stamped with patterns and gold flourishes.

Each book is accompanied by a detailed history of its making. “Margarita Philosophica,” a tome designed for young liberal arts scholars of the 16th century, is bound with strips of varying woods of unique colors and textures, a patchwork that Montelongo said most likely resulted from damage due to early libraries’ humidity, termites and “early intervention by a conservator.”

“Margarita Philosophica,” a tome designed for young liberal arts scholars of the 16th century, is bound with strips of varying woods of unique colors and textures, a patchwork that Montelongo said most likely resulted from damage due to early libraries’ humidity, termites and “early intervention by a conservator.”

Courtesy of Rythum Vinoben

Montelongo highlighted a large image on the wall depicting a prototypical printing office from the early 16th century. The image illustrates the messiness of the book-making process, with paper and inking pads strewn across the floor. Montelongo called it “the kitchen of bookmaking, not the bookstore.”

In the image, the office owner’s daughter is holding the printing type — or, as Montelongo puts it, “the elemental particle of bookmaking.” He described how the girl in the picture would take the movable type, made of an alloy of lead antimony and tin, and arrange an entire page “in the metallic state” before placing it on the printing press.

One of the books, however, isn’t bound at all. Montelongo noted the item’s “rare survival.” On the paper’s uneven surface, visitors can see the imprint of type from the other side of the page, a testament to “the force that (the bookmaker) is exerting,” Montelongo explained.

Some books, including one adorned with John Carter Brown’s own initials, were personalized.

Courtesy of Rythum Vinoben

He detailed the arduous process that went into making this paper by hand, calling it a “recycling enterprise.” Papermaking mills would repeatedly wash linen rags until the fibers became a pulp. Afterwards, they would separate the rags into smaller pieces using the force from running water before beating and molding them into a single sheet.

Some books, including one adorned with John Carter Brown’s own initials, are personalized. The exhibit’s themes of natural materials are echoed in the wooden and metal tools required to make these modifications.

Montelongo encouraged visitors to draw comparisons to their own book collections and recall how pages are worn through use and age. “The pages have been read, and it doesn’t stay the same, much less after centuries,” he said.

Get The Herald delivered to your inbox daily.