It’s no wonder that there are barriers in front of the paintings in the Courtauld Gallery’s new exhibition. Wayne Thiebaud’s luscious displays of iced cakes and slices of meringue-filled pies are gloriously, irresistibly lickable.

The wobble of custard, the coarse foam of piped whipped cream, the gloss of a sugar glaze – all are so persuasively rendered in buttery sweeps and flourishes. The more extravagantly painterly Thiebaud’s gestures are, the more deliciously eatable they become.

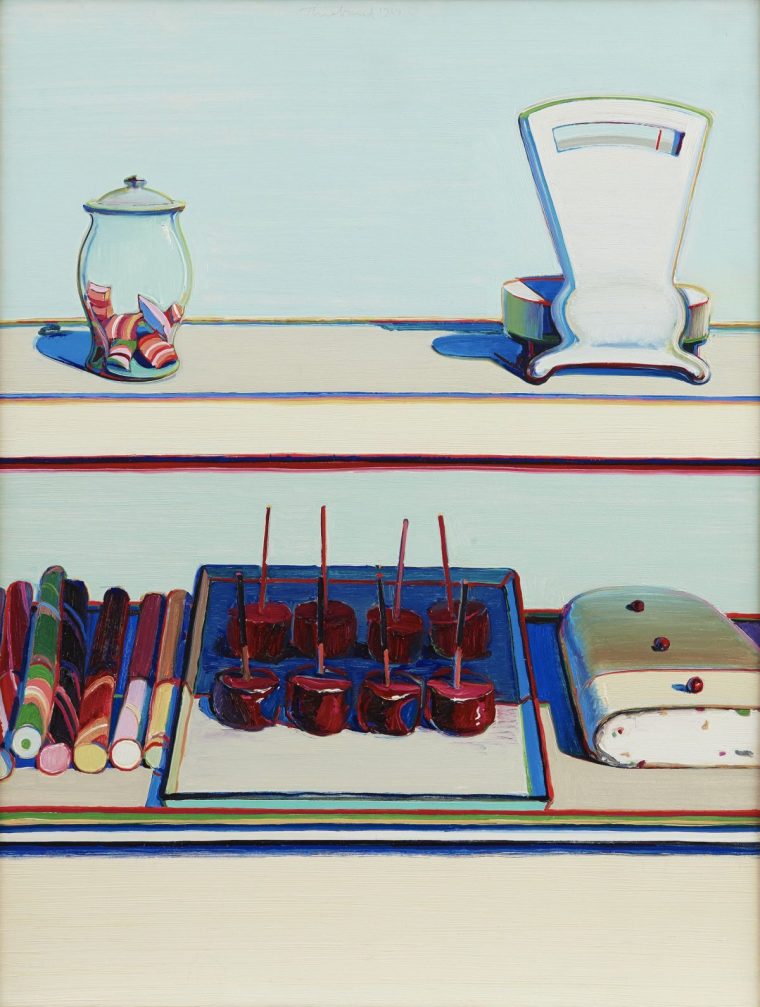

Candy Counter (1962) catalogues this topsy-turvy sensory world in the artificial colours of jaw-busting lollipops, the snap of toffee apple shells, and the yielding firmness of nougat waiting to be sliced. Thiebaud’s buttercream paintwork is not limited to the description of sugary treats, but extends across the canvas, so that the glass and metal counter, and even the cool blue wall behind are as luscious as a birthday cake. The set of scales and the lollipops on the counter top complete the effect, the paint around them pushed into a smooth ridge, just as if they were decorations pressed into fresh icing.

‘Candy Counter’ (1969) evokes the artificial colours of jaw-busting lollipops, the snap of toffee apple shells, and the yielding firmness of nougat (Photo: The Courtauld Gallery)

‘Candy Counter’ (1969) evokes the artificial colours of jaw-busting lollipops, the snap of toffee apple shells, and the yielding firmness of nougat (Photo: The Courtauld Gallery)

Born in 1920, Thiebaud lived in Sacramento, California, until his death in 2021, working as an illustrator and commercial art director whose expertise was in designing in-store displays. In the early 50s he turned to teaching, which gave him time to paint, and, as an artist who had himself learned on the job, he said “it was really my education”.

Thiebaud is celebrated in his native USA, but in Europe he’s much less well-known, and this is the first exhibition of his work to be staged in a UK museum. The Courtauld is a rare European custodian of Thiebaud’s work. Its recent acquisitions include Cake Slices (1963), the cue for American Still Life, and a companion exhibition of works on paper.

Thiebaud’s breakthrough came in 1961, when he shared his debut show in New York with another unknown artist, Andy Warhol. But though they share the lexicon of post-war mass production and American consumer culture, Thiebaud’s commitment to painting contradicts Pop Art’s cool cynicism, and its fascination with the printed images of advertising and the mass media.

‘Five Hot Dogs’ (1961). Thiebaud’s ‘multiples’ are superficially similar to Warhol’s, but his arrangements of seemingly identical items are marked by slight differences and imperfections (Photo: John Janca)

‘Five Hot Dogs’ (1961). Thiebaud’s ‘multiples’ are superficially similar to Warhol’s, but his arrangements of seemingly identical items are marked by slight differences and imperfections (Photo: John Janca)

Thiebaud’s “multiples” are superficially similar to Warhol’s, but his arrangements of seemingly identical slices of pies and cakes are marked by slight differences and imperfections: the fruit that bleeds into softening pastry, or a ball of ice cream beginning to melt, comparable to the dying flowers, or spoiling fruit that, in traditional still life painting, serves as a reminder of mortality.

Though Thiebaud draws on his professional expertise in the arrangements of cheeses and sausages, and carefully lettered price cards of Delicatessen Counter (1962), he saw his true artistic lineage in the still lifes of Cézanne and Chardin, and the scenes of modern life typified by the Courtauld Gallery’s own A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), by Manet.

Thiebaud’s artistic coming of age in the 60s – the decade covered by this exhibition – was triggered by a meeting with the artist Willem de Kooning, who urged him to paint what he knew and cared about. But despite the ice-cream colours and innocent pleasures, Thiebaud’s confections do not depict a straightforwardly cheery world.

‘Four Pinball Machines’ (1962). Thiebaud’s hot dogs, pies, pinball machines and deli counters are painted from memory, recalling scenes from his youth that, by the 60s, were already being superseded (Photo: Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries)

‘Four Pinball Machines’ (1962). Thiebaud’s hot dogs, pies, pinball machines and deli counters are painted from memory, recalling scenes from his youth that, by the 60s, were already being superseded (Photo: Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries)

Though familiar, Thiebaud’s hot dogs, pies, pinball machines and deli counters are painted from memory, recalling scenes from his youth that, by the 60s, were already being superseded by prepackaged food and supermarkets.

Melancholy creeps into unexpected places – the empty trays in a display cabinet, the deep shadows that threaten even amped up shop lighting, the absence of a server, or of any human presence. A lonely slice of pie pulls at the heartstrings. There’s even a sausage having an existential crisis in Delicatessen Counter (1963), in which the ghost of a sausage is described in a neutral sweep of a brush through the background colour, there in paint no more or less than its more naturalistically described neighbours.

In Thiebaud’s paintings, scarcity (or at least the end of things as they were) looms over the American Dream, in which lollipops and yo-yos issue forth in an indiscriminate frenzy of production as America faced a new era of crisis and uncertainty.

Against this, Thiebaud offers the reassuring continuity of painting’s “grand tradition”, expressing Cézanne’s geometric fundamentals – “the cylinder, the sphere, the cone” – in candy sticks, yo-yos, and slices of pie on plates.

‘Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life’ is at The Courtauld Gallery, London, until 18 January