This week, Dutch rider Jan-Willem van Schip was disqualified from the Tour of Holland for riding a seatpost with a bend in it. The UCI commissaires deemed it ‘illegal’ and he was unceremoniously booted out of the race. It’s not the first time van Schip – a regular on the six-day scene and a rider prone to pushing the UCI rules around a rider’s position – has been pinged by the tech police, and he’s not alone.

If there’s one thing the Union Cycliste Internationale loves as much as acronyms, it’s an article and regulation. For every watt a rider saves, there seems to be a clause somewhere ready to take it away. From saddle angles to bar widths, how you hold the bars to gear ratios, the UCI’s Technical Regulations are a labyrinth of geometry, millimetres and, occasionally, common sense.

You may like

Jan-Willem van Schip’s backwards seatpost – 2025 Tour of Holland

Few current day riders push the UCI rules with innovation as van Schip does. At this year’s Tour of Holland, UCI officials disqualified him for riding with a seatpost turned the “wrong” way round. The issue? It allegedly breached UCI article 1.3.013, which states that “the saddle shall be positioned such that its foremost point is at least 5 cm behind a vertical line passing through the bottom bracket axle.”

By reversing the seatpost, van Schip had effectively moved the saddle forward of that limit, even though the overall reach and position were similar to his normal fit. His team, Parkhotel Valkenburg, said the bike had previously passed inspection.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Richard Carapaz and the super-tuck – 2021 Liège-Bastogne-Liège

The Ecuadorian climber became the first high-profile victim of the super-tuck ban, during Liège–Bastogne–Liège in 2021. He was filmed descending in the outlawed position whereby a rider sits on the top tube to reduce their frontal area. This position was first used in a high profile event by Matej Mohoric on his way to winning the U23 road race at the 2013 world champs.

The relevant rule, article 2.2.025 bis, forbids any “non-standard position that places the rider’s centre of gravity on any point other than the saddle.” In plain English: you must sit on the saddle, not the top tube. Carapaz crossed the line smiling, only to discover he’d been disqualified for his trouble.

Carapaz’s punishment – handed down just three weeks after the regulation came into force – sent a clear message: the UCI was serious about rider posture, safety and, apparently, aerodynamics.

(Image credit: Shutterstock / Phil O’Connor)

Graeme Obree’s Old Faithful – Hour record and World Championships, 1993–1996

Few riders have forced the UCI’s hand and therefore altered the future of bicycle design quite like amateur Scottish time trialist Graeme Obree. His homemade bike “Old Faithful” was equipped with a set of narrow, straight handlebars that allowed him to adopt the position of a downhill skier. He used bearings from a washing-machine bearings and built it with ultra-narrow-Q-factor cranks.

The bike – voted by the readers of Cycling Weekly as the greatest of all time – helped him smash the hour record in 1993. It was a ride that shocked the world as an unknown amateur beat the record set by the great Francesco Moser. But this tuck position (arms folded under the chest) that upset the rulemakers.

When he turned up to the 1994 World Championships with the same setup, officials banned the position under article 1.3.023, which states that “riders must adopt a position with forearms in line and horizontal when using handlebar extensions.”

Instead of fighting the decision, Obree then invented the “Superman” position (arms stretched forward) only for that to be banned too.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

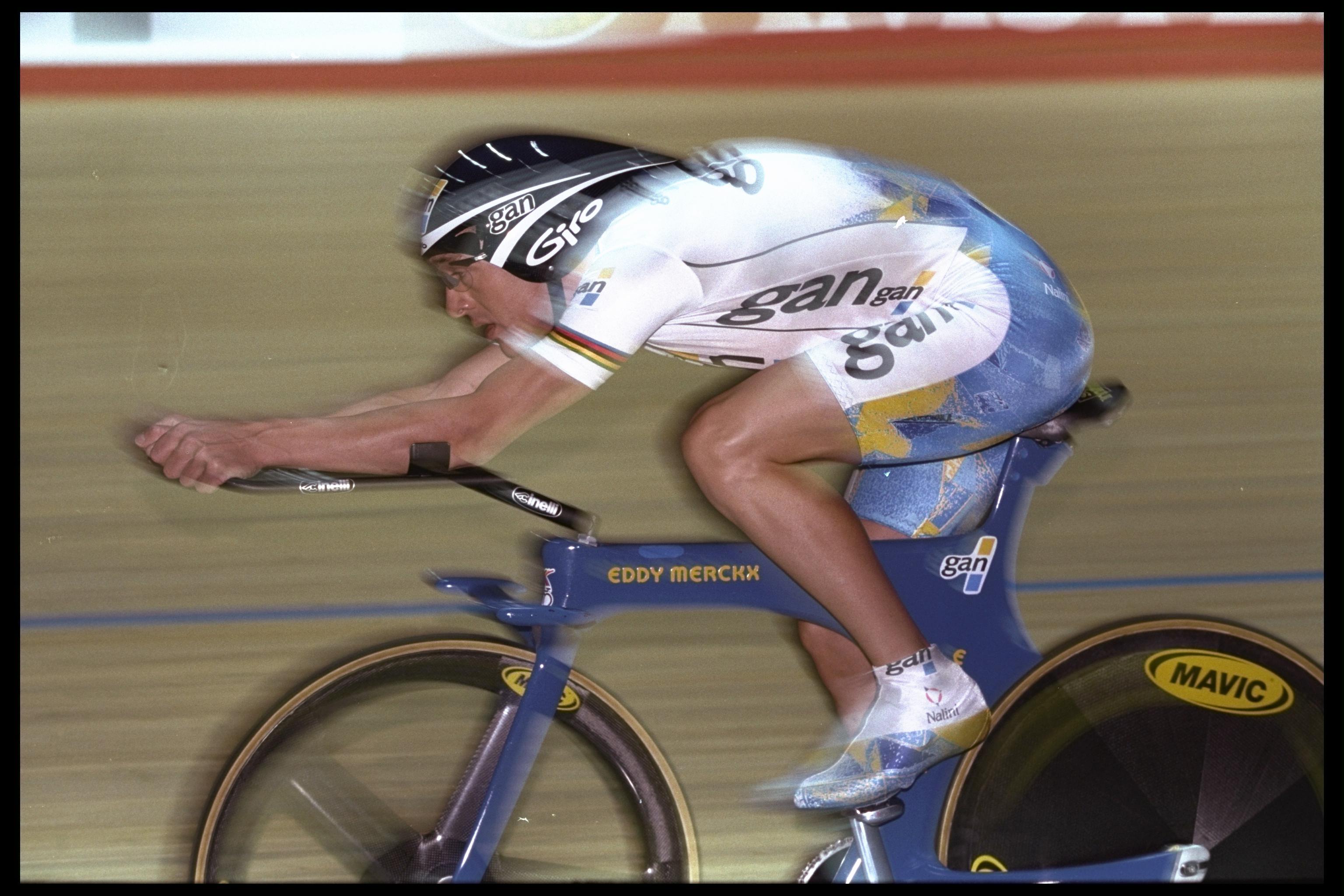

Chris Boardman, the Superman position and monocoque bikes – 1996 Hour Record

While Obree innovated in his garage, his great British TTing rival Chris Boardman had the might of Lotus Engineering behind him. His Lotus 110 superbike and Obree-invented-Superman position were so efficient that the UCI, spooked by speeds edging into the unimaginable, rewrote the hour record regulations entirely and came up with the Lugano charter aimed to prevent an aero arms race and put the rider rather than machine at the centre of the sport. This provided the ethos behind technical regulations.

The governing body later introduced article 3.6.001, stipulating that attempts must use “traditional” frames modelled on Eddy Merckx’s 1972 record, effectively banning monocoque carbon frames, integrated bars and extreme aero positions.

Boardman’s 1996 record still stands in the “Best Human Effort” category, but the new rule forced everyone else back to steel tubing and drop bars. If imitation is flattery, rewriting the law must be the sincerest form of compliment.

After interest in the hour record dropped off, the rules were updated again in 2014 allowing riders to use then modern aero positions and equipment. Jens Voigt took advantage and set the record in Grenchen Switzerland then immediately retired.

Jan-Willem van Schip (again) – 2021 Baloise Belgium Tour

Back in 2021, the 6’4” tall Dutchman was booted out of the Baloise Belgium Tour for using a pair of custom Speeco Aero Breakaway handlebars that let him rest his forearms on the tops. The commissaires cited article 2.2.025: riders must “keep at least one hand on the handlebars at all times and may not adopt a position resting the forearms on the handlebar unless competing in a time trial.”

It was part of a wider UCI crackdown that also outlawed the so-called super-tuck – the downhill position where riders perch on the top tube for better aerodynamics. Van Schip defended his setup as a safety measure and an ergonomic innovation, but the commissaires were unmoved. He was told to pack his bags.

Floating little-fingers – 2021 position purge

In early 2021 the UCI launched what became known as the “position purge”, updating article 1.3.008 to cover every imaginable riding posture. Alongside the super-tuck ban came new clauses stating that riders must have “hands and at least one finger wrapped around the handlebars at all times”.

That meant no more showboating down descents with fingertips hooked over the hoods or resting palms on the tops. Commissaires were told to penalise anyone failing to comply. Several WorldTour riders, including some in the UAE Tour and Paris–Nice that spring, received warnings or fines for the offence.

The same update also reinforced the saddle-use clause, stating that “riders must maintain contact with the saddle at all times except during obvious efforts such as climbing or sprinting.” In other words, no sitting on the top tube.

Most riders shrugged and adjusted, but it gave the internet a month of memes featuring commissaires with protractors and laser levels.

The great saddle-angle clampdown – 2011 Tour de France

A special mention goes to the commissaires at the 2011 Tour de France, who embarked on an early-morning crusade to check saddle angles. Under article 1.3.014, saddles must be “essentially horizontal, with a maximum deviation of 9deg.” Officials armed with spirit levels swarmed team buses, ordering mechanics to tilt seats up (or down) before the start.

No-one was disqualified, but the sight of world-class riders getting their saddles measured like schoolboys at a uniform inspection was a reminder that in cycling, nothing escapes scrutiny, not even a few degrees of tilt.

Femke Van den Driessche’s hidden motor – 2016 Cyclo-cross Worlds

Some infractions are minor; others make history. In January 2016, Belgian under-23 rider Femke Van den Driessche became the first and only rider to be caught for technological fraud. Officials at the Cyclo-cross World Championships discovered a concealed motor and battery inside her spare bike’s seat tube.

Under article 1.3.010, any “propulsion assistance other than solely by the rider’s legs is prohibited.” The UCI imposed a six-year ban backdated to 2015 and stripped her of results. Van den Driessche claimed the bike wasn’t hers, but the damage was done. It was cycling’s first confirmed case of so-called “mechanical doping” and changed how equipment was checked forever.

Honourable mention, Dan Bigham and the KGF track squad

Although not actually banned for any of the team’s innovations, the UCI introduced specific regulations to standardise aerodynamic equipment in response to creations from Wattshop, Dan Bigham’s aero kit company.

The UCI’s new rules meant armrests were limited to a maximum length of 125mm, a maximum inclination of 15 degrees, and each armrest must be separate. Additionally, extensions must not exceed 40x40mm in cross-sectional area. My personal favourite though, measuring the arm rest pads from the centre to the tip of the extension, and use of compressing foam.

KGF used longer arm rests and stacked low density foam to initially get around the height restriction and measurement rules while complying to the rules, the UCI swiftly intervened.

These changes aimed to prevent excessive hand elevation and ensure fair competition. Subsequent updates to the UCI regulations addressed these concerns, leading to the current standards in place now.

The rules also resulted in the hilarious sight of a Commissaire telling Dan Bigham he couldn’t ride with a product because it wasn’t ‘commercially available’ . Bigham went off to get a tablet, opened the Wattshop website and showed the commissaire exactly how much it could be bought for.

The team went on to win a Team Pursuit at a World Cup, only for the UCI to change the rules so that only national teams could compete.

(Image credit: Supplied by Dan Bigham)

A tradition of innovation

From hidden motors to reversed seatposts, each of these cases tells a story about cycling’s uneasy relationship with innovation. The UCI’s rules are designed to keep competition fair and safe, but they also set boundaries that inventive riders will always test.

Jan-Willem van Schip might feel unlucky to have been singled out, but he’s merely the latest in a long line of riders who discovered that, when it comes to tech, the commissaires always have the final say.

The sport needs its mavericks, they make the rest of us look twice at what’s possible. But as van Schip now knows, creativity in cycling is only legal until the rulebook catches up.