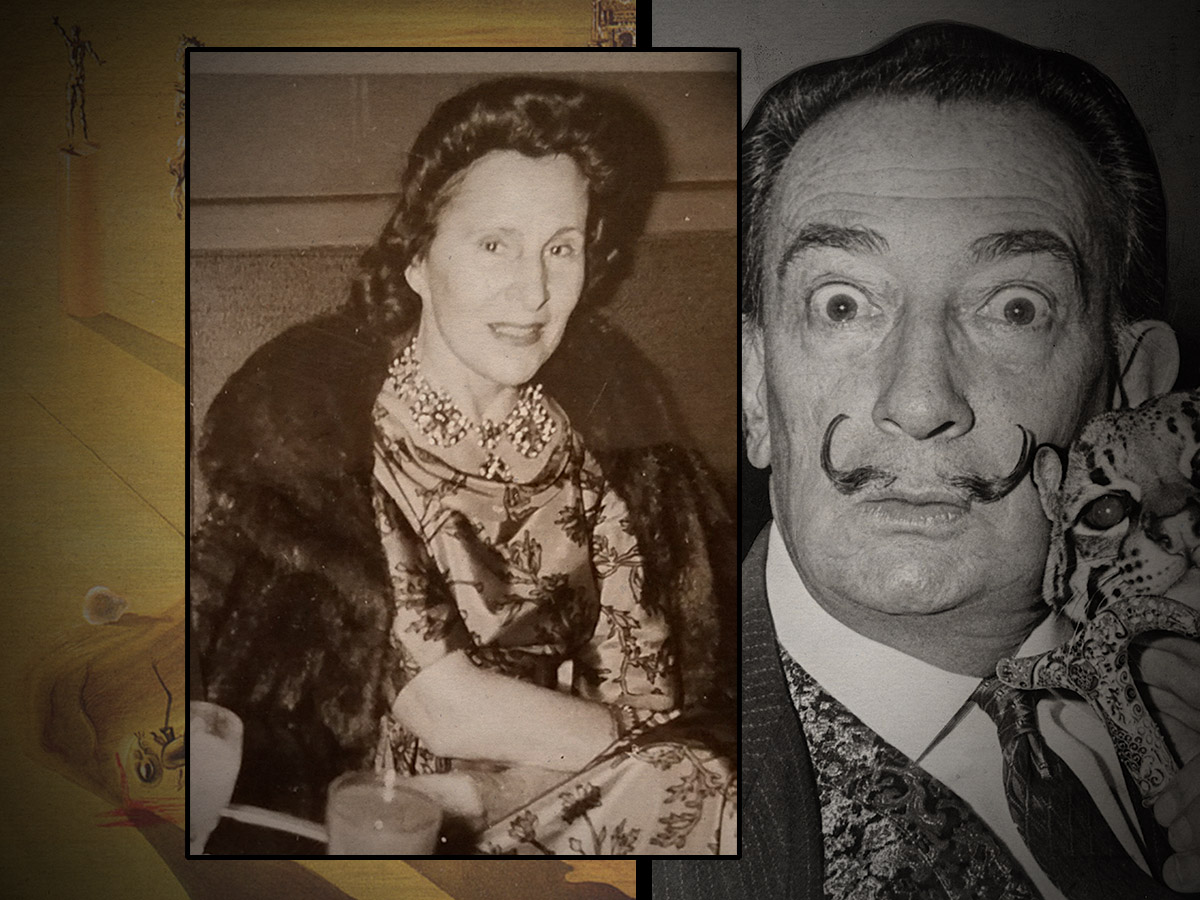

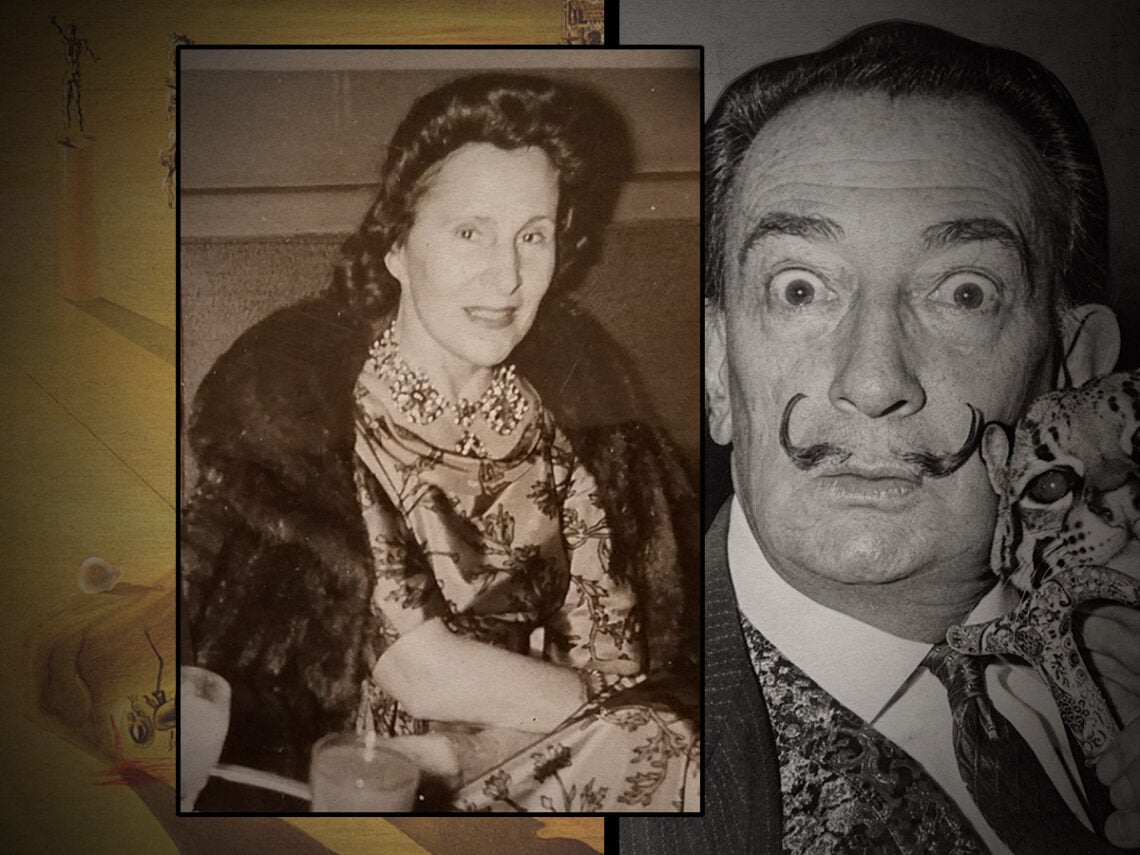

(Credits: Far Out / Fen Labalme / Roger Higgins, World Telegram)

Fri 17 October 2025 9:30, UK

Behind almost every accomplished artist is an equally compelling muse. It’s only fitting, then, that el maestro of the mind’s depths himself, Salvador Dalí, would succumb to another described by many as a ‘monster’.

Most documents about the kind of person Gala Dalí was are enough to leave a bitter taste. More than just a domineering fixture of her own traumas, tragedies, or the external pressures of societal oppression, Gala was, so it would seem, a horrendous person. Her extremities were not ones you’d regard with the kind of earnest pride at witnessing someone stand up to people – it’s the kind you turn your nose up at because it’s so far removed from anything deemed socially acceptable to begin with.

If Gala didn’t like someone, she’d spit at them. If she grew tired of them talking, she’d stub her cigarette out on their arm. In Paris, she was known as a ‘spiteful’ person with demonic tendencies. Luis Buñuel apparently once got so tired of her behaviour that he tried to strangle her. The list goes on – one of Dalí’s dealers, John Richardson, once decorated an entire article with especially colourful language about all the reasons she was the very definition of devil’s spawn.

Some argue that she’s the art world’s most misunderstood muse. But even attempts to clear the mist surrounding her reputation fall flat against the facts, particularly her fixation with fame and money. And so why, then, did impressionable, naive 24-year-old Dalí fall deeply in love at first sight with her, only to have his ardour intensify with the passing of time, throughout his and her lifetimes? Dalí himself claimed Gala was able to sense his genius; she thought him one.

Back then, Gala’s feelings were convincing. She left a life of luxury in Paris with Éluard to be with Dalí in Portlligat. She became his muse in every sense of the word, an object of many of his best works and what some claim to be the making of the artist himself, beyond the passive implications of sitting still as he created his weirdly wonderful surrealist worlds around her. There’s certainly a lot of romance in some of their most famous collaborations, even considering how much Dalí’s success made people grow sceptical of his motivations as an artist and the nature of their relationship as it grew more mythologised.

Gala has been depicted time and time again as this evil, villainous figure who changed Dalí and turned him into a sellout. People physically couldn’t be around her, so they say, because of her temperament and how she spoke to people. Once, before a trip that would leave their pet rabbit home for days, Gala cooked it and fed it to the two of them over lunch, revealing after the fact what she’d done. Dalí was reportedly nauseous at the revelation, but Gala said it was the highest form of cherished love – consuming something she cared about that much.

That’s enough for anybody to assess her character, probably to a good degree of accuracy. But often, as is the case with these haunted figures, overuse of aggressive descriptors aimed at Gala removes any sense of nuance. That doesn’t mean defending any of these choices, of course, but getting to the root of what it all means and why she was that way. We can’t ignore how much of a heavy hand she had in the success of one of the greatest artists in all of history, and if their Púbol Castle is also anything to go by, it also becomes clear just how deprived her life – aesthetically and in the corners of her mind – really was.

Related Topics