Indignity: A life Reimagined by Lea Ypi explores the period of transition between the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime in Albania through the lens of personal family history. The book began when Ypi came upon a photo of her grandparents honeymooning in the Alps in 1941 when she thought all such records had been destroyed. Below, read an extract from the book’s prologue about the discovery of the photograph and the unsettling questions it prompted for Ypi about the gaps in her understanding of her grandmother’s life.

Indignity: A Life Reimagined. Lea Ypi. Allen Lane. 2025.

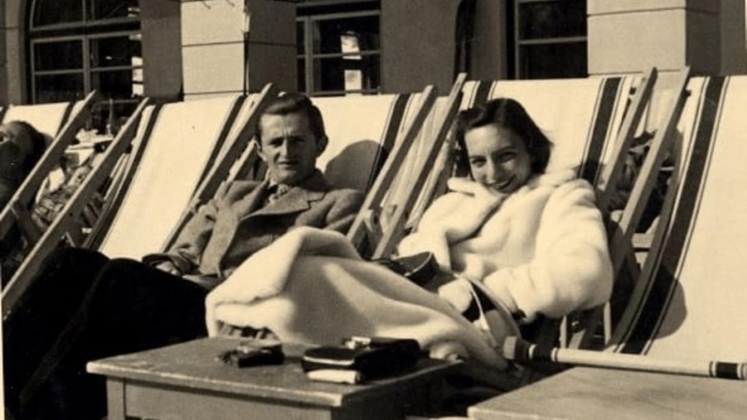

The photo, an old black-and-white image, was posted on social media by a man with the username Çim, probably short for a communist-era name such as Çlirim (Liberation) or Shkëlqim (Splendour) or merely Ndriçim (Enlightenment) – a person whom I had never met, or even heard of before. Within hours of being shared, it went viral across Albania. A young, glamorous couple stare at the camera, while relaxing on sun loungers in front of a luxury hotel. In the background a pair of skis leans against the wall, just under an arcade. The woman is clad in a long white fur coat, her hands buried deep in its pockets, a small handbag precariously balanced on her lap. Her big smile and vaguely distracted expression contrast with the much more serious, almost probing look of the man stretched out on the sun lounger next to hers. It’s hard to say if his frown and squinting eyes are on account of the sun or displeasure with the photographer, at whom he stares as if trying to communicate something. A packet of cigarettes lies on a nearby side table, and beneath it a paper carrier bag, fancy but not ostentatious. You can just about make out the name: ‘Hotel Vittoria’.

‘I felt the happiest person alive,’ she would say, ‘and Cortina was the happiest place in the world.’ Yes, truly, she would insist, even though this was Italy, and it was the winter of 1941 and war raged all over Europe as never before.

I did not need to read the caption online to recognize my grandparents, Leman and Asllan, in the photo. Judging by their winter attire, the name of the hotel and the skis in the background, it was taken during their honeymoon in Cortina d’Ampezzo, in the Italian Alps. The year was 1941. My grandmother spoke often and fondly of those ten days spent learning to ski in the Dolomites. ‘I felt the happiest person alive,’ she would say, ‘and Cortina was the happiest place in the world.’ Yes, truly, she would insist, even though this was Italy, and it was the winter of 1941 and war raged all over Europe as never before.

Years later, when she was no longer around, or perhaps because of it, I became absorbed by the question of what it meant to feel the happiest person alive in the winter of 1941. Part of me wondered if her description genuinely reflected her feelings at the time, and what this revealed about her character. I had trouble connecting her personal rendition of those weeks with my knowledge of historical events, both in Albania and elsewhere. Operation Barbarossa in the Soviet Union, the attack on Pearl Harbor, the ongoing battle in Yugoslavia, all this would have been making headlines just as she was learning to ski, relishing the crisp winter air. Was she indifferent to the most brutal battles of the most brutal war humanity had ever known? I had trouble squaring this with her personality, and with her views. She was no fascist apologist, of that I was certain. And she was far from indifferent to what was going on around her. Perhaps she was simply trying to cope, as she had done throughout her life, sensing that something even worse was about to unfold, that her days of innocence were numbered. Yet, her elaborate account of the young couple’s activities – skiing in the morning, bridge in the afternoon, dancing in the evening – was sufficiently focused on facts rather than subjective impressions to make me feel genuinely uneasy about sentiments that seemed at odds not simply with her character but with the entire trajectory of world events at the time.

The way she spoke about those days in Cortina clashed with my perception of her as a kind of moral saint – duty-bound, compassionate, always attentive to the needs of others before her own.

Looking back, after her death in 2006, I regretted having been unable to articulate clearly not so much these questions but what I found disturbing about her reconstruction of that period in her life. The way she spoke about those days in Cortina clashed with my perception of her as a kind of moral saint – duty-bound, compassionate, always attentive to the needs of others before her own. It is not that I had expected her to forgo her honeymoon – life continues, even in 1941, even in the middle of war, perhaps with greater intensity, the closer one feels to the end.

This excerpt from Indignity: A Life Reimagined by Lea Ypi published by Allen Lane (2025) is reproduced here with the permission of the author and publisher. © Lea Ypi 2025.

Note: This review gives the views of the author and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main image: A photograph of Lea Ypi’s grandparents, Leman and Asllan, in Cortina d’Ampezzo during they honeymoon in 1941.

Read a review of the book here.

Enjoyed this post? Subscribe to our newsletter for a round-up of the latest reviews sent straight to your inbox every other Tuesday.