NEED TO KNOW

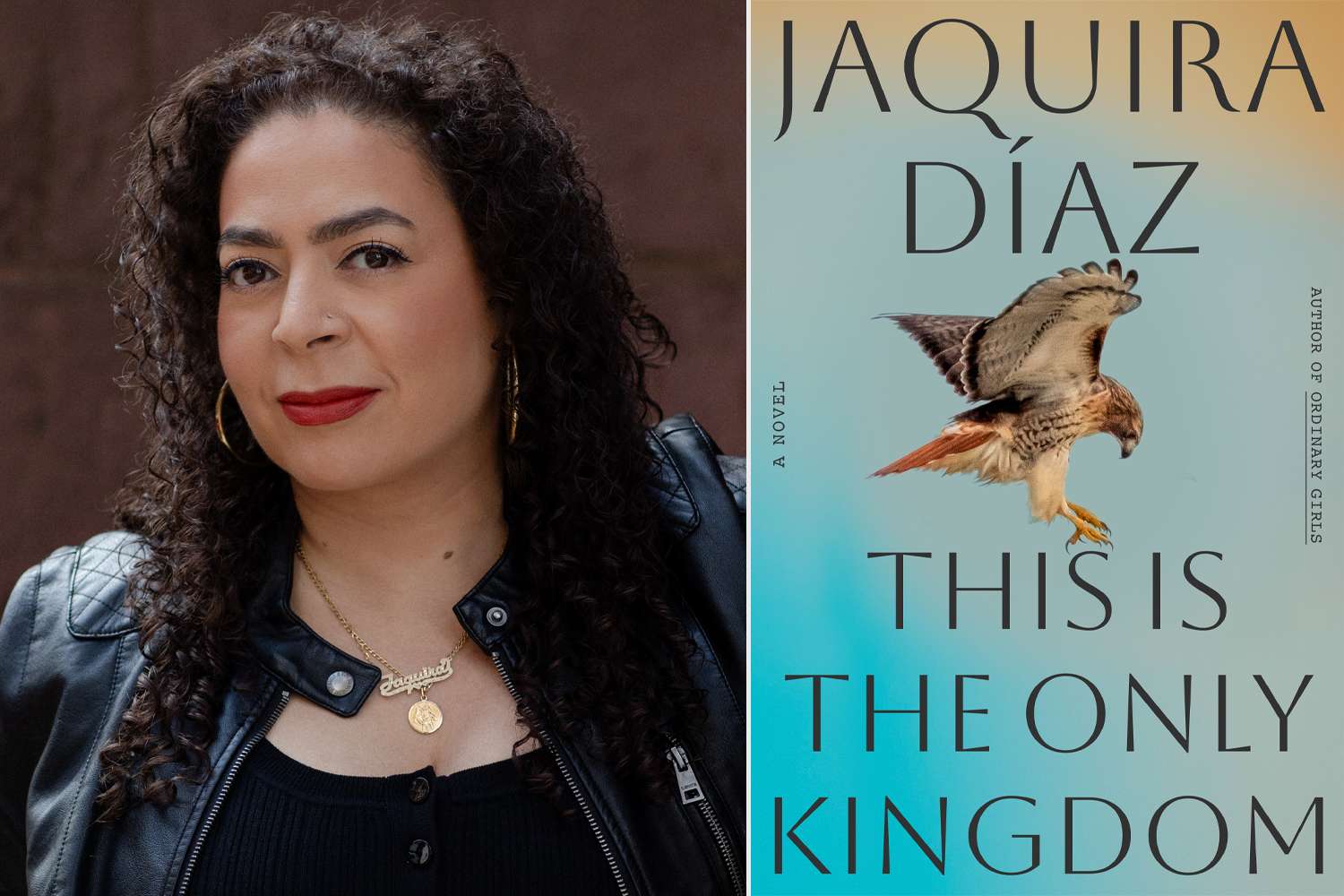

Whiting Award winner Jaquira Díaz has a debut novel on the way, This Is the Only Kingdom

The epic novel, which has already been longlisted for the Center For Fiction First Novel Award, follows a mother and daughter dealing with the fallout from a murder, set against the backdrop of a close-knit Puerto Rico barrio

Read an exclusive excerpt from the book below

After a few weeks, the cops stopped looking for Rey. They forgot about him or moved on to other guys, other cases. He started coming around again, joining Ismael and Cano on the basketball courts, then they’d walk over to Cano’s apartment for drinks. During those afternoons, they’d sit around Doña Matos’s kitchen table, shooting the shit, sometimes play cards.

One afternoon, Rey brought out the deck, but Cano wasn’t interested. He didn’t have the money. He told Rey and Ismael how he was supposed to finish his degree, but things had gotten hard. He had his part-time job at the library, but that wasn’t enough for tuition, for books. It would take him an extra year to finish. He didn’t feel like playing.

“Besides,” Cano said, “I don’t feel like losing my last two quarters to a kid.”

Rey laughed and left the deck on the table, sipping on his Kola Champagne.

“I’ve been writing songs,” Ismael said. He was trying to get his band together. Ismael was always trying to start a band, but nobody ever took him seriously.

“So you’re really doing it,” Cano said, just being nice. He knew that Ismael could play, but the band thing would never happen.

“I’m doing it,” Ismael said. “Watch. When I get famous, all you sorry fools will come running.”

“I could play with you, you know,” Rey said.

Ismael smiled, slapped him on the shoulder. “You can sing too.”

Nowadays, Rey wrote these ballads that he sang all over el Caserío, busting out in a falsetto whenever he saw a group of girls walking home from school, serenading the abuelas whenever he worked the register at Don Ojeda’s store, making the schoolgirls blush or giggle, the older women saying things like If only I was 30 years younger. Everybody called him Rey el Cantante.

“But you gotta stay out of trouble if we’re gonna make this happen.”

“Listen,” Cano said. “I don’t know if you two will get famous, but if you get some gigs, I have my van. It’s old, has no seats in the back, but it works. I can drive you.”

Ismael raised his glass. “It’s a deal, then. When we make it big, I’ll get some fucking custom congas and I’ll buy you whatever you want. Hell, I’ll pay your f—ing tuition.”

Jaquira Díaz.

Sylvie Rosokoff

Rey and Ismael practiced for months while they found other musicians for their band. Eventually, they had a guy on trumpet, a trombonist, a bassist, a guy on keyboards and Ismael’s cousin Edgar as the temporary lead singer until they found someone better. Rey and Ismael were always at practice, but some guys came and went with the hurricane season. They couldn’t find a good lead singer, and Rey didn’t want to sing. He was a drummer, no matter how much Ismael insisted he should sing.

“You sing,” Rey said every time Ismael brought it up. “This whole thing was your idea. It’s your band.”

“But you’re a singer,” Ismael said.

“I can sing, but I’m not a singer. I freeze up, man.”

“If you can sing all over the streets, you can sing onstage,” Ismael said.

Take PEOPLE with you! Subscribe to PEOPLE magazine to get the latest details on celebrity news, exclusive royal updates, how-it-happened true crime stories and more — right to your mailbox.

They managed to keep Edgar on vocals, Ismael and Rey and the rest of the band practicing like every day, five days a week, for months. But they had nothing to practice for, no gigs. Until Cano’s older brother, David the deacon, who’d moved into the Catholic parish in el pueblo as he prepared to be ordained, came home for a visit.

Doña Matos was so happy to have him home, so proud that her son would soon be a priest, she cooked all his favorite foods: mofongo con camarones, arroz con gandules, pernil, tembleque. It was just the three of them, but she made enough food for a party. That’s how Cano got the idea, then went to find Rey and Ismael at the basketball courts.

“A party for your brother?” Rey asked. “Is it his birthday?”

“Nah. He’s getting ordained. He’s going to be a priest.”

“They have parties for that?”

Ismael clapped his hands. “This is el Caserío, my man. We have parties for everything!”

Soon everybody was out in the street with whatever they could afford to bring. People called their friends down in Patagonia, who arrived ready for a party — everybody knew Doña Matos from the neighborhood or the hospital. And everybody knew her eldest son from church. David the deacon, the good one, called by God, destined to be a priest.

So Rey and Ismael and their band played their first gig, a spontaneous Catholic block party. Rey on timbales, Ismael on congas, Edgar on vocals. Ismael and Rey played like they were stars, all eyes on them. Nobody knew that, to them, this felt exactly like living a dream. They weren’t great, but they weren’t embarrassing either. They were boys, 19, 22, 23, with a little talent and a lot of guts, who decided they would do something nobody in el Caserío had ever thought they could do. And that night, the neighbors, their friends, everybody danced.

As Loli started dancing with Carmelo, Maricarmen went to get a drink. That was the first time she had a real conversation with Rey, who handed her a Medalla from a cooler and asked her name. He’d been watching her awhile. She’d noticed him while he played, younger than all the other musicians, dark skinned and baby faced, with dark fuzz over his upper lip (that maybe could someday be a mustache), and all those curls.

The PEOPLE Puzzler crossword is here! How quickly can you solve it? Play now!

“How long have you been playing?” she asked him.

He took a moment, then shrugged. “I don’t know. Always.”

“Always? You mean like your whole life?” Maricarmen asked.

“Something like that.”

“Did you take music lessons?”

“Yes and no,” he said. “I taught myself. My uncle’s a musician too. You know how sometimes there are things you can just do, and nobody has to teach you?”

“I guess.”

“I had a music teacher, but the lessons didn’t teach me anything I didn’t already know.”

Maricarmen studied his face. She’d taken a few music classes, a handful of voice lessons with Don Ojeda that she paid for with money she made cleaning apartments. She’d dreamed of being a singer once, like Lucecita Benítez, or Blanca Rosa Gil, or like La Lupe on the Myrta Silva show, hips swaying from side to side, singing “La Tirana,” beautiful and irreverent and free. But that had been a dream.

They kept talking while all their friends danced in the street. Loli and Carmelo didn’t skip a single song, while Cano and Ismael danced with all the neighborhood girls. Maricarmen occasionally cut in to twirl around with Loli, turning her this way and that way, then handing her off to Carmelo when she went to the cooler for another drink — an excuse to get back to Rey. Over by the cooler, Rey and the rest of the band, all of them drunk, were gathered around the last of the beer.

‘This Is The Only Kingdom’ by Jaquira Díaz.

Algonquin Books

Carmelo headed their way and everybody turned.

“Who’s that? Your bodyguard?” Rey asked. The guys exploded with laughter.

Carmelo didn’t say anything, just lit a cigarette. He was younger than the other guys, a quiet skinny boy who had exactly two friends: Maricarmen and Loli.

“That’s my pana, Carmelo,” Maricarmen said, and quickly changed the subject. “So you guys write your own songs?”

Ismael smiled, put his hand around Rey. “This guy right here. He writes most of them.” He smacked his friend’s chest lightly. “Rey el Cantante. Isn’t that what all the girls call you?”

“Rey? That’s you?” Loli asked. “I thought Rey el Cantante was supposed to be sexy.”

Rey covered his face with one hand but couldn’t stop laughing.

“Loli!” Maricarmen said, a little too loudly.

“That’s what all the girls around the neighborhood are saying,” Loli said.

They talked and talked, late into the night. Ismael told them about Rey coming home after two years in a work camp for juveniles, how he’d had a real hard life but finally got his shit together, and now there he was. There they all were. And one day, they’d be able to leave this place.

Nobody wanted to go home. They had turned the music down, but it was still playing. And when a song they liked came on, they all swayed a little, everybody waiting for something — anything — to happen. And then something did.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

Cano saw them first, put his empty can of Medalla on the ground.

“Hey, man. Here come los camarones,” he said to the group, and took a few steps back.

Everybody did the same. Spread out, put down their cans. Loli immediately started walking home, as if she hadn’t seen the cops at all. Her mother would be mad as hell if los camarones brought her home at 3 in the morning.

“Mari, come on,” Loli said, then kept walking.

But Maricarmen stayed behind.

All those years later, they would all remember this moment. How they stood there watching as the two cops strutted toward them, trampling the moriviví that covered their front lawns, one of them holding his club, ready to strike, the other reaching for his sidearm. How nobody moved, all of them frozen where they stood, where they had been their whole lives, where their families had lived since the beginning of the colonial project that bulldozed their ancestral homes and sent them off to live in the caseríos públicos all over Puerto Rico, places built for the poor.

Places for people like them, and their parents before them, and their children after. Maricarmen and Loli and their mother. Carmelo and his mother, Evelyn. Rey and Tito and their mother, Iris; and his tío Ojeda; and his dead father.

Rey’s friends, Ismael and Cano. David the deacon asleep in his room, and Doña Matos, his mother, already working her nursing shift at Ryder Memorial. Loli already inside the apartment, watching from the window as her mother slept. Their neighbors, their friends, their families. How they all let themselves believe that their homes, their bodies, were their own. That they had a right to dance and sing in the street, drink a beer.

Once, el Caserío Padre Rivera had been a place of fairy tales, promises of new beginnings and urban renewal. But it wasn’t long before they all understood that everybody else didn’t live with the American factories dumping waste into their drinking water, with black ash snowing over them a few months a year. They’d come to understand that nothing was random, everything was connected, everything was deliberate. That the violence of their neighborhood would always echo the violence los camarones brought with them.

Los camarones, who arrived late into the night, who caught Cano and Rey and Maricarmen and their friends as they laughed together a few steps from their front doors, a few feet from their beds. The cop who lifted his pistol, Officer Altieri, as they stood frozen in front of Cano’s building. Altieri, who told them all to put their hands in the air. Who jumped, startled, when Rey laughed nervously. Who brought down his gun on the side of Rey’s face, knocking him sideways onto the dirt. And as they all scrambled, reaching for Rey, as Maricarmen screamed, threw herself to the ground where Rey fell, holding him against her, all the other guys between Altieri and Rey, it was Cano who tried to reason with the cops, his hands still raised in the air.

“Hey, you know me, man,” Cano said to Altieri. “You know my mother. She’s a nurse at Ryder Memorial?” Cano waited for some sign that Altieri had heard him, his hands shaking uncontrollably.

“My brother’s a deacon. He’s going to be a priest. David. This party’s for him.”

Cano looked to the other cop, who’d stepped beside Altieri. He wasn’t sure what else to say.

“He’s just a kid, man,” Altieri’s partner said.

Slowly Altieri’s gun came down, turned toward the sidewalk, finger off the trigger.

Cano looked them both in the eyes, his hands held high, his knees locked. But Altieri was looking through him, down at the ground, where Maricarmen was pressing her hand to the side of Rey’s bleeding face, and Carmelo was pulling off his T-shirt, handing it over to her. Altieri was watching Maricarmen. Cano knew it. He didn’t need confirmation. Altieri had his eyes on her, this white girl among a group of Caserío kids — a group of Black boys — and all the man could see was the story he’d told himself about who they were. And Cano didn’t need anyone to tell him what that story was.

Excerpted from THIS IS THE ONLY KINGDOM copyright © 2025 by Jaquira Díaz. Used by permission of Algonquin Books, an imprint and division of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

This Is the Only Kingdom will hit shelves on Oct. 21 and is available for preorder now, wherever books are sold.